Power problems take a toll on global aluminum output

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

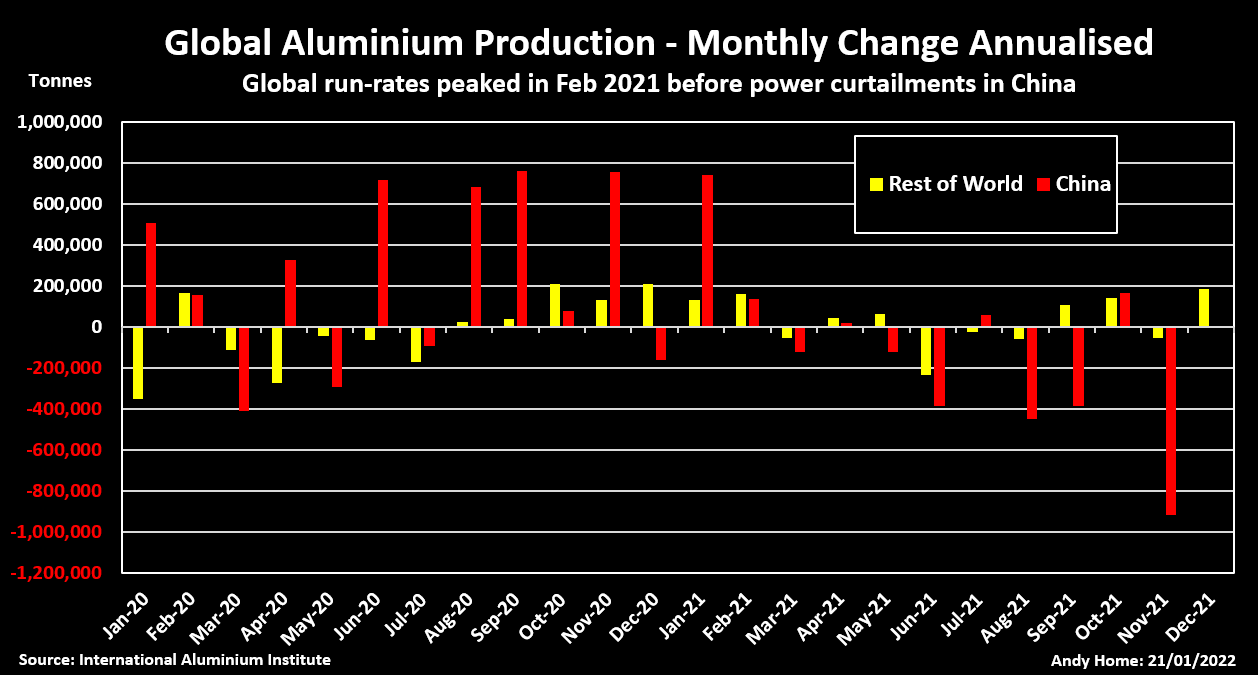

Global aluminum production rates started falling in the closing months of 2021 as power constraints spread from China to Europe.

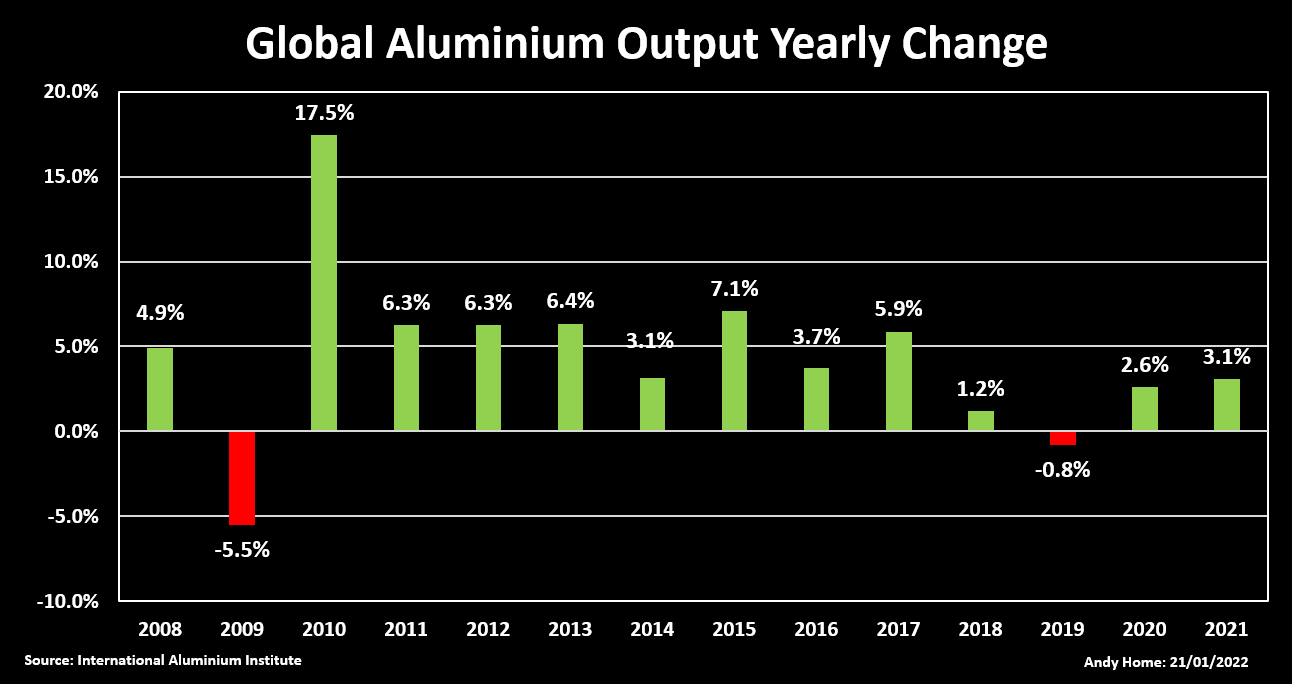

The world’s smelters may have produced a record 67.3 million tonnes of aluminum last year, but all the 3% year-on-year growth derived from the first couple of months.

Annualised run-rates peaked in February at 68.3 million tonnes and slowed to 66.2 million in December, year-on-year production growth turning negative in both November and December.

The resulting supply gap has propelled aluminum prices to decade highs, the London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month price currently sitting above the $3,000-per tonne level, last trading at $3,030.

Physical premiums are also soaring, adding to the pain for aluminum buyers.

Such high prices should incentivise more supply, but everything depends on whether the world has sufficient energy to support power-hungry aluminum smelters.

China powers down

China, the world’s largest primary aluminum producer, was operating at an annualised rate of 37.6 million tonnes in December, according to the latest assessment by the International Aluminium Institute (IAI).

That’s 1.3 million tonnes lower than in December 2020 and 2.1 million tonnes off the February peak.

Drought in hydro-powered Yunnan province curtailed output in what has become a major “green” aluminum production hub earlier in the year.

More smelter hits came in the second half of 2021 from the government’s dual-control energy efficiency targets, which resulted in several provinces mandating curtailments of heavy industry, particularly intensive power users such as aluminum smelters.

China has been the driver of global primary metal production growth for two decades, but the juggernaut seems to have run out of road.

The country turned net importer of unwrought aluminum and alloys in 2020, and imports rose further last year to a record high of 3.2 million tonnes.

China remains a massive net exporter of semi-manufactured products, but has been importing ever more primary metal to make them.

European power crunch

China’s power woes have spread to Europe with a vengeance.

Analysts at Citi estimate around 800,000 tonnes of smelter capacity has been curtailed in the region, with up to 1.2 million tonnes at risk from soaring power prices. (“Global Commodities – Ex-China aluminum deficit looms large”, Jan. 19, 2022).

Production in both Western and Eastern Europe slipped marginally last year, with run-rates in the former slowing appreciably over the fourth quarter.

A strike at Alcoa’s 228,000-tonne per year San Ciprian smelter in Spain was already acting as a drag on regional output before the company announced it would suspend production for two years as part of a peace deal with unions.

As other smelters reduce amperage or fully curtail potlines due to runaway spot power prices, the slowdown in European output will become more pronounced over the coming months.

Europe’s primary metal supply shortfall is forecast by Citi to expand from 3.5 to 4.2 million tonnes.

The growing supply-chain tension is why the European duty-paid premium over the LME cash price has exploded from under $300 per tonne in December to a current $442.

Western restarts

Europe’s aluminum production woes will last as long as the rolling energy crunch and maybe longer if this year’s high spot prices become embedded in higher forward pricing structures.

Output, however, should pick up in both North and Latin America.

A 2.4% drop in North American output last year was largely down to a four-month strike at the Kitimat smelter in Canada, production at the 432,000-tonne-per-year plant falling to 263,000 tonnes in 2021.

The strike ended in October and the plant will undergo a controlled restart this year, according to operator Rio Tinto.

Argentina’s Aluar smelter will also be returning to full 400,000-tonne capacity this year after running at 75% during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, the 447,000-tonne-per-year Alumar plant in Brazil will be brought out of mothballs by its joint owners Alcoa and South32 this year thanks to a renewable power deal.

Latin America saw the fastest production growth of any region last year and is on track to remain a significant driver of global run-rates this year.

China conundrum

However, whatever happens in the rest of the world pales into insignificance relative to China, which last year still accounted for 57% of the world’s primary aluminum production.

Citi estimates potential restarts and delayed new smelters could amount to three million tonnes per year of production capacity coming on line this year.

That would have global implications, both dampening China’s appetite for primary metal imports and boosting its exports of semi-manufactured products.

However, here too everything hangs on energy and power.

Beijing remains committed to peak coal usage by 2025 but it’s clear that last year’ dual-control energy targets were too severe, requiring a series of policy adjustments, not least orders to domestic coal operators to boost production into winter.

There will probably be a lot more fine-tuning by policy-makers seeking to balance decarbonisation with the country’s still fast-growing energy requirements.

That may open a regulatory window for aluminum operators to restart idled and launch new capacity to capitalise on the current boom in prices.

But China’s pledge to start phasing down coal use from 2026 still spells big trouble for its primary aluminum sector.

Despite a collective rush to tap Yunnan’s hydro-energy grid, coal remains the dominant power source for the country’s smelters, accounting for 88% of the 37 million tonnes of aluminum produced in 2020, according to the IAI.

Targets may be adjusted in the coming months, but last year’s crunch may be the first of many, which is why so many analysts are talking about a fundamental shift in China’s aluminum dynamics.

Moreover, Europe’s lengthening list of smelter casualties is a warning sign that power availability poses a fundamental challenge for the aluminum industry globally.

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments