Rich nations scramble to seal coal transition deals before COP27

As they prepare for the next round of global climate talks in November, officials from rich countries are trying to pull together a series of multibillion-dollar packages to help poor countries phase out coal.

But negotiations have been snarled by national politics and Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has made the dirtiest fossil fuel a lucrative commodity to mine and export, according to people familiar with the talks who asked not to be identified because the discussions are private.

The talks stem from a landmark $8.5 billion pledge by the UK, US and European Union before last year’s COP26 summit to support South Africa’s move away from fossil fuels. The deal has become a model for decarbonizing other nations including India, Indonesia and Vietnam. The hope is that agreements can be reached with those countries before COP27, the people said, and that details of the South Africa pact will be finalized by then.

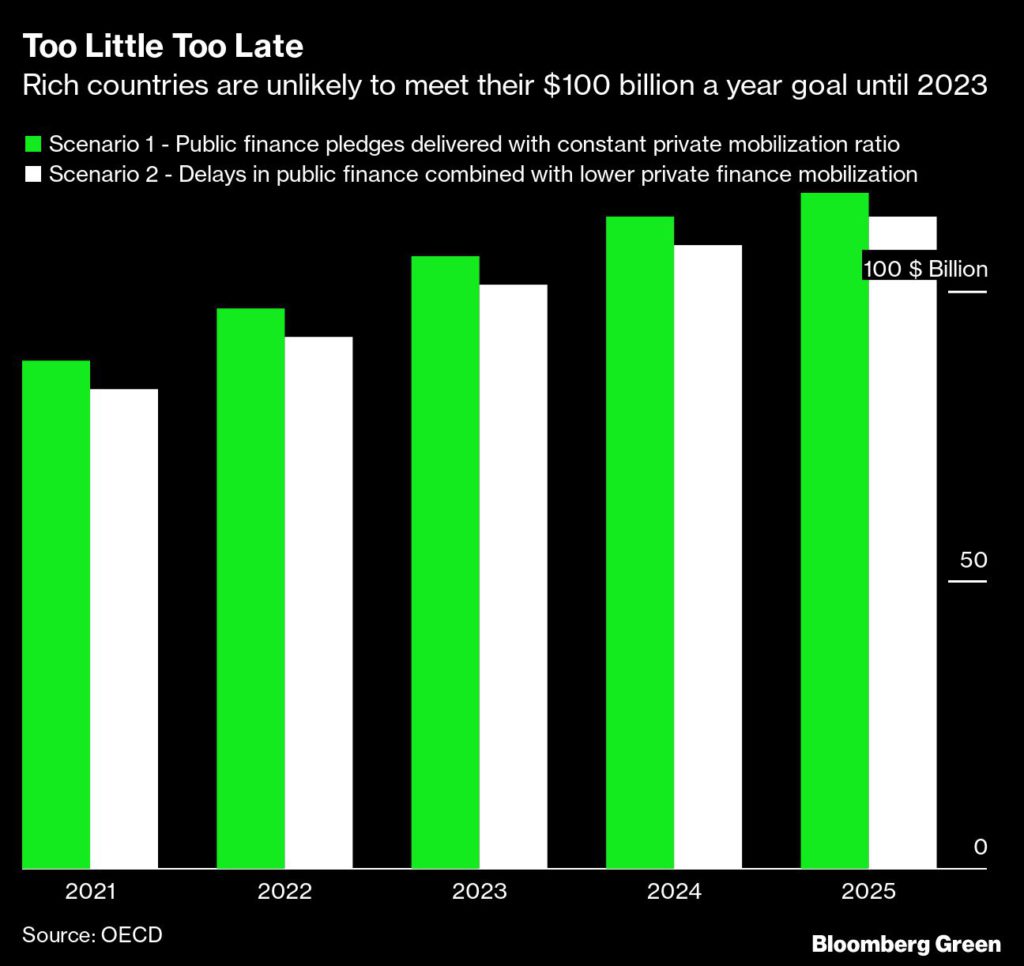

Much of the focus is on Indonesia, which will this year host the Group of 20’s meetings and have significant influence over COP27. Getting a deal done could earn rich countries some goodwill in Egypt after they failed again last year to meet a decade-old target to deliver $100 billion a year in climate finance for poor nations. But developed countries are also adamant that money can only flow if recipient governments come up with detailed economy-wide plans to end the use of coal.

Three officials from donor countries that visited Indonesia this year raised concerns privately that President Joko Widodo’s cabinet remains split over the need to end the use of coal. That’s been compounded by the war, which has raised the demand for coal exports. The government hasn’t come up with a coherent plan to transition away from coal, an obstacle to any breakthroughs this year, they said, asking not to be named so as not to jeopardize the talks.

“There are about 20 different visions within the Indonesian government about what they’re actually talking about,” said Jake Schmidt, senior strategic director of the international climate program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, who closely monitors the discussions. “There are still factions within the Indonesian government that are wondering why should we not build more coal and why should we transition?”

Indonesian ministries contacted by Bloomberg didn’t immediately respond to queries sent ahead of a week-long public holiday. The government last October released a plan to get to net-zero emissions by 2060 which includes retiring all coal-fired power plants by 2055.

Indonesia’s finance minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, has said one of the biggest challenges is convincing private owners of coal plants to switch them off. Speaking on the sidelines of the IMF spring meetings in Washington in April, she also said rising inflation and borrowing costs were making any deal tougher to reach.

“If you ask Indonesia to transition off this energy that will bankrupt my budget, bankrupt the PLN, it will not fly,’’ she said, referring to the state electricity utility PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara.

Still, progress has been made recently as officials engaged in difficult questions about the speed of Indonesia’s energy transition and discussions have become more granular, according to a U.S. Treasury official familiar with the matter. US officials met with ministers and PLN representatives in Washington last week.

Meanwhile talks between India and the U.S. and Germany — representing the EU — haven’t progressed significantly, according to people familiar with the discussions. Any commitment could end up being a bilateral arrangement rather than a multilateral one, two of the people said. A coal shortage that’s led to power cuts are a hurdle, one of the people said. The Indian government has also chafed at being “talked down to” by Western countries that have offered more studies than concrete solutions, another person said. India’s foreign ministry didn’t respond to questions.

As for the South Africa deal, major elements of the financial package are still being developed six months after the agreement was signed. Finer points about how the money will be spent have yet to be confirmed, including how much will go to heavily indebted utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd., how communities will be compensated and how any loans will be structured.

Technical details are now being worked out to determine the contours and scale of financing, with one goal being that it enables the government to escape long-term pressure tied to Eskom’s debt, a U.S. Treasury official said. When the deal was announced last year, South Africa hadn’t designated a lead negotiator and Eskom’s participation was unclear, among the many steps needed to turn the declaration into a final plan, the official said.

The country has since appointed Daniel Mminele, a former South African central banker, to lead the talks. He said that “work is progressing well” and the focus over the next few weeks will be on “assessing the detail of the funding elements relative to South Africa’s needs and priorities.”

Though there is still a chance that a broad agreement in principle will be reached for Indonesia before the G-20 meeting in Bali in November, some activists and insiders are more optimistic about the prospects for a pact with Vietnam at this point. The country has a smaller coal industry and more potential for wind energy, one person said. Officials with Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade were unavailable for comment.

The European Commission confirmed it is exploring energy transition partnerships with Vietnam, India and Indonesia. “A first progress review will be conducted before the summer, in good time before COP27,” a spokesperson said.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry said work was underway on Indonesia and the South Africa talks were moving forward. “We’ve mobilized some funding to help deal with Eskom — bail out the Eskom problem of South Africa and be able to help them transition,” he said at the Global Electrification Forum hosted by the Edison Electric Institute on April 25. “In Indonesia, they don’t have an Eskom problem, but they do have sort of a break-the-status-quo” challenge, he said.

Negotiations are ongoing at high levels. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has met with finance ministers from South Africa and Indonesia, a sign of the seriousness of the effort, which might otherwise be the domain for energy and environmental ministers.

The outcome of the talks will have significant consequences for the success of COP27. Striking deals with larger developing countries could lead to similar arrangements to help smaller and more climate-vulnerable nations.

The South Africa plan “provides a good model to build on here,” said Brendan Guy, lead strategist with NRDC’s international climate program. “But the question really is, can similar packages be tailored for the unique needs of countries like India, Indonesia, Vietnam and others to really help them accelerate the move past coal?”

(By Jess Shankleman, Jennifer A Dlouhy and Archana Chaudhary, with assistance from Antony Sguazzin, John Ainger, Yudith Ho, Eko Listiyorini, John Boudreau and Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments