Platinum giant wants in on batteries to ease electric car threat

The world’s top platinum and palladium supplier has an answer to the electric-car boom that may pose a long-term threat to its biggest market: invent a new battery.

Anglo American Platinum Ltd. wants to develop a lithium battery that uses platinum-group metals instead of cobalt and nickel. The aim is to create a new multi-billion dollar source of demand for the metals as electric vehicles reduce the need for traditional fuel autocatalysts.

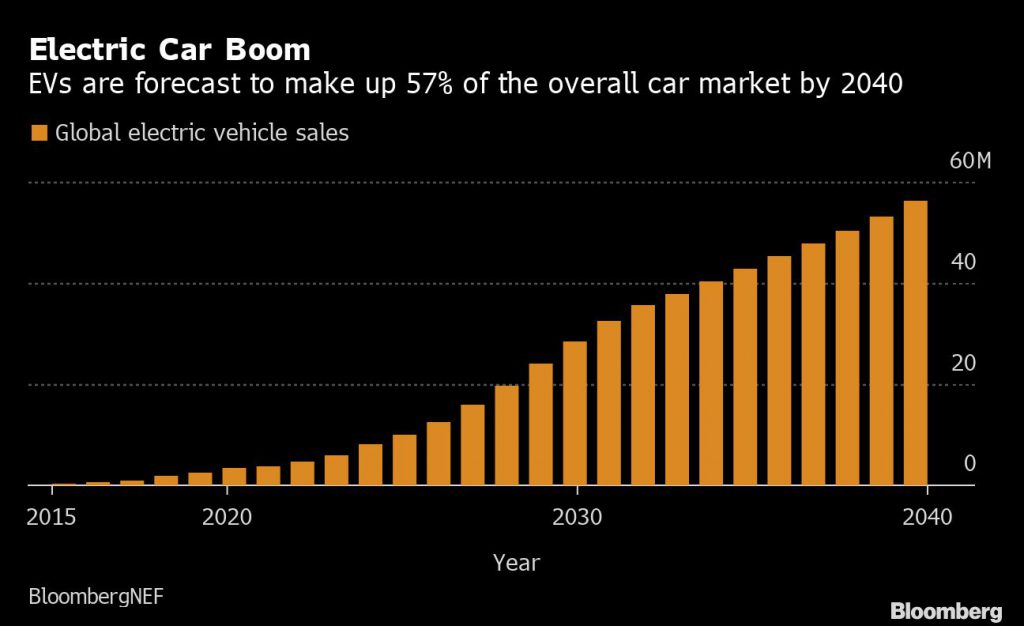

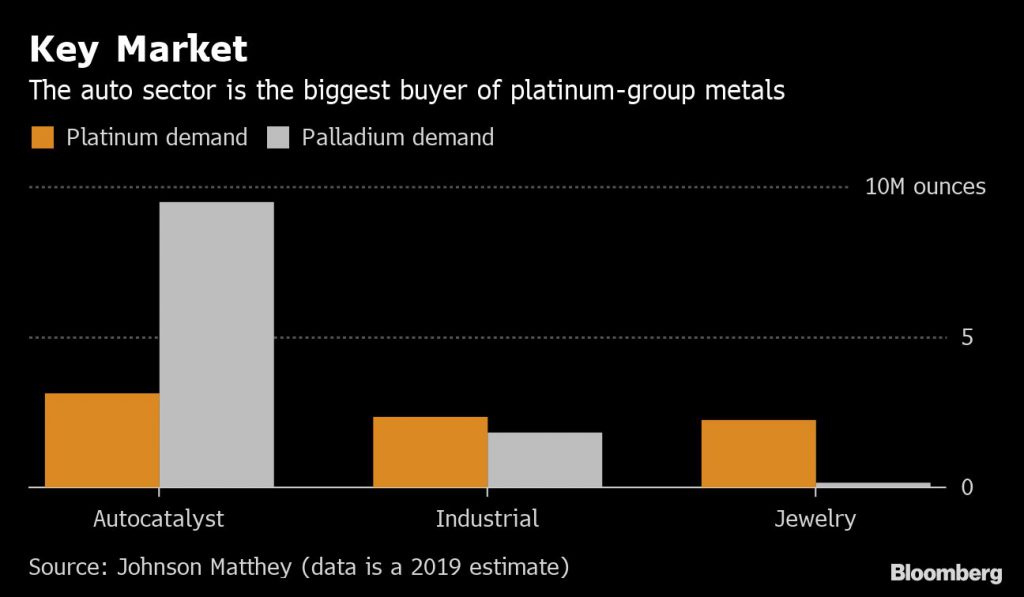

Platinum miners have good reason to be worried. Electric-car sales are forecast to reach 56 million by 2040, making up about 57% of the overall car market versus 2% now, according to BloombergNEF. That could curb demand for autocatalysts, which use platinum and palladium to clean toxic emissions. Platinum is already under pressure — prices are near a decade-low as drivers turn away from diesel engines and supplies remain ample.

“Platinum could play a big role in batteries, but we need to thrift out the other metals to make it viable,” said Mike Jones, chief executive officer of miner Platinum Group Metals Ltd., which is working with Amplats to develop the new battery.

Amplats and Platinum Group Metals have agreed to invest up to $4 million in Lion Battery Technologies Inc. to find a way to use platinum metals to keep batteries cool and create a lighter product with a greater driving range. The venture is studying how much metal will be needed and aims to have a commercial prototype in three to five years.

The idea isn’t new. Academics have researched the technology since the 1990s, but developing it has so far been unfeasible.

“The battery industry is trying to reduce its reliance on expensive/resource scarce material, so I question how hungry the market would be for these batteries”

James Frith, energy storage analyst

There’s no proof yet that such a battery can be mass manufactured, and no technology right now can compete with nickel-cobalt batteries in terms of affordability and performance, said George Heppel, a battery metals analyst at CRU Group.

Part of the challenge is that platinum metals are much more expensive than cobalt and nickel. Early research also shows that 0.5 to 1 ounce of platinum or palladium could be used in the new technology, as much as six times the amount of metal currently used in traditional autocatalysts, said Jones of Platinum Group Metals.

While electric-car sales are already rising, platinum consumption in the auto sector remained fairly robust in recent years amid stricter emissions rules, and the industry has boosted palladium usage, helping push prices to a record. Total demand may rise about 18% for platinum through 2030 and 12% for palladium, according to Noah Capital Markets Ltd.

If platinum metals demand does slow, that would be especially bad news for South Africa, where 75% of all platinum and 40% of palladium are mined. The industry contributes about 96 billion rand ($6.3 billion) to exports from the nation, which is teetering on the brink of a second recession in successive years.

Miners’ support for new battery technology will likely grow, but more industry collaboration is needed to promote demand for metal, Amplats CEO Chris Griffith said. The company is also working with Toyota Motor Corp. and Mitsubishi Corp. to look at ways to use platinum metals in more environmentally friendly ways.

Creating a new battery using platinum metals “would be massively positive for the industry,” said Rene Hochreiter, an analyst at Noah Capital. But “it’s still early stages,” he said.

(By Rupert Rowling and Felix Njini)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments