Nickel spreads collapse as banks face soaring financing costs

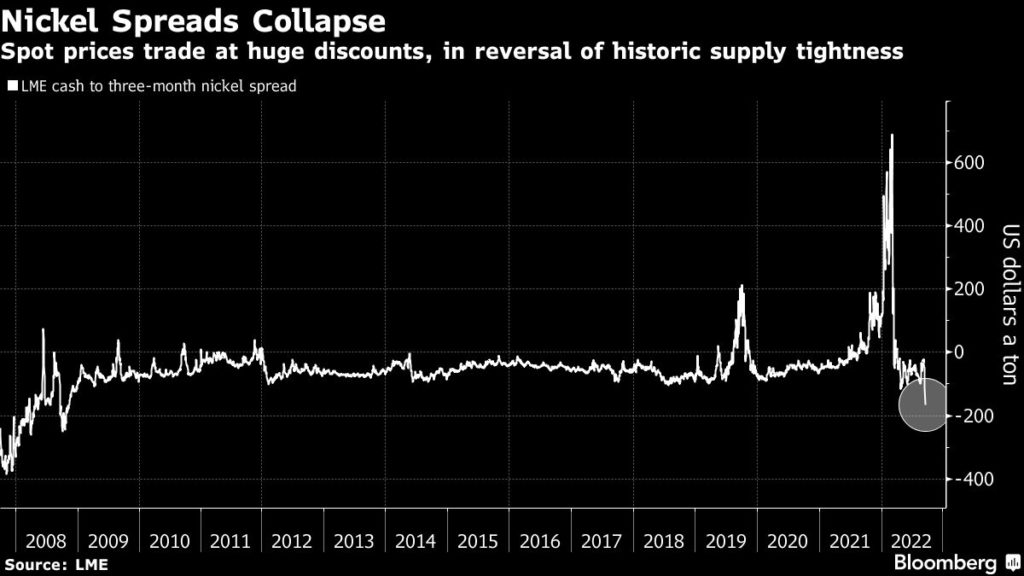

Nickel sales by commodities-dealing banks hit by soaring borrowing costs have caused spot contracts to plunge to the deepest discount to futures since the 2008 financial crisis.

The jump in the dollar and borrowing costs have made it much more expensive for banks to finance London Metal Exchange positions in recent days, particularly for European institutions funding dollar-based deals. Nickel is the highest-priced metal actively traded on the LME, and moves in currency and rates markets have left lenders rushing to unload positions that are becoming more costly to hold, according to several traders involved in the market.

Spot prices typically trade at narrow discounts to three-month futures when supply is ample, in a condition known as contango. But the spread has widened dramatically, hitting negative $167 a ton on Monday.

“The reality of the situation is that banks have been sitting on metals to finance, and nickel is one of the more expensive metals to hold,” Alastair Munro, a commodities sales executive at Marex, said by phone. “You can see from the moves in the spreads that this is a risk-reduction event, and any bank that’s active in financing will have been involved.”

The change in the spread is a big turnaround from earlier this year, when short-term nickel prices fetched a steep premium, indicating tight supply. The closely watched cash-to-three-month measure spiked to more than $800 during an unprecedented squeeze in March, which nearly led to the collapse of Tsingshan Holding Group Co., the world’s top producer of nickel and stainless steel.

The main driver of the plunging spread over the past week has been selling on the part of banks who’ve held nearby positions as hedges against long-term sales to carmakers, who use nickel in electric-vehicle batteries, traders said. There have been similar moves in longer-dated spreads, which aren’t as actively traded and are primarily used to hedge long-term exposure in physical markets.

Volkswagen AG has been particularly active in hedging its exposure to nickel prices, covering a portion of its requirements up to nine years ahead. That’s made it one of the largest holders of long positions in London nickel contracts, and it reaped a $3.8 billion windfall on those and other commodity positions earlier this year as prices surged.

But prices have since slid, with fears over curbs on Russian supply giving way to worries about a worsening demand outlook. Benchmark three-month prices fell 0.6% after earlier dropping as much as 1.2% to $21,950 a ton on Tuesday — compared with a peak of $55,000 during the March squeeze.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts including Nicholas Snowdon see close to 30% downside for the nickel price into year-end. They lowered their three-month price forecast for nickel prices to $16,000 a ton from a previous projection of $26,000. They also downgraded their forecast for nickel prices in the next six and twelve months to $18,000 and $20,000, respectively, from previous projections of $30,000 and $28,000, respectively. Their new 2022 and 2023 average price forecast is now $24,300 and $18,500, respectively.

Nickel prices had actually exceeded $100,000 on March 8, before the LME halted trading and canceled billions of dollars of transactions that had taken place during the day.

The exchange’s handling of the crisis attracted widespread criticism, and the bourse is now facing lawsuits from investors and investigations from regulators. The nickel market itself is still suffering from low liquidity in the wake of the March squeeze.

“In an illiquid market you do see these moves where the spreads can go beyond the full cost of finance, even though on paper it doesn’t appear to make sense,” Marex’s Munro said. “It would make sense for some market participants to start borrowing some of these forward curves, given the scale of the moves.”

(By Mark Burton, with assistance from Yvonne Yue Li)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments