Rich nations may fork out billions to wean Indonesia off coal

Ever since Indonesia accelerated plans last year to achieve carbon neutrality, a parade of climate envoys from developed nations has headed to the archipelago, offering assistance and financial aid in exchange for a commitment by the world’s biggest exporter of coal by weight to phase out coal power.

Officials from the U.S. and Europe hope to secure a deal by the time Indonesia hosts G-20 leaders in Bali in November, establishing a major milestone in the global effort to cut emissions and providing an impetus for the United Nations’ COP27 climate summit in Egypt the same month.

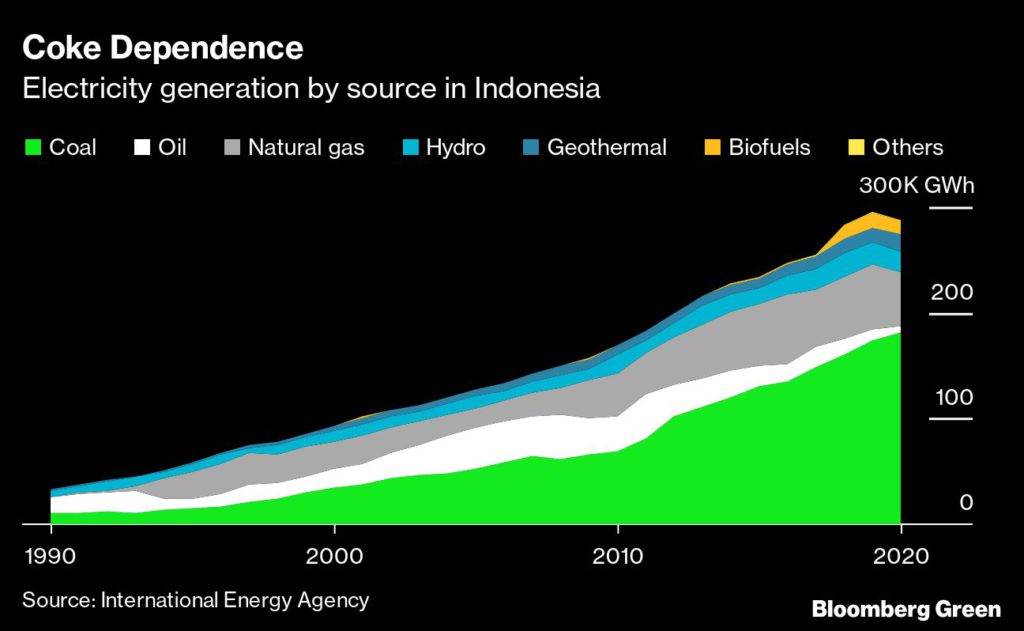

It’s an ambitious goal. Coal generates about 60% of Indonesia’s electricity and the fossil fuel has made fortunes for some of the nation’s most powerful business elites. The war in Ukraine has lifted global demand, boosting the stocks and profits of coal-mining companies, making them even more attractive for investors. Meanwhile, the nation’s monopoly power distributor gets coal for its power plants at a discount, giving it little incentive to hook up renewable-energy suppliers.

Rich nations are betting that agreements known as Just Energy Transition Partnerships will help break the deadlock and provide fossil fuel-dependent nations such as South Africa and Indonesia with the financing and support to speed up the transition. Donors must “break the status quo,” said U.S. climate envoy John Kerry in April.

Yet three people from donor countries with knowledge of the talks, who visited Indonesia this year, raised concerns privately that Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s cabinet is split over the need to end the use of coal. Some want to continue building the coal sector, negotiators said. Others are seeking billions for each shuttered coal plant and some factions would like to continue building them, said Jake Schmidt, senior strategic director of the international climate program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, who monitors the discussions.

“That’s not what the donor countries” envision, Schmidt said. “The framework is basically stop building new coal and begin to decline,” but “there are parts of the Indonesian government that are not quite there.”

Publicly, the Indonesian government has made a strong commitment to rein in coal and develop green energy. Dian Triansyah Djani, Co-Sherpa for Indonesia’s G20 presidency and ambassador to the UN, said the country welcomes the discussions toward the Just Energy Transition Partnership. Jokowi, as the president is known, has pledged to shut all Indonesia’s coal-power plants by 2055 and be 100% dependent on renewable sources five years later. No new coal-fired power plants will be approved and there are plans to finally roll out a carbon tax in July.

Those targets will be tough to meet without a deal with wealthy nations, as well as detailed regulations that force power users and generators to switch to clean energy. A government study said the nation will need $150-$200 billion investment in low carbon programs annually until 2030, or roughly 3.5% of GDP, to meet its net-zero targets.

“If they don’t have a comprehensive dialogue and a comprehensive strategy, it’s unlikely that the transition will happen,” said Stephan Garnier, Indonesia energy coordinator and lead energy specialist at the World Bank.

Indonesia is one of a handful of resource-driven nations that could make a major difference in the battle to curb climate change. Southeast Asia’s biggest economy has the world’s fourth biggest population and is the second-biggest coal producer. Coal output began to soar in the 1990s and powerful local investors snapped up controlling interests in some mining companies, augmenting the wealth of a largely decentralized elite class. Predicting a boom in demand for electricity, Indonesia began to invest heavily in coal power, a trend that continued under Jokowi.

In 2015, he launched a program to build 35,000 megawatts of new power capacity largely supported by an additional 117 new coal-fired power plants. By 2020, electricity output had grown more than five-fold over nearly two decades.

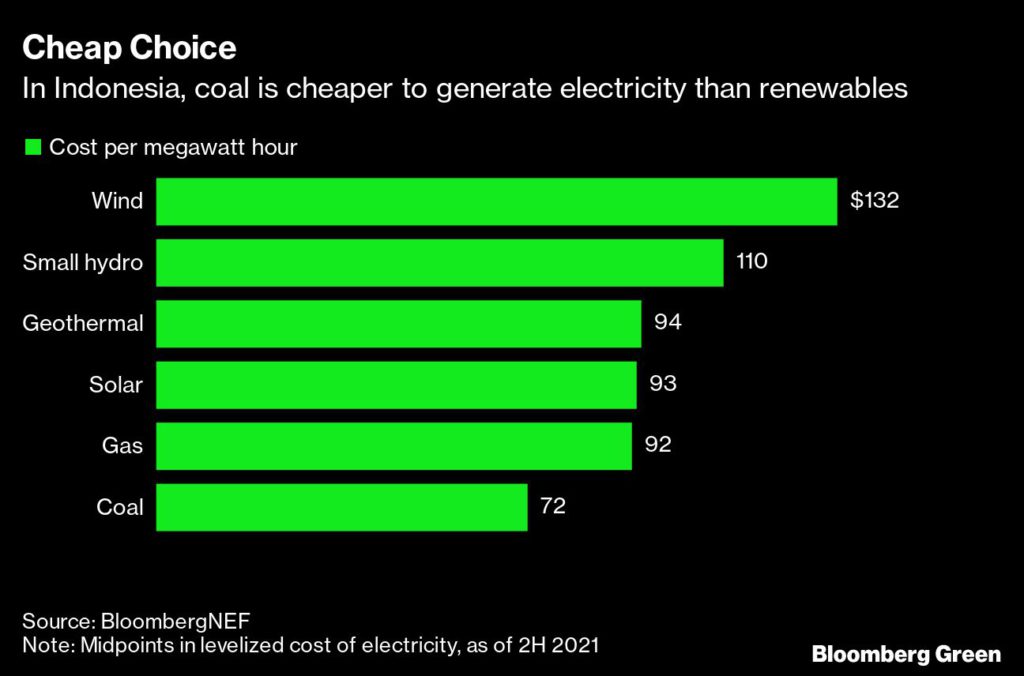

But growth in demand didn’t keep up. When the added capacity comes online, and some of it is years behind schedule, it could create a power surplus of as much as 40%, according to the Institute for Essential Services Reform. The country’s biggest grid, covering Java and Bali, already has 24% more capacity than it needs, according to BloombergNEF. That has driven domestic coal power costs well below international market rates, squeezing out renewables.

The nation’s 2030 goal is to reduce emissions by between 29% and 41%. Officials have said the country can reach the low end of the band with measures such as mixing plant debris in with coal, retiring older power stations early and reducing subsidies, but it will need foreign assistance to achieve more.

“Because of this oversupply of coal, going beyond that by 2030 will be difficult,” said Garnier.

Much could depend on talks between donors and South Africa, which has led the field in terms of establishing a JETP. Ambassador Djani said Indonesia is in talks with South Africa about the structure and implementation of the partnership.

But even if all goes well in South Africa, Indonesia has its own set of unique issues to overcome. The government requires coal miners to sell at least a quarter of their supplies domestically with prices capped at $70 a ton for the highest quality, compared with recent prices of around $400 a ton in the global market. That means state utility PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara can produce electricity from its power plants more cheaply than the cost of producing green power. Worse still, PLN signed take-or-pay contracts with the coal plants, many of which operate well below capacity. So when demand increases, PLN can draw more power from them at zero extra cost, which is tough to beat, no matter how cheap solar is.

Investments in clean energy “must follow PLN’s timeframe and needs, with no other recourse if a deal with PLN doesn’t work out,” said Fabby Tumiwa, executive director at the Jakarta-based Institute for Essential Services Reform. “A reform to the electricity market structure so that PLN is not the single off-taker would quicken the shift to renewables.”

And coal remains the heart of Indonesia’s energy supply, with production at record levels. Even with the moratorium on new projects, coal-fired power plants already under construction will add another 14 GW of capacity from 2021-2030. This year, Jokowi broke ground on the nation’s first coal gasification plant, which will cost $2.3 billion.

In coal-mining regions such as East Kalimantan, proposed site of Indonesia’s new capital, coal accounts for almost half the economy, according to Tumiwa at the IESR. Increased demand from abroad since the war in Ukraine has sent shares in mining companies soaring. Shares of miner PT Adaro Minerals Indonesia have jumped more than 1,500% since its public debut in January. As many as half of the 575 lawmakers in parliament have connections with the mining sector, according to the Indonesia Mining Advocacy Network, which investigates the crossover between officials and business.

“Countries have always relied on the resources available to them to increase electrification rates and drive economic growth,” said Caroline Chua, an analyst with BloombergNEF. “In Indonesia, that resource was coal.”

Indonesia has the theoretical potential to meet the entire world’s electricity demand from renewables, according to an IESR study last year, but it has fewer solar panels than Norway and has barely begun to tap abundant wind and geothermal resources. Lifetime costs of solar projects in Indonesia could be as much as 40% lower if finance and investment risks were comparable to those in advanced economies, according to the International Energy Agency.

Still, there are some signs of progress. The Asian Development Bank last year launched a multi-billion dollar plan that aims to help Indonesia and the Philippines retire 50% of their coal plants over the next 10 to 15 years. Indonesia, in turn, has said it will retire some of the power stations earlier than scheduled if they meet the end of their economic life-cycle, a plan Tumiwa says could involve as much as 9.3 gigawatts of capacity through 2030.

And despite all the obstacles, negotiators are optimistic that a deal can be reached this year.

“Indonesia will be our next partnership,” US Treasury Climate Counselor John Morton said at an event with the Center for Global Development in early May. “If this were easy, it would have been done years ago. Countries could have managed this on their own,” he said. “We’re talking about economy-wide economic transitions of energy sectors, which are huge political beasts.”

(By Philip Heijmans and Dan Murtaugh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments