MMT, emerging markets and the scramble for resources

In our last article, we discussed a proposed new economic model for China, Modern Monetary Theory. MMT is not only a means for China to build a manufacturing base from which to generate a huge range of new products including high technology, it’s a template that other developing nations/ emerging markets can use to fund major spending initiatives they previously couldn’t afford, since it involved changing their currencies into US dollars, the world’s reserve (and most expensive to convert to) currency.

If it catches on, MMT could open the floodgates to some major infrastructure spending initiatives worldwide.

The upshot? A global need for commodities that surpasses anything we have ever seen before, even the last commodities super-cycle in the 2000’s, driven by China’s insatiable hunger for fuels, metals, building materials and foodstuffs, as its economy grew at double digits.

Arguably, the proving ground for MMT will be China.

The country has big plans for manufacturing, i.e. a $2.3T infrastructure package consisting of thousands of major projects put forth by local governments. Statements from China’s leadership indicate China is moving into high-technology sectors that will lead the world and relegate the US to second place.

The question is, how does China pay for it?

The country’s local governments are reportedly facing a fiscal crunch because of a plunge in land sales, a major source of revenue, constraining their ability to spend and forcing them to borrow more.

On top of that, GDP growth in China is set to lag the United States, something that concerns Beijing. Calls are therefore growing louder for the Chinese government to boost fiscal stimulus, regardless of higher debt levels, an approach that is drawing comparisons to MMT.

So what exactly is it?

Modern Monetary Theory is a new way of approaching the US federal budget. Rather than obsessing about how large the debt has grown (over $30 trillion) and the ongoing annual deficits that fuel debt, MMT says we should focus on spending, especially on areas that don’t fuel inflation, which is the chief criticism of MMT.

Curb inflation and the debt can keep growing, with no consequences. This is because the US government can never run out of money. It just keeps printing it, because dollars are always in demand (with the dollar being the reserve currency, and commodities are traded in dollars).

The government doesn’t need to “come up with the money” to spend it. It just prints money.

While MMT is associated with rich, developed economies, in our last article we suggested that China is a good candidate for the economic model, since it has already taken steps to distance itself from the US dollar, and that so long as China’s government borrows money in its own, sovereign currency, the yuan, it can keep printing money to pay the interest. It’s a way for China to finance the trillions of dollars in infrastructure spending the central government has planned.

While we have in the past criticized MMT, for it being fiscally irresponsible, it could actually work for emerging economies; we see what is being proposed for China as a model for them.

Providing they print money in their own currency, there is nothing stopping any country from lending to local governments, state-owned enterprises, etc., who can just pay the interest on the loans, in local currency (as China’s MMT advocates are proposing it does). And why wouldn’t they do it?

A resource-finite world

It doesn’t take a Nobel prize-winning economist to work out what happens next. As countries cue up for the raw materials required to fulfill their infrastructure programs, all paid for with borrowed money, the already tight markets for industrial metals like copper, nickel, aluminum and zinc, will tighten further. The surge in demand leading to higher prices will prompt countries that have these materials to hold onto them. A new wave of resource nationalism will wash over the mining sector.

Resource nationalism

Countries rich in minerals are frequently looking at ways to get more money from miners, the most common tactic being to hike royalty payments.

Governments have also gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with requirements such as mandated beneficiation/export levies and limits on foreign ownership:

- Mandated beneficiation/export levies – Governments are imposing steep new export levies on unrefined ores. Minerals processed in-country capture more of the value chain as the products achieve higher prices.

- Increasing state ownership – Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

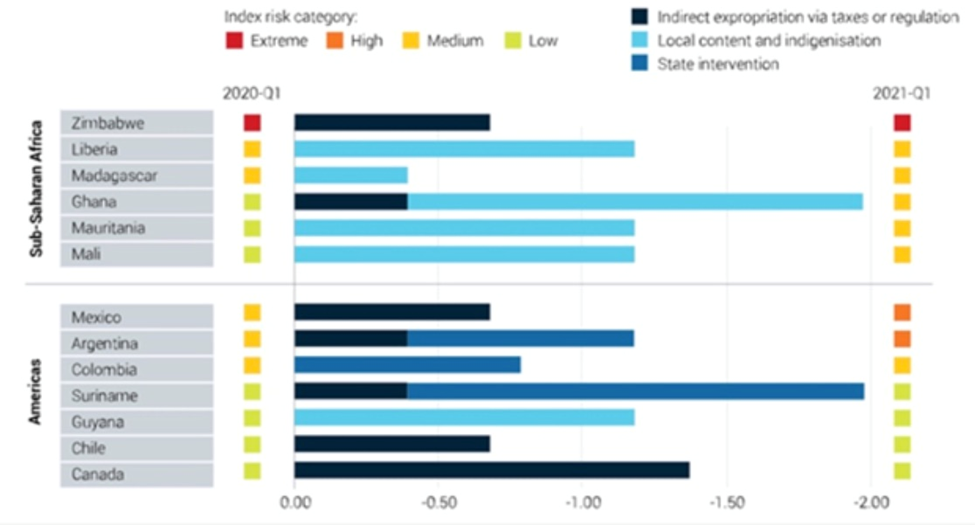

Risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft tracks incidents of direct expropriation and nationalization, summarizing the degree of risk in an annual resource nationalism index.

Sixty six of 198 countries in the latest (2021) index, or 33%, have tightened their grip on resource wealth since 2017. Latin America stands out as the region where the risk of expropriation and tax increases have increased the most.

Resource nationalism was happening long before covid and the war in Ukraine stretched supply lines for commodities. Always remember we are living in a resource-finite world.

Arguably, we are at the point where no significant new technologies will be invented to make mining more efficient or profitable — unlike the “shale revolution” brought about by directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing i.e. fracking. These processes allowed previously uneconomic “tight” oil and gas formations to be drilled, transforming the United States from a net oil importer to a net oil exporter.

In the same way, farming and ranching have reached the limits of technology. The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since. Unfortunately though, high-yield growth is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is mostly because of an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted soils and irrigation has depleted aquifers.

Throw climate change into the mix, and you’re looking at a serious problem. As the planet warms, both arable land and water are becoming scarcer.

Water

Last year in central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its grains and iron ore to global markets (flows were @ 55% of the historical average).

Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, has problems with water and is having to desalinate seawater used for mining copper in the country’s arid north. We are already seeing major copper mines in Chile having to curtail production due to water shortages brought on by a decade-long drought.

A lack of fresh water for processing is likely to become more of an issue for mining companies in future, especially as the planet warms and becomes drier, and miners are having to compete with other water users, such as farmers, local towns and indigenous settlements.

Metals

BMO estimates the country’s 2022 copper production has slowed to a pace where it could be lower than 2004, when mine output was slightly over 5.4 million tonnes, equivalent to 37% of the world’s production.

The Chilean government is so worried about its water supplies, it’s proposing to nationalize its copper (and lithium) industry. The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining near glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

While the changes to the constitution still face hurdles, the idea has miners nervous about their Chilean operations. A new mining royalty bill would see an “ad valorem” tax corresponding to 1% of annual copper product sales. An amended version of the legislation was passed by the Chilean Senate in January.

Similar fears exist in neighboring Peru, the world’s second-largest copper producer. There, the government wants to raise mining taxes by 3 to 4 percentage points, an amount that Peru’s mining chamber says would put more than $50 billion in future investments at risk. On April 20 the following article was posted on Mining.com: Fifth of Peru copper mining goes offline with more shutdowns likely

We already know that we don’t have enough copper for more than a 30% market penetration by electric vehicles. For solar power we are talking about finding 16 times the current annual production of aluminum, and 23 times the current global output of copper. Up to six times the current production levels of nickel, dysprosium and tellurium are expected to be required for building clean-tech machinery.

Yet there is a more immediate problem, and that is high electricity costs.

Driven by the need to decarbonize due to increasingly apparent climate change, governments around the world right now are choosing to de-invest from oil and gas, and instead are plowing funds into renewable energies even though they aren’t yet ready to take the place of standard fossil-fueled baseload power, i.e., coal and natural gas.

Natural gas

We have seen this foolish endeavor playing out in Europe, where natural gas prices have hit records due to coal plants being shut down as well as nuclear plants shelved, such as in Germany and France. The skyrocketing cost of electricity is being borne by ordinary citizens who had no part in this dumb policy of “premature decarbonization”.

This problem has been made much worse by the war in Ukraine.

Russia supplies about a third of European gas demand. In mid-March the European natural gas benchmark surged as much as 79%, to the equivalent of more than $600 a barrel, on concerns over the availability of the fossil fuel.

The Kremlin has threatened to cut flows via the existing Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Germany, as retaliation over Western sanctions, and on Wednesday it blocked natural gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria. European leaders, who are struggling to find alternate sources of NG, condemned the move as “blackmail”.

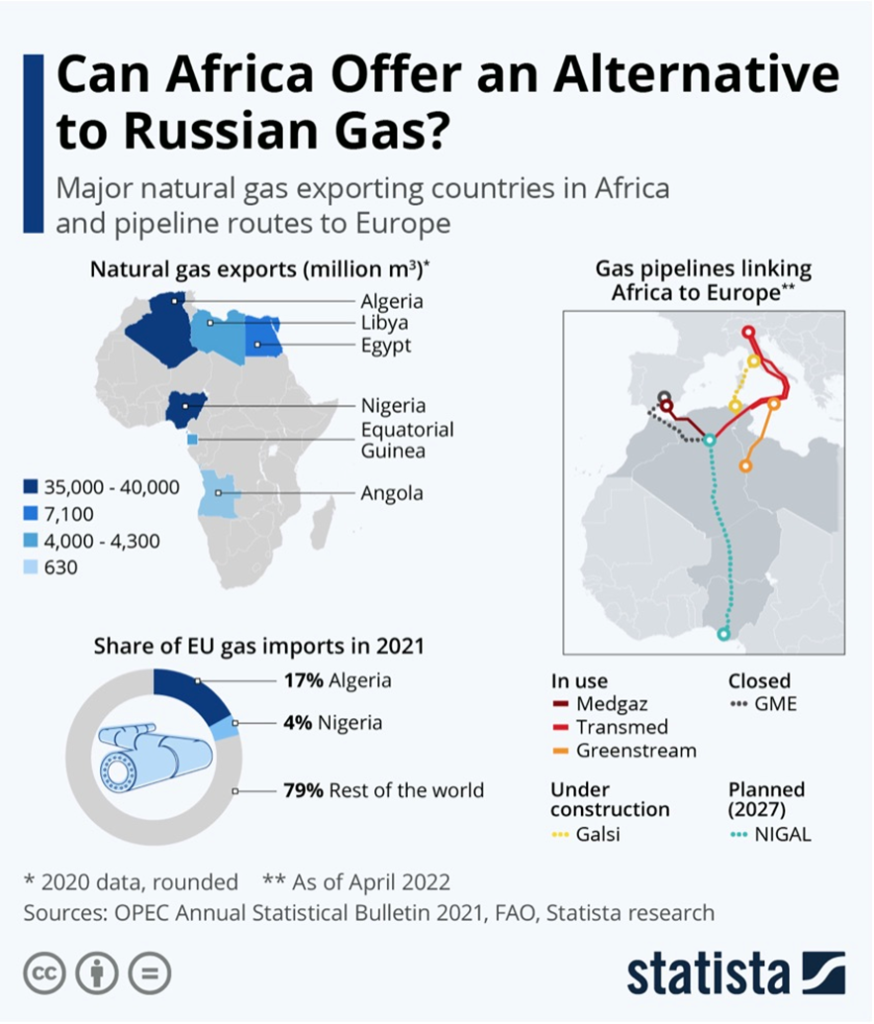

Africa is among the regions that could help Europe to break its dependence on Russian gas. Italy is reportedly conducting a diplomatic campaign to discuss diversifying its energy imports, having carried out recent visits to Algeria and Egypt. The continent’s largest natural gas exporters by far are Algeria and Nigeria, ranked 7th and 8th globally.

Food

Beyond minerals and hydrocarbons, the war in Ukraine reminds us we are also living in a resource-finite world with respect to food. The country often described as Europe’s breadbasket has restricted shipments of foodstuffs to ensure its population is adequately supplied during the conflict.

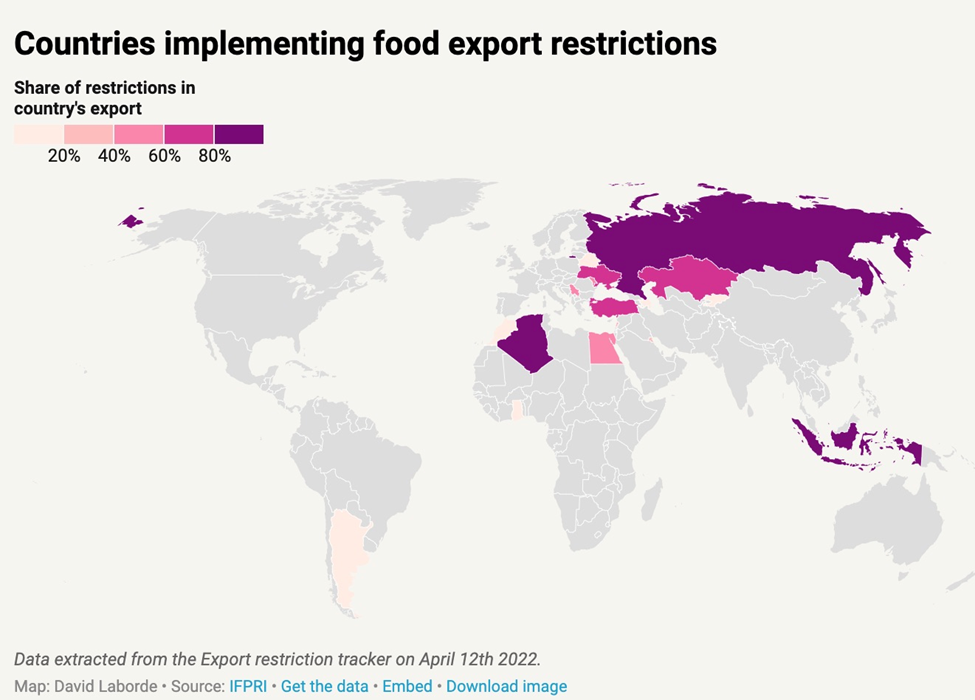

Russia’s export restrictions on wheat predate the war and include a floating export tax and export quota.

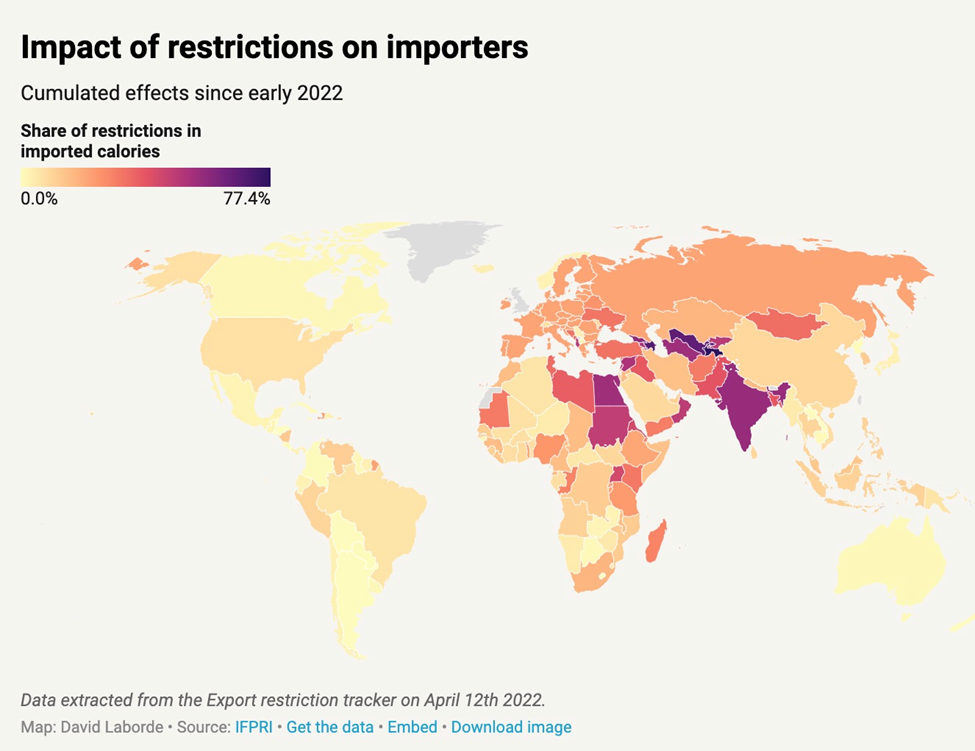

Since the Russian invasion on Feb. 24, the number of countries imposing export restrictions on food has grown from three to 16, as of early April. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) notable suppliers include Indonesia (ban on palm oil exports), Argentina (ban on beef exports), and Turkey, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan (bans on a variety of grain products). Hungary banned grain exports and Serbia halted exports of wheat, corn, flour and cooking oil.

The products most impacted by the war are wheat, representing 31% of imported calories, palm oil (28.5%), corn (12.2%), sunflower oil (10.6%) and soybean oil (5.6%).

Hardship will fall on countries most dependent on Russia and Ukraine for food imports. This includes Central Asian countries like Mongolia, and North African nations such as Sudan and Egypt, who buy a lot of wheat and corn from the region. Export restrictions on palm and sunflower oils are expected to hit Pakistan and Bangladesh hard.

The conflict has reportedly propelled prices for palm oil — ubiquitous in African dishes — to record highs, even though neither Russia nor Ukraine produces the tropical commodity.

As stated by IFPRI, export restrictions during 2007-2008 food price crisis suggests that such policies contributed to 40% of the increase in agricultural prices over the period.

Data from the United Nations shows world food prices reached an all-time high in February — a year on year increase of 20.7% — driven by an 8.5% increase in the FAO Vegetable Oils Price Index, which also hit a new pinnacle.

The Food Price Index continues to climb, registering 157.48 in March, which is 36.5% higher than a year ago.

In the United States (and Canada), skyrocketing food inflation is a gut punch to the nation. The economic recovery from the pandemic created the worst supply-chain crisis in modern times, with demand outstripping supply for hundreds of items. The Russia-Ukraine war and other “black swan” events such as bird flu are further gumming up supply chains.

Canned pet food, cheap sources of chicken and turkey, baby formula and cooking oil, are among the grocery items seeing chronic shortages.

According to one commentary,

Unfortunately, more global difficulties are coming. There will be more war, there will be more pestilences, there will be more natural disasters, and even the United Nations is admitting that we are heading into the worst global food crisis since World War II. So if you think that global supply chain problems are severe now, just wait until you see what is coming next.

Consider: Russia and Ukraine supply 30% of the world’s wheat, and we were already facing a global food crisis before the war.

Food insecurity has doubled in the past two years, and the World Food Program estimates 45 million people are on the brink of famine.

When US Senator Roger Marshall was recently asked about this, he stated that a “world-wide famine” is definitely going to happen:

“Did you just say there will be a famine in Europe in the next two years?” host Maria Bartiromo asked.

“This will be a worldwide famine. I think it will be even worse next year than this year. So if 12, 15% of the wheat comes from Ukraine that’s exported, and they’re having problems getting fertilizer, they’re having tractors in the field, all the diesel fuel is going towards their war efforts, right?” the senator said.

Spheres of influence

Recall what happened during covid with supply disruptions of PPE. Frustrated by dangerous shortages of masks, gloves, gowns and ventilators — much of this essential gear comes from China — countries started making their own personal protective equipment.

This is a good example of how the world is changing with respect to globalization. Countries are becoming more protectionist, as they realize they can no longer depend on the free flow of goods and the trust of their trading partners. President Trump made trade fairness a hallmark of his administration, imposing a series of tariffs on China, Mexico, Canada, the European Union and others, on the grounds that they would benefit US manufacturing, give the United States leverage to negotiate with other countries, and were necessary to protect American national security.

We’ve seen how the war in Ukraine has caused some countries to restrict their food exports, keeping it for their own citizens amid the prospect of higher prices and shortages.

The global population is increasing by over 75 million people a year. Impacts from weather and natural disasters will ebb and flow but population growth is a constant driver of demand. Many people in developing economies have increasing discretionary income, they are becoming richer. As income increases people move up the protein ladder, from staples such as rice they climb the ladder and demand more protein in the form of meat and dairy.

Resource nationalism regarding metals is happening in Chile and Peru, but they aren’t the only countries demanding a greater share of mineral wealth.

Zambia made it into Maplecroft’s top riskiest places to mine in due to an attempted liquidation of Konkola Copper Mines, whereas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the government in 2018 raised taxes on mining firms and increased royalties. The country is Africa’s biggest producer of copper and cobalt.

Indonesia has banned a number of unprocessed ore exports including nickel, tin and copper in a bid to encourage a domestic electric vehicle supply chain.

Even the United States is getting into the act. Last September a congressional committee added language that would set an 8% gross royalty on existing mines and 4% on new ones.

There would also be a 7-cent fee on every ton of rock moved. According to a Reuters story the proposal would mark one of the most-substantial changes to the law that has governed U.S. mining since 1872 and could raise about $2 billion over 10 years for federal coffers…

Meanwhile the supply chain disruptions wrought by covid continue to worsen — further casting doubt on the reliability of global trade. Nearly a third of goods leaving the Port of Shanghai are reportedly held up due to strict lockdowns in the city of 26 million, meaning further delays and shortages of electronics in Europe and the United States.

The capital Beijing is now on high alert for a potential lockdown, with residents stockpiling supplies after authorities ordered 20 million people to take mandatory tests this week. One woman told the Wall Street Journal she had purchased a freezer over the weekend and filled it with enough to feed her family of five for three months.

Between covid, the war in Ukraine, climate change, the rise of trade protectionism, and populist nationalism (not only Trump but the far-right in Europe), we’ve come a long way from the heady days of globalization, when goods flowed unimpeded across land and sea, trading partners were friends, and countries respected borders.

A 2019 article in Arab News asked whether, with US interest in playing its traditional global role fading, the world is experiencing a transition to a new world order based on great power competition and spheres of influence. We would answer that question in the affirmative.

Even before the war made clear President Vladimir Putin’s intentions of carving a deep sphere of influence in Central Asia, through an audacious attempt to bring the entire neighboring country of Ukraine under Russian control, the global order was under pressure.

The American public was growing weary with the responsibilities that come with global leadership, especially its entanglements in the Middle East. Russia tried to take advantage of US weakness, by backing Syria, annexing Crimea and invading Ukraine (the first time, in 2014) and Georgia. China was building up its military and taking actions to reinforce its claims in the South China Sea, however unpopular with its neighbors and the top cop in the region, the US Navy. Through its Belt and Road Initiative and a mixture of economic, diplomatic and military might, China was gaining greater influence in parts of Asia.

It’s not quite ‘1984’, George Orwell’s seminal work describing how the spoils of the world were divided among three warring superpowers, whose struggle for global dominance plunges the globe into endless conflict, but everything appears to be heading away from globalization.

Conclusion

Coming full circle, what does this mean for emerging economies intent on funding large infrastructure spending commitments by taking out loans in their own currencies and paying back the interest by printing money, as Modern Monetary Theory implies?

Well, I believe that in the future, once China has proven it’s possible to do this, other countries will catch on and follow their lead. Up to now, countries are more or less forced to out-export each other because they need the hard currency (mostly dollars) to buy commodities.

With MMT-inspired spending, they will no longer have to do this. Using their sovereign currencies, countries would trade with each other within their zones of influence. Each produces the goods and services they are best at, and sells into the region. This is the economic model China envisions through its Belt and Road Initiative. BRI members essentially become client states of China, whose huge marketplace provides opportunities for them to grow their economies. China gets access to cheap resources and cheap labor.

We see the same thing happening in Central Asia, where former Soviet bloc countries trade among each other using the rouble, in exchange for accepting the protection of Mother Russia.

There is already a North American trading bloc in NAFTA, renamed the cumbersome United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

We can claim some legitimacy to this idea of spheres of influence. Esteemed Harvard professor Graham Allison wrote about it in a 2020 Foreign Affairs’ commentary. The piece was entitled ‘The New Spheres of Influence: Sharing the Globe with Other Great Powers’. In it, Allison writes, Going forward, U.S. policymakers will have to abandon unattainable aspirations for the worlds they dreamed of and accept the fact that spheres of influence will remain a central feature of geopolitics.

Arguably, the new world order will feature independence, not interdependence. The idea is to make each country strong, self-sufficient, and reliant only on its neighbors, not the rest of the world.

Using MMT as a model, countries could roll out expansive infrastructure programs that will require vast amounts of raw materials. But if the commodities are purchased with their own (or the sphere’s) currency, they will no longer go massively in debt by having to convert funds to US dollars. They can simply buy the goods and pay the interest on their loans using their own currency.

Of course, there are downsides. One being the hoarding of resources, as countries practice resource nationalism to ensure that outsiders are not allowed to plunder their best crops, minerals deposits, oil & gas reserves, land and water. Capital controls would have to be imposed, limiting the ability of citizens to buy foreign assets and of foreigners to buy domestic assets.

On balance though, it’s a brilliant idea that, if it catches on, could fuel the next commodities boom, rivaling nothing we’ve ever seen before.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments