Moon mining – Why major powers are eyeing a lunar gold rush

Russia launched its first moon-landing spacecraft in 47 years on Friday amid a race by major powers including the United States, China and India to discover more about the elements held on the earth’s only natural satellite.

Russia said that it would launch further lunar missions and then explore the possibility of a joint Russian-China crewed mission and even a lunar base. NASA has spoken about a “lunar gold rush” and explored the potential of moon mining.

Why are major powers so interested in what is up there?

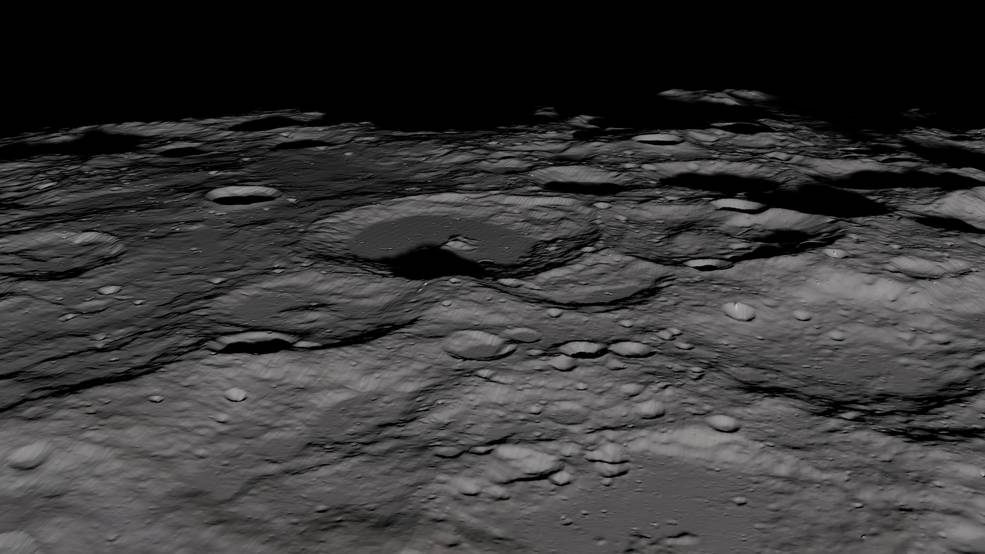

The moon

The moon, which is 384,400 km (238,855 miles) from our planet, moderates the earth’s wobble on its axis which ensures a more stable climate. It also causes tides in the world’s oceans.

Current thinking is that it was formed when a massive thing collided with earth about 4.5 billion years ago. The debris from the collision came together to form the moon.

Temperatures vary: in full Sun, they rise to 127 degrees Celsius while in darkness they plummet to about minus 173 degrees Celsius. The moon’s exosphere does not give protection against radiation from the Sun.

Water

The first definitive discovery of water on the moon was made in 2008 by the Indian mission Chandrayaan-1, which detected hydroxyl molecules spread across the lunar surface and concentrated at the poles, according to NASA.

Water is crucial for human life and also can be a source of hydrogen and oxygen – and these can be used for rocket fuel.

Helium-3

Helium-3 is an isotope of helium that is rare on earth, but NASA says there are estimates of a million tonnes of it on the moon.

This isotope could provide nuclear energy in a fusion reactor but since it is not radioactive it would not produce dangerous waste, according to the European Space Agency.

Rare earth metals

Rare earth metals – used in smartphones, computers and advanced technologies – are present on the moon, including scandium, yttrium and the 15 lanthanides, according to research by Boeing.

How would moon mining work?

It is not entirely clear.

Some sort of infrastructure would have to be established on the moon. The conditions of the moon mean robots would have to do most of the hard work, though water on the moon would allow for long-term human presence.

What is the law?

The law is unclear and full of gaps.

The United Nations 1966 Outer Space Treaty says that no nation can claim sovereignty over the moon – or other celestial bodies – and that the exploration of space should be carried out for the benefit of all countries.

But lawyers say it is unclear whether or not a private entity could claim sovereignty over a part of the moon.

“Space mining is subject to relatively little existing policy or governance, despite these potentially high stakes,” The RAND Corporation said in a blog last year.

The 1979 The Moon Agreement states that no part of the moon “shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person.”

It has not been ratified by any major space power.

The United States in 2020 announced the Artemis Accords, named after NASA’s Artemis moon program, to seek to build on existing international space law by establishing “safety zones” on the moon. Russia and China have not joined the accords.

(By Guy Faulconbridge; Editing by Peter Graff)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments