Nickel squeeze threatens London’s place at heart of metals trade

The first short squeeze to plunge the London Metal Exchange into an existential crisis came over a century ago. In 1887, French industrialist Pierre Secretan set out to corner the copper market, sending prices more than doubling before he lost his grip and they collapsed.

In the years since, the exchange has survived world wars, scandals and defaults to cement its place as a City of London institution: the home of global benchmark prices for the world’s key industrial metals.

That status is now under threat. The reason is another short squeeze, this time in nickel, that is wreaking havoc through the metals world. Investors are furious with the LME for allowing prices to soar 250% in less than two days, then retroactively canceling $3.9 billion in trades. When it tried to reopen the market, the exchange’s electronic trading system malfunctioned repeatedly.

The LME’s outsized role in how industrial metals are bought and sold means that angry traders and investors have few alternatives. But the fallout from the nickel squeeze will cast a long shadow, embroiling the exchange in investigations and lawsuits for years, and raising questions about its structure, ownership and oversight.

“Suddenly the LME just looks incompetent,” says Mark Thompson, a mining executive and former metals trader at Trafigura Group who has emerged as one of the exchange’s most outspoken critics. “They need root-and-branch reform.”

In an interview, LME Chief Executive Officer Matthew Chamberlain says the past two weeks have been an “incredibly trying time” for the market, and he is focused on ensuring that “an event of this nature never happens again.”

Chamberlain’s immediate priority is to get the nickel market functioning again. The LME’s software glitch was due to be patched over the weekend, and the exchange is widening its trading band from Monday to allow prices to fall up to 15% — which would bring it closer to where traders believe the market might find willing buyers.

The LME, which was founded in 1877 and is now owned by Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd., performs multiple roles. For the metals industry, it’s an essential utility, generating the prices that are embedded in almost every contract. For investors, banks and brokers, it’s a place to make money.

It is also an institution that has had to be dragged into the 21st century, and not just when it comes to technology. It was only in 2019 that it banned its floor traders from drinking alcohol during the day and cracked down on member companies holding parties at lapdancing clubs and casinos during their annual gathering in London.

Chamberlain has spent much of his career trying to woo new participants like hedge funds, without alienating the exchange’s core physical industry users.

On March 8, as nickel prices shot to more than $100,000 a ton, those tensions came to a head. When the LME decided to cancel hours of trades and rewind prices to $48,078, it chose the physical industry over the funds. Effectively, it was a multibillion-dollar bailout of Chinese nickel tycoon Xiang Guangda, who held a massive bet that prices would fall, and his banks, led by JPMorgan Chase & Co.

But the exchange was also throwing a lifeline to other, smaller nickel traders and the specialist metals brokers who service them, who were also in trouble when prices spiked.

If the events of March 8 were high drama, last week the LME descended into farce.

Trading in nickel had been due to resume at 8 a.m. on Wednesday, but was delayed for several hours by a software glitch. More trades were canceled. Similar embarrassing problems recurred over the next two days.

Chamberlain blames “a bug in the underlying third-party software” that the exchange missed as it rushed to put in the new price limits in place. “If we had waited for that bug to be fixed, then we would have had to delay the reopening .”

The debacle has thrown owner HKEX’s plans for the LME into disarray. For much of the past ten years, the LME has pinned its hopes for growth on attracting U.S. hedge funds and other financial investors.

Last year, Chamberlain clashed with the more traditional users of the LME over proposed changes designed to make the exchange more attractive to financial investors – including closing its iconic open-outcry trading floor, where dealers bark orders at each other from red leather couches.

Now many of those same financial investors say they may abandon the LME. Some are working on lawsuits in the U.S. and the U.K., according to people familiar with the matter.

A portfolio manager at one large macro hedge fund says he has already stopped trading any LME contract for his relative value book, that bets on price differences between commodities, equities and currencies. Alex Gerko, founder of XTX Markets, a large quantitative trading firm, has dubbed the LME the “Soviet Metal Exchange”.

Chamberlain concedes that it will take work to win back investors’ trust.

“If we are unable to rebuild credibility with the financial market, that certainly will impact our ability to grow,” he says.

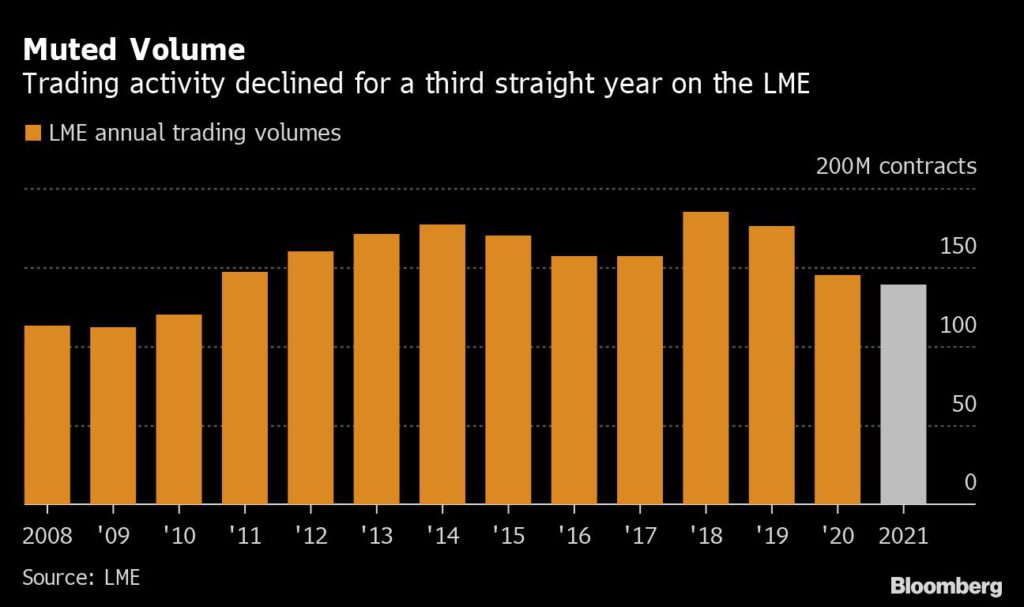

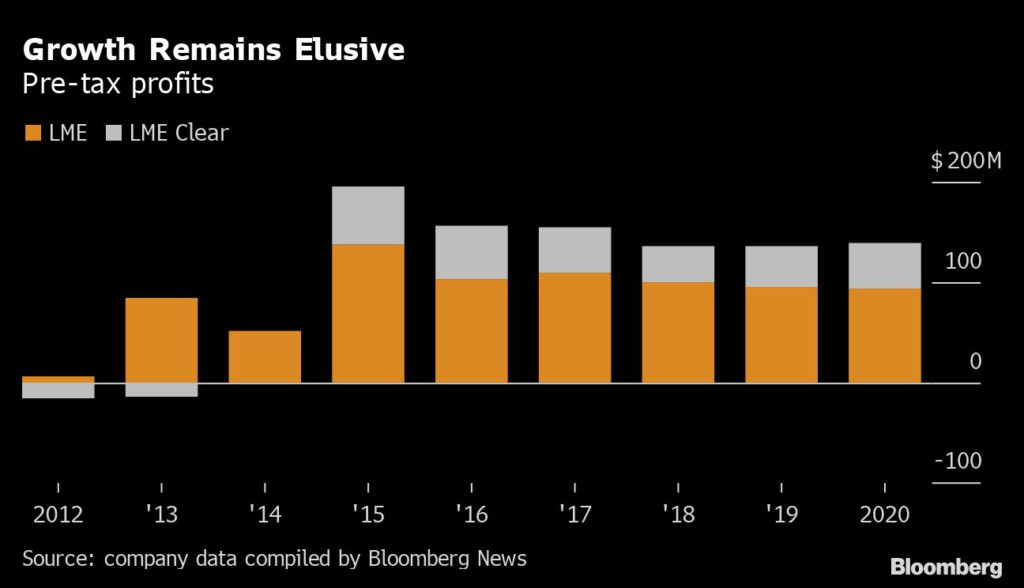

Even before the nickel crisis, the LME had been trying without success to increase activity. Volumes have been falling and profit flatlined. Since the crisis this month, volumes have already taken a hit as trading seizes up in the nickel market, while declining activity in its other flagship contracts points to a broader hesitation about using the exchange.

For Chamberlain, it’s a deflating coda to a decade-long LME career. He had been halfway out the door when the crisis hit – he was due to leave the exchange at the end of April to run a crypto startup. He declines to confirm whether he’s still leaving, saying only: “I am still here and I will do whatever I can do to be helpful to resolve the situation.”

The task is nothing less than securing the future of the exchange.

With daily price limits in place to prevent wild moves in the future, Chamberlain is turning the focus to the over-the-counter market, where banks strike bilateral deals linked to the LME but away from the exchange’s oversight. The large majority of Xiang’s nickel short position was held through such positions. He also said the exchange would seek tighter position limits, and stronger supervision of traders with large short positions.

As financial investors talk about abandoning the LME, another risk for the exchange is that the physical metal industry backs away as well. Two weeks without normal nickel trading caused chaos for manufacturers and dealers. Spanish stainless steel maker Acerinox stopped taking new orders.

Could other exchanges capitalize on the LME’s struggles?

There are few alternative venues for trading metals like nickel, aluminum and zinc. CME Group Inc., which has a popular copper contract, is looking at opportunities in nickel but is unlikely to make any hasty moves, according to people familiar with the matter. A CME spokesperson declined to comment. The other major metals exchange, the Shanghai Futures Exchange, is largely inaccessible for international traders.

Still, with the LME nickel market frozen over the past two weeks, the eyes of the world turned to the Shanghai contract.

Smaller sibling

“It’s not impossible to imagine a scenario where, in five or ten years, it’s not the LME that’s the global marketplace, with Shanghai as its smaller sibling, but the other way around,” says Duncan Hobbs, research director at trading house Concord Resources Ltd.

The crisis also is raising questions about HKEX’s plans. The Hong Kong exchange’s new CEO, former JPMorgan banker Nicolas Aguzin, has yet to set out his vision for the LME. And there was no shortage of other suitors for the LME when HKEX bought it in 2012. Thompson, the former Trafigura trader, says the events of the past two weeks suggest that HKEX is the wrong owner for the LME.

An HKEX spokesperson declined to comment.

To be sure, HKEX has long seen the LME as a strategic investment, says Shujin Chen, head of China FIG research at Jefferies Hong Kong Ltd. But it will probably have to stomach an array of lawsuits from disgruntled traders, as well as heightened regulatory scrutiny of an asset that had been viewed by some within the exchange as a poor acquisition.

Asked whether he thought HKEX should consider selling, Chamberlain replies: “I don’t want to talk to what HKEX may or may not want to do. But I would say that we’ve observed in the past that HKEX has always been a supportive owner of this exchange, and has always wanted to do what’s right for the exchange and its community.”

(By Jack Farchy, Kiuyan Wong and Mark Burton, with assistance from Archie Hunter, Isis Almeida and Yvonne Yue Li)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments