Putin is betting coal still has a future

European governments are drawing up plans to phase out coal, U.S. coal-fired power plants are being shuttered as prices of clean energy plummet, and new Asian projects are being scrapped as lenders back away from the dirtiest fossil fuel.

And Russia? President Vladimir Putin’s government is spending more than $10 billion on railroad upgrades that will help boost exports of the commodity. Authorities will use prisoners to help speed the work, reviving a reviled Soviet-era tradition.

The project to modernize and expand railroads that run to Russia’s Far Eastern ports is part of a broader push to make the nation among the last standing in fossil fuel exports as other countries switch to greener alternatives. The government is betting that coal consumption will continue to rise in big Asian markets like China even as it dries up elsewhere.

“It’s realistic to expect Asian demand for imported coal to increase if conditions are right,” said Evgeniy Bragin, Deputy Chief Executive Officer at UMMC Holding, which owns a coal company in western Siberia’s Kuzbass region. “We need to keep developing and expanding the rail infrastructure so that we have the opportunity to export coal.’’

The latest 720 billion ruble ($9.8 billion) project to expand Russia’s two longest railroads — the Tsarist-era Trans-Siberian and Soviet Baikal-Amur Mainline that link western Russia with the Pacific Ocean— will aim to boost cargo capacity for coal and other goods to 182 million tons a year by 2024. Capacity already more than doubled to 144 million tons under a 520 billion ruble modernization plan that began in 2013. Putin urged faster progress on the next leg at a meeting with coal miners in March.

“Russia is trying to monetize its coal reserves fast enough that coal will contribute to GDP rather than being stuck in the ground,” said Madina Khrustaleva, an analyst who specializes in the region for TS Lombard in London.

Putin is betting that his country’s land border with China and good relations with President Xi Jinping make it a natural candidate to dominate exports to the nation that consumes more than half of the world’s coal. His case is helped by the fact that Australia, currently the number one coal exporter, is facing trade restrictions from China amid a diplomatic dispute over the origins of the coronavirus.

But the plan is fraught with risk, both for Russia’s economy and the planet. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recommends immediate phasing out of coal to avoid catastrophic global warming and the effects of climate change are expected to cost Russia billions in coming decades.

Earlier this month the International Energy Agency went one step further and said no new fossil-fuel infrastructure should be built if the world wants to keep global warming well below 1.5 degrees Celsius. With all but one of the top 10 economies committed to reaching net-zero emissions within decades, the IEA’s Net-Zero by 2050 Roadmap calls for phasing out all coal power plants without carbon capture as soon as 2040.

It’s also not a given that Asian coal demand will keep growing. Coal consumption in China is poised to reach a record this year and the country continues to build coal-fired power plants, but it also plans to start reducing consumption starting in 2026. At the same time, it’s increasing output from domestic mines, leaving less room for foreign supplies. Even in the IEA’s least climate-friendly scenarios, global coal demand is expected to stay flat in 2040 compared to 2019.

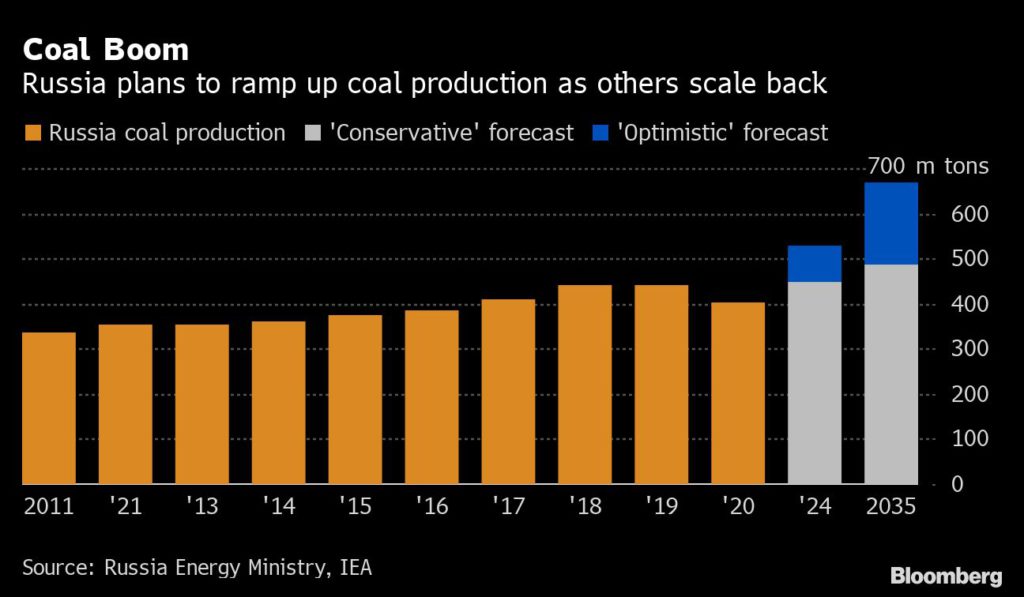

A coal strategy approved by the Russian government last year envisages a 10% increase in coal output from pre-pandemic levels by 2035 under the most conservative scenario, based on rising demand not just from China, but also India, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and possibly Indonesia.

The relatively low sulphur content of Russian coal might give it an edge in Korea, which has tightened pollution laws in recent years, but other Asian countries have struggled to secure funding for proposed plants and Indonesia said this week it won’t approve any new coal-fired power plants. At a Group of Seven nations meeting, environment ministers agreed to phase out support for building coal power plants without carbon capture before the end of this year.

A coal strategy approved by the Russian government last year envisages a 10% increase in coal output from pre-pandemic levels by 2035

For Putin there is more at stake than just money. At a video conference in March, he reminded government officials that the coal industry drives the local economies of several Russian regions that are home to about 11 million people. Unrest among coal miners helped put pressure on the government before the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, though the sector is now a much smaller and less influential part of the economy.

“We need to carefully assess all possible scenarios in order to guarantee that our coal mining regions are developed even if global demand decreases,” Putin said.

The country’s biggest coal producers are privately run, meaning they aren’t facing the kind of financing problems currently being encountered by listed companies elsewhere as banks pull back funding for dirty energy. Suek Plc, owned by billionaire Andrey Melnichenko, and Kuzbassrazrezugol OJSC, controlled by Iskander Makhmudov, are both planning to increase output.

Russia also plans to boost coal production for steel making. A-Property, owned by Russian businessman Albert Avdolyan, bought the Elga coal mine in Russia’s Far Eastern region of Yakutia last year and plans to invest 130 billion rubles to expand output to 45 million tons of coal from the current 5 million tons by 2023. A third stage of Russia’s railroad expansion project will focus on boosting infrastructure for shipping coal out of Yakutia, a Russian Railways official said last month.

“In 2021, many Asia Pacific states have seen their economies recover from the pandemic,” said Oleg Korzhov, the CEO of Mechel PJSC, one of Russia’s biggest coal companies. “We expect that demand for metallurgical coal in Asia Pacific will remain high in the next five years.”

(By Yuliya Fedorinova and Aine Quinn, with assistance from Dan Murtaugh, Akshat Rathi and Ilya Arkhipov)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Beverley kennedy

Metallurgical coal is quite a different item with considerable utility value. Unfortunately media tends to blend it in with the coal used as fuel.