Rising credit risks pose huge challenge for the worst polluters

Credit risks keep creeping higher for the world’s biggest polluters.

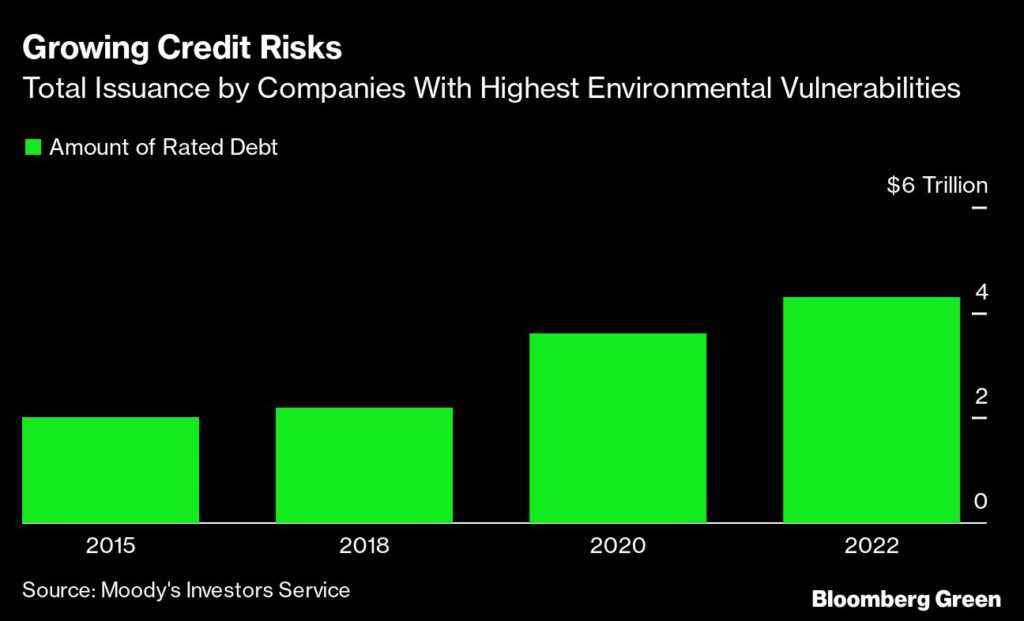

In fact, the companies facing perhaps the largest climate crisis-related losses have more than twice as much rated debt as they did when the Paris Agreement was announced almost seven years ago, according to an analysis by Moody’s Investors Service.

To be more specific, the 16 industries considered to have “very high” or “high” environmental credit risks have about $4.3 trillion of rated debt (roughly equal to Germany’s gross domestic product), up from $2 trillion in November 2015, Moody’s reported. That equals about 5.1% of total debt outstanding, up from 3% in 2015.

Whether this upward trend continues “largely depends upon the direction of environmental regulations, policy and corporate actions,” said Ram Sri-Saravanapavaan, senior analyst and lead author of the report.

The numbers are consistent with the amount of funds that banks have served up for fossil-fuel producers via bond sales and loans. Since the start of 2016, banks have arranged about $4.5 trillion of financing for oil, gas and coal companies, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Companies most susceptible to credit risks are those involved in the coal, chemicals, mining, and oil and gas industries, according to Moody’s. To put that in perspective, only coal mining and coal terminal operators were seen by the firm’s analysts as having “very high” environmental credit risks as recently as 2020.

The growing credit hazards are another sign of the huge global pressures that are building to address the warming planet. And the recently concluded United Nations climate summit in Egypt did little to reduce those concerns as national leaders focused on implementing existing, unfulfilled commitments — rather than adopting stricter global emissions targets.

“Aside from a broadly worded agreement to establish a loss and damage fund for poor countries most vulnerable to climate change, there was a lack of new major pledges,” the Moody’s analysts wrote after the COP27 ended.

For corporations, the realities have only worsened. Climate-related risks are increasing and companies that lack credible net-zero emissions plans will likely see their capital costs rise and demand for their goods and services decline.

Moody’s said the environmental categories considered most material to credit quality center around how companies are making the carbon transition and handling issues related to physical climate risks, water management, natural capital, and waste and pollution.

Analysts assign the “very high” risk label to sectors where the credit impact of environmental risks is already visible or likely to emerge soon, and also to issuers that have limited scope to manage these risks without making major structural, financial and policy adjustments in the near term.

According to Moody’s, three oil and gas sectors, as well as the chemicals, metals and mining groups, moved to “very high” risk this year from “high” risk in 2020. Integrated oil and gas companies, for example, will require substantial investment over the next several years to adapt their business models and transition a low-carbon economy.

For the chemicals industry, many of the companies use or create toxic feedstocks, intermediates and other hazardous materials during the production process. This leaves them vulnerable to legal liabilities and rising expenses from increasingly stringent regulators, Moody’s reported.

All of the data show “that environmental considerations are increasingly pressuring issuers’ credit profiles and will continue to do so,” Sri-Saravanapavaan said.

(By Tim Quinson)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments