Nobel laureate says better batteries can cement electric car era

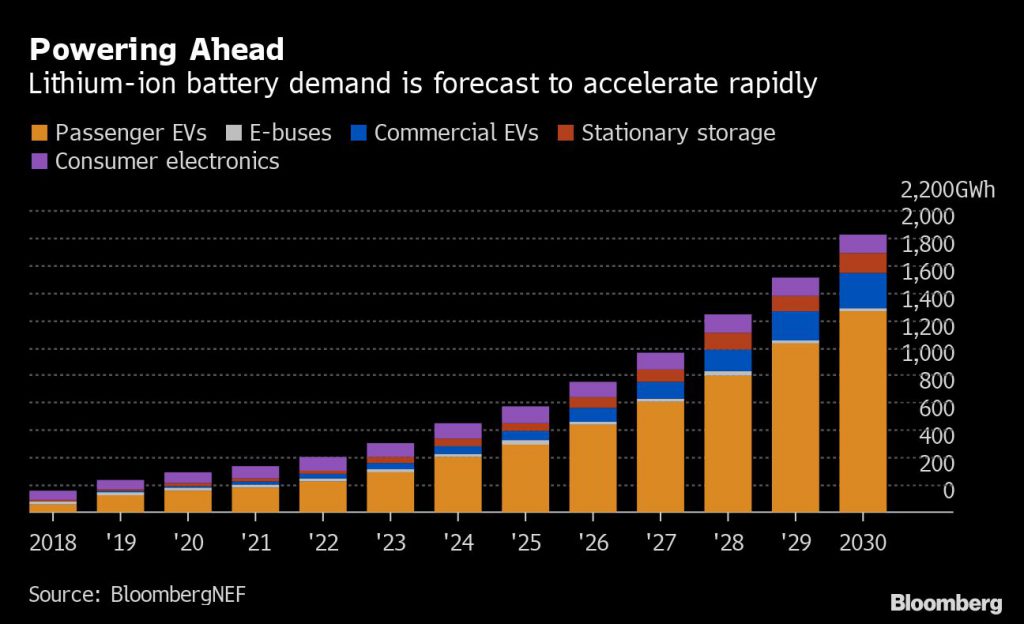

The Nobel Prize-winning scientist whose research proved critical in developing lithium-ion batteries said the ubiquitous technology energizing iPhones and Teslas is poised to become more powerful and cheaper — keys for unlocking the mainstream adoption of electric vehicles and home-energy storage units.

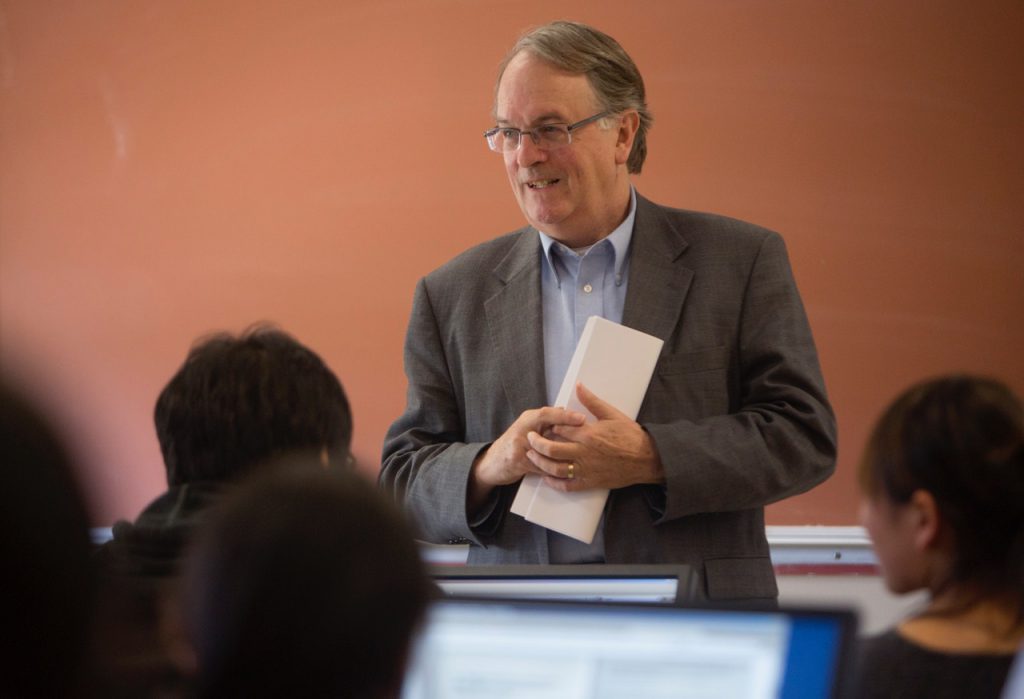

M. Stanley Whittingham, 77, is part of a trio jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry this month. He still works to make batteries better, more than four decades after his initial breakthroughs in a New Jersey laboratory while employed by Exxon Mobil Corp., where he received the patent for a rechargeable lithium-ion battery.

They are going to become cheaper and more readily available to everyone, and the research we’re doing will increase the energy density and make them safer at the same time,” Whittingham, a professor at the State University of New York at Binghamton, said Wednesday in an interview in Sydney.

Further improvements to the technology may also bolster efforts to combat climate change by enabling greater use of renewable-energy sources, Whittingham said. His outlook may offer comfort to automakers and utilities currently grappling with weaker EV sales in China, the top market, and safety setbacks in the deployment of grid-scale batteries.

The following excerpts from the interview have been condensed and edited.

How can battery technology improve?

Whittingham: What we are now looking at is increasing the energy density — twice as much in a given weight or volume, cutting the price and also seeing it really get into all devices, so we’ll have cleaner cities and we’ll have more electric vehicles in the cities.

What would better technology mean for electric cars?

Whittingham: It’ll allow cars to go farther, but perhaps more importantly it’ll allow batteries to be smaller. If we can put twice the energy in the same volume, then we can make batteries much smaller than they are today. You use less material, so they’d be less costly, and so that’ll help them take over the market. Electric vehicles have got to be at a price where the consumer considers them as a realistic option, and they have got to go a reasonable distance.

Will the recharging of EV batteries get faster?

Whittingham: For car batteries, the issue if you charge them in a short period of time is that you need a huge current and huge voltage, and, in the end, you are going to reduce the lifetime of the battery. If you look at the sellers of electricity, they don’t particularly want them to be charged very fast.

What is the future for lithium-ion batteries?

Whittingham: Lithium-ion is going to dominate for at least the next 10 years because there is nothing really on the horizon. Toyota Motor Corp. and a whole host of American companies are working on solid-state batteries, though it’s not clear how much those will cost to manufacture, and it’s not clear yet whether you’ll get a decent amount of power. They may work for things like iPhones initially, but there are some big questions before they are used in larger-scale systems.

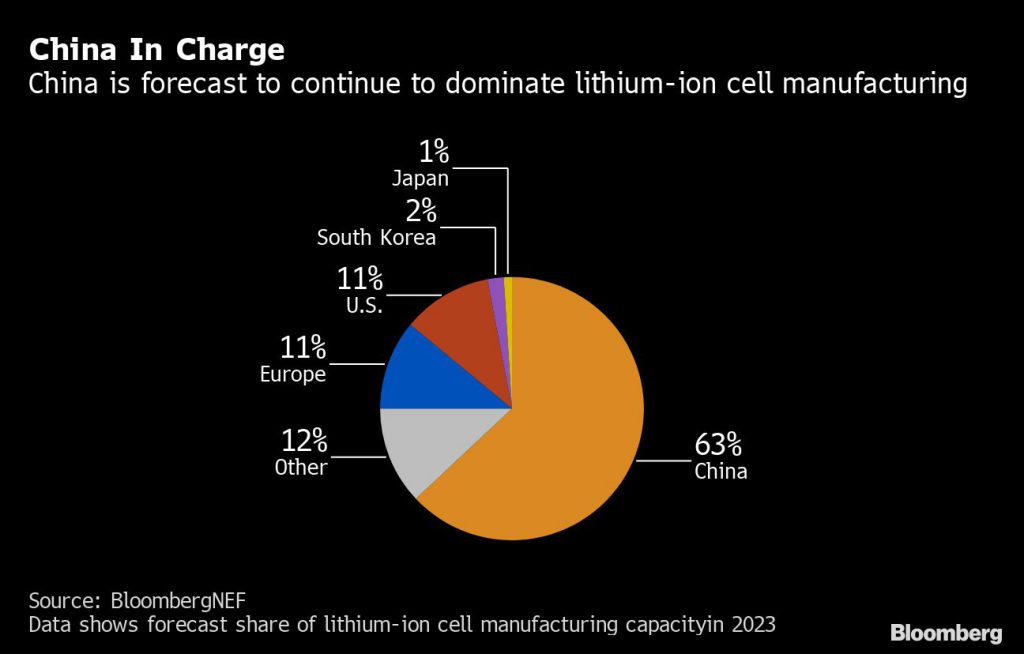

Is there a need to challenge China’s manufacturing dominance?

Whittingham: In the U.S. we are worried about China dominating, and clearly places like Germany are as well. It’s important for every country. You do want to be totally independent. If anything goes wrong in China, then you are stuck, and that’s not acceptable.

How can batteries change the energy-storage business?

Whittingham: The sun shines a lot when you don’t particularly need all that power. And in Texas, the wind blows at 3 a.m., when you don’t need it. Batteries are incredibly useful for storing that energy. After PG&E has been cutting off the power in California, people are going to say that if they have got a $2 million home, then they are going to want their own source of energy and their own source of storing it so they are not affected by these events.

What is your current research seeking to achieve?

Whittingham: I’m involved in two large projects, one of which I lead –- and that’s a fundamental science project trying to see what are the ultimate limits of these batteries. Right now, we only get 25% of theoretical capacity of them, so that’s 75% that’s dead volume or dead weight. It’s the top folks in the world working on that project.

Why did your research in the 1970s make fire chiefs nervous?

Whittingham: We never had a battery burn up, but after you’ve cycled the battery many times you want to see what happened to it, so you pull them apart. That’s what causes a fire. The fire trucks came in at least twice, and the research site was right across the street from the Exxon refinery in New Jersey. I don’t think they like fires near a refinery. There was a highway between us, but they still worried.

(By David Stringer, with assistance from Haidi Lun)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Troy Brooks

So he is saying what causes fires is recycling?