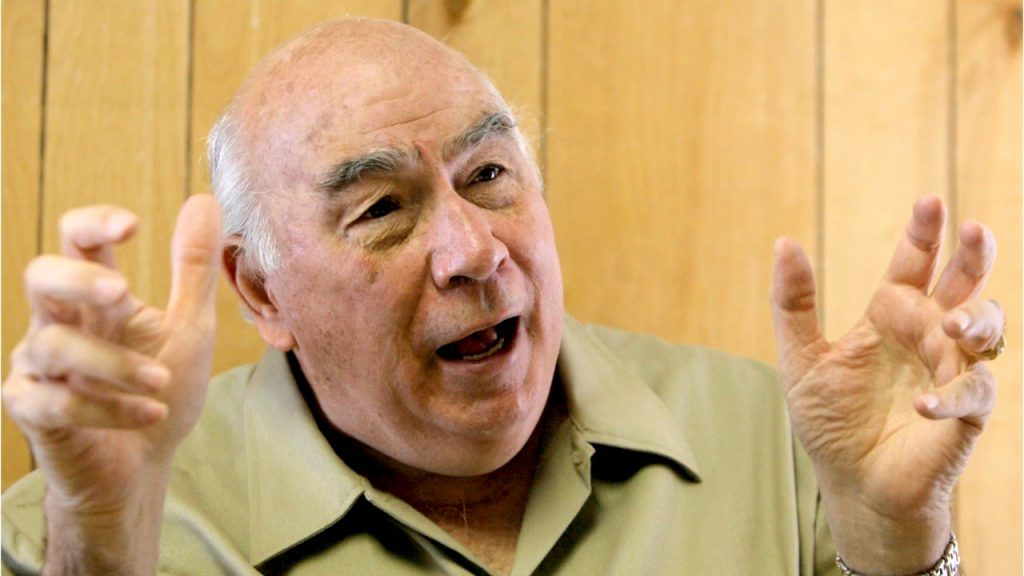

Robert Murray, outspoken coal miner who battled EPA, dies at 80

Robert Murray, a fourth-generation coal miner who became one of the embattled industry’s most outspoken advocates, has died. He was 80.

Murray died early Sunday morning at his home in St. Clairsville, Ohio, of a lung disorder, according to Michael Shaheen, the family’s lawyer. He was diagnosed in 2016 with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, or black lung disease, and had been known to attend industry events with a portable oxygen container.

A native of Ohio coal country, Murray joined a mining company at 17 to help support his family. He rose through the ranks to become chief executive officer of North American Coal, but was fired in 1987 after resisting an effort to trim the company’s obligations to retirees. The following year he founded Ohio-based Murray Energy, which grew into the largest closely held US coal producer but was eventually driven into bankruptcy as demand for the fuel waned.

During Murray’s lifetime, coal shifted from the most important source of US electricity to the most vilified driver of climate change. The highly litigious Murray emerged as one of the industry’s leading voices against government regulation during Barack Obama’s Presidency as the government stepped up efforts to restrict coal-fired power plants, which have declined by more than half since 2010.

On October 19, Murray announced he was stepping down as chairman of ACNR Holdings, the restructured company that last month emerged from bankruptcy almost a year after Murray Energy filed for Chapter 11.

His death comes shortly before a US presidential election that’s likely to have a significant impact on the industry. President Donald Trump has rolled back numerous environmental policies in an effort to prop up coal demand, but he’s had little success. Joe Biden, the Democratic candidate who’s leading in the polls, has called for moving to a green electrical system by 2035, a goal that would leave little room for coal-burning power plants.

Coal in veins

Murray’s father was a coal miner, and so were his grandfather and great-grandfather. His three sons worked for the company that bore their name. With all that coal in his veins, Murray had only contempt for “environmental alarmists” who sought to restrict the fuel that sustained his entire family.

Murray dismissed the landmark 2015 Paris climate agreement as “a meaningless fraud that will have no effect on carbon dioxide emissions.” Years earlier, he called acid rain a hoax. Murray later emerged as a vocal supporter of Donald Trump, cheering the president’s efforts to roll back environmental policies. For Murray, coal was always the solution, never the issue.

“There’s more of an energy problem in America than there is an environmental problem,” he said in early 2018.

Robert Edward Murray was born January 13, 1940, in Martins Ferry, Ohio. When he was 9, his father was paralyzed from the neck down in a mining accident. His mother later contracted breast cancer. By the time he was 12, Murray was mowing lawns to help support the family, sometimes strapping on a miner’s head lamp to keep going after dark.

Underage miner

Murray started working for a mining company in his late teens. He graduated from Bethesda High School as valedictorian and turned down an offer from the local Rotary Club, which wanted to send him to medical school if he would agree to return and become the town doctor.

Instead, he beat out 300 students to win a $6 500 scholarship from North American Coal to study mine engineering at Ohio State University. He later joined the company and was overseeing 7 000 workers by the time he was 30. Having started his career at the bottom, Murray remained close to the miners and as CEO he pushed back when the company was planning a reorganization that would have let it trim its obligations to 1,800 United Mine Workers of America pensioners. In October 1987, after 31 years with the company, he was fired. North American Coal has said it changed CEOs as part of a broader strategy to diversify into non-coal operations.

Forms company

During his tenure, Murray had overseen the building of the Powhatan No. 6 mine in eastern Ohio. In 1988, he bought it to form his own company, mortgaging almost everything he owned and lining up about $66.5-million in financing. From that single mine, he expanded Murray Energy to become the fourth biggest US coal producer in 2018, with 13 active mines in five states, though Powhatan No. 6, the one that started it all, closed in 2016, finally tapped out.

“Bob Murray was a force in the mining industry whose dedication to coal was unrivaled,” Rich Nolan, CEO of the National Mining Association trade group, said in an emailed statement. “All who knew him would agree — there was no one more passionate about the importance and value of coal.”

From the start, Murray’s politics were a key part of his business strategy. He railed against environmental efforts, calling measures to bolster the Clean Air Act in 1990 a “criminal fraud”. He later filed at least a dozen lawsuits against the government seeking to block Obama’s landmark climate policy, the Clean Power Plan.

In recent years, utilities have increasingly shifted away from coal in favor of cheap natural gas and renewables. That’s spurred numerous bankruptcies by miners, including Murray Energy, which filed for Chapter 11 protection in October 2019 after he unsuccessfully pressed the Trump administration to help the industry.

Murray’s politics sometimes led to conflict for the company. Employees have alleged that he pressured them to support his favored candidates, including requesting that they attend fundraisers and make contributions, according to a 2014 lawsuit filed by a worker who said she was fired for refusing to do so. The suit was settled in 2015.

Safety record

Murray Energy has also been criticized for its safety record, notably after its Crandall Canyon mine collapsed in 2007, leaving six miners and three rescue workers dead. The Utah mine had previously been cited for violating federal regulations, and government investigators later concluded the cave-in was due to the company’s practices. Murray, however, has repeatedly said the incident was caused by an earthquake, a claim that’s been widely refuted.

Murray has repeatedly turned to the courts over that assertion. He sued the New York Times in 2017 for libel, disputing the newspaper’s claim that he had lied about the cause of the Crandall Canyon disaster. And later that year he filed suit against the television network HBO and the comedian John Oliver for defamation. At issue was a segment by Oliver that pilloried the executive for his politics and his treatment of employees, including his comments about an earthquake triggering the Crandall Canyon collapse. He later dropped the suit against the New York Times, and a judge dismissed the Oliver case citing First Amendment issues.

Murray married the former Brenda Lou Moore and had three children: Robert, Ryan and Jonathan.

(By Will Wade and Tim Loh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments