Peak gold

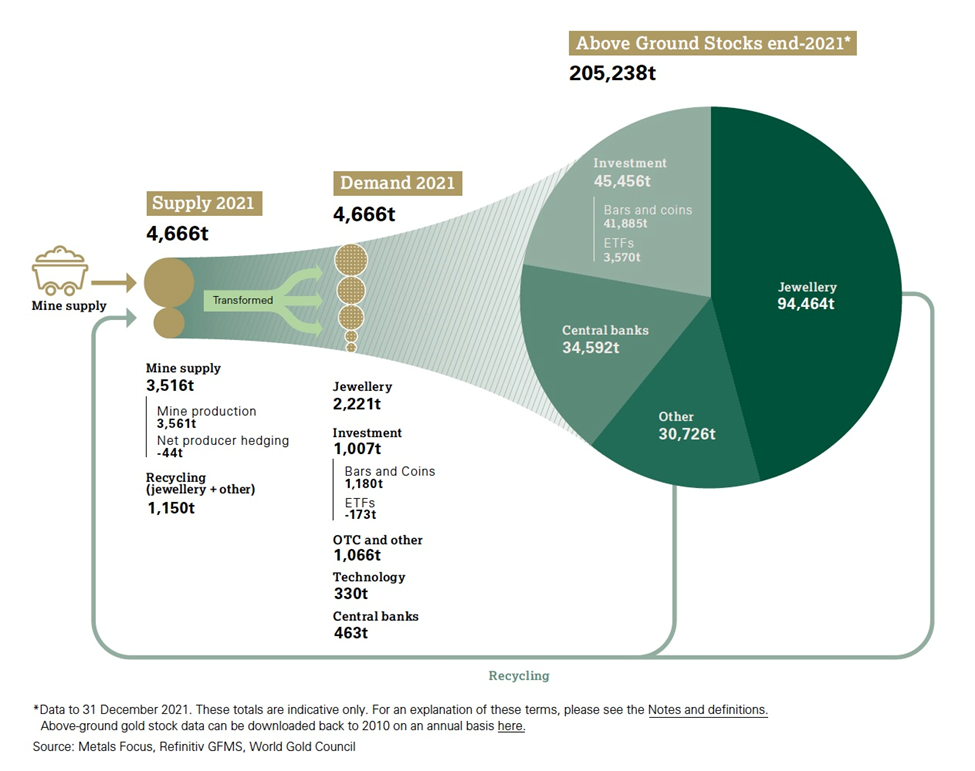

In a world of resource depletion, it falls to gold exploration companies to fill the gap with new deposits that can deliver the kind of production required to meet gold demand, which is currently out-running supply. In 2021, 4,021 tonnes of gold demand minus 3,560.7t of gold mine production left a deficit of 460.3t. Only by recycling 1,150t of gold jewelry could the demand be met.

The gold market continues to experience tightness due to difficulties expanding existing deposits, and a pronounced lack of large discoveries in recent years.

Peak gold

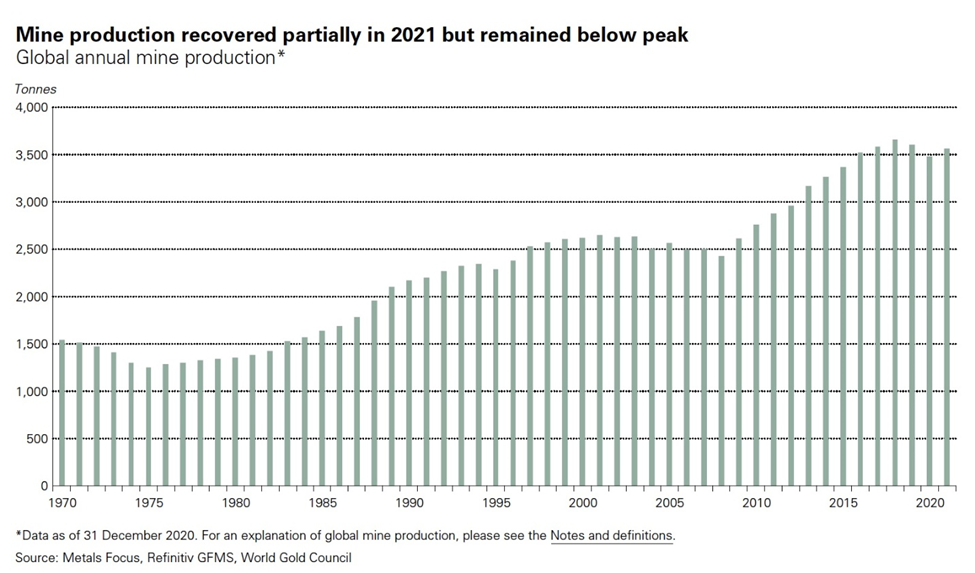

The concept of peak gold should be familiar to most readers, and gold investors. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing, as it has been, by 1.8% a year, for over 100 years. It reaches a peak, then declines.

Peak gold doesn’t necessarily mean gold production will suffer a major fall. However it does mean the mining industry lacks the capacity to ramp up production to meet rising demand; even higher prices would not make that happen, because there aren’t enough mines to tap for more supply.

If gold is indeed becoming scarcer, prices have only one way to go and that’s up, so long as demand for the precious metal is constant or growing.

In a previous article we proved peak mined gold in 2020.

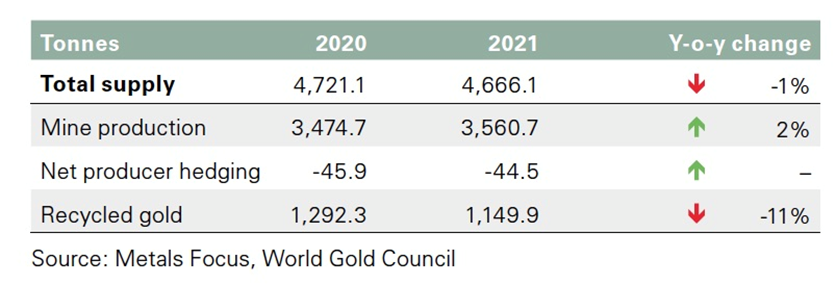

The latest full-year World Gold Council report shows a 1% decline in total gold supply in 2021, compared to 2020, with a sharp drop in recycling more than offsetting higher mine production, which rose 2%, clawing back some of the pandemic-driven losses seen in 2020.

Recycled gold (jewelry) supply fell 11% year on year, a reaction to the modestly lower gold price in 2021 compared to 2020, when gold soared on account of pandemic-related fears, and record-low sovereign bond yields resulting in negative real interest rates — always bullish for gold.

According to WGC, mine production in Q4 2021 fell 1% yoy to 915t. This represented the lowest level of Q4 mine output since 2015. Annual production totalled 3,561t in 2021, 2% higher than 2020 but still lower than 2019 and 3% lower than 2018 — the year when the most gold ever was mined.

In 2019 gold demand reached 4,355.7 tonnes.

The World Gold Council (WGC) reports that 2019 mine production was 3,463.7t.

Gold jewelry recycling was 1,304t, bringing total gold supply in 2019 to 4,776.1t.

If we stop there, we show a slight gold supply surplus of 420 tonnes. Peak gold debunked!

Not so fast, let’s think about those numbers for a minute. In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we, at AOTH don’t, and won’t, count jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t! When we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, we get an entirely different result. i.e. 4,355 tonnes of demand minus 3,463 tonnes of production left a deficit of 892 tonnes.

Let’s fast forward two years, in 2021 total gold supply including jewelry recycling reached 4,666.1 tonnes. Full-year demand was 4,021 tonnes, propelled by Q4 2021 demand which jumped almost 50% to a 10-year high.

No peak gold here, right? Demand is more than satisfied by supply.

But when we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, 1,149.9t, we get 4,021 tonnes of demand minus 3,560.7t of mine production leaves a deficit of 460.3t.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high-grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling thousands of tonnes of gold jewelry over the last few years could demand be satisfied.

This is our definition of peak gold. Will the gold mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough gold, so that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle jewelry? If the numbers reflect that, peak gold would be debunked. We’ve been tracking it since 2019, and it hasn’t happened yet.

As gold mining companies struggle to keep up with demand, we at AOTH see nothing but blue sky ahead for the precious metal.

Let’s turn to hard evidence, such as AOTH’s own research, and a report by Wood Mackenzie on just how valuable the world’s potential future gold mines, mostly controlled by junior resource companies, will be to miners looking to replace reserves.

Woodmac says to avoid a perpetual decline in mined gold, the industry must see a rise in the number of gold projects under development that have a good chance of becoming mines.

How many projects? 44, to be exact. The research firm crunched the numbers in 2020, and found that by 2025 the industry will need to commission 8Moz of projects.

Intuitively, that seems virtually impossible – Wood Mackenzie agrees.

“If all our probable projects were to come online before 2025, this would almost meet the requirement to maintain 2019 production levels,” said Rory Townsend, Wood Mackenzie’s head of gold research.

“The likelihood, however, is that we see some degree of slippage among a number of these assets due to permitting delays, prioritization of other capital projects and changes in scope,” said Townsend.

Consider: in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the gold industry found at least one +50Moz gold deposit and ten +30Moz deposits. Since 2000, no deposits of this size have been found, and very few 15Moz deposits.

Don’t believe us? Here’s Ian Telfer, former Goldcorp chairman, and gold industry expert, giving his argument for peak gold, in 2018:

“In my life, gold produced from mines has gone up pretty steadily for 40 years. Well, either this year it starts to go down, or next year it starts to go down, or it’s already going down… We’re right at peak gold here.”

To get world gold mine production back to the point where it can meet the required annual demand without recycling jewelry, the industry has two choices: it can mine more gold, or it can discover new gold.

Squeezing more gold out of existing deposits has its challenges. Reserves are getting depleted, and mines are having production problems, including lower grades, labor disruptions, protests, etc. Remember, to avoid a perpetual declined in mined gold, by 2025 the industry will need to commission 8Moz of projects (Wood Mackenzie).

This week it was reported that Burkina Faso, the 12th largest gold mining country in the world, is set to produce 13% less gold this year than in 2021, due to mine closures. Mines there are closing because of security risks to employees; 2022 is shaping up to be the deadliest year since a civil conflict began a decade ago, pitting the government of Burkina Faso against Islamic militants affiliated with Al Qaeda.

But finding and exploiting new gold deposits is even harder, more expensive and risky.

Few gold exploration projects have the economics, scale, jurisdiction and money-raising capabilities backing them, to become mines. Those with the staying power to make it through the various development stages, from initial discovery to drilling to resource definition to first production, will be the belle of the ball, so to speak, with many major gold miners cueing up for the first dance.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Jennifer Anne Nettles

More info