Mining industry dogged by retirements and lack of new recruits

One of the biggest challenges facing the mining industry is a growing skills gap created by an aging workforce and a dearth of talent waiting next in line.

According to Walter Copan, vice president, research and technology transfer at the Colorado School of Mines, the industry is facing a critical skills gap, compounded by the so-called ‘grey tsunami’, referring to the amount of retirements anticipated.

A study put out by Deloitte last year revealed that nearly 50% of mining engineers will reach retirement age within the next decade. The average age of a US mine worker is 46.

British mining also faces a big challenge to meet its needs, according to Rhys Morgan, an engineering and education director at the Royal Academy of Engineering. Some 80% of the 1,250 mining engineers registered with the UK’s Engineering Council are over 50, and 40% are at least 60, he said.

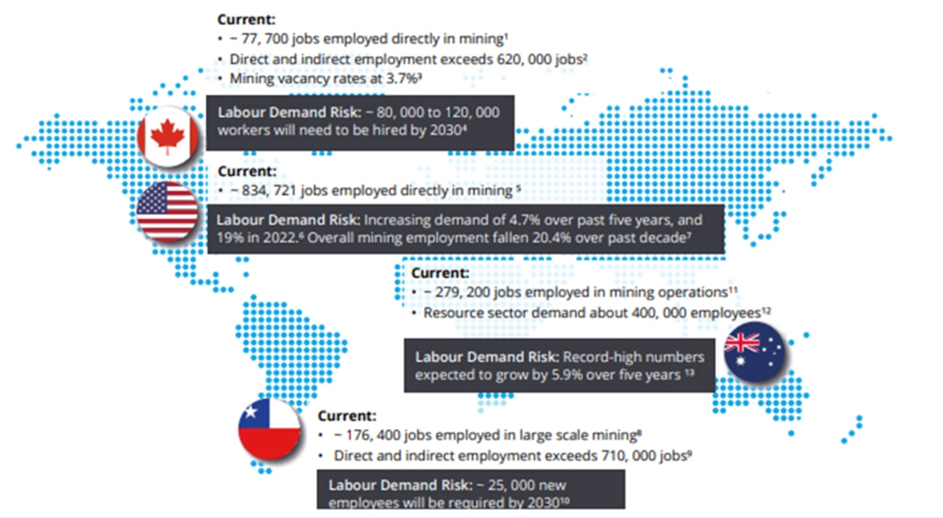

The Deloitte study found that mining employment has fallen 20.4% over the past decade in the United States. In Canada, approximately 80,000 to 120,000 workers will need to be hired by 2030.

The firm highlighted the danger of critical knowledge and skills being lost, when they are needed most, as demand for metals surges for the transition from fossil-fueled to renewable energy, and electrification.

The study also said many jobs are likely to be reshaped by technology over the next decade, “In particular, the use of remote operations centers or ‘nerve centers’ is creating new roles, such as nerve center orchestrators and data scientists, integrated master schedulers, and team performance scientists.”

A McKinsey survey found 71% of mining executives are finding a talent shortage is holding them back from delivering on production targets and strategic objectives. 86% say it’s harder to recruit and retain talent, particularly in specialized fields such as mine planning, process engineering, and digital (data science and automation).

A recent PwC study found that nearly two-thirds of CEOs believe skill shortages will have a large or very large impact on profitability over the next decade. 57% of CEOs who responded see recruitment as the biggest barrier to adopting new technology.

In Australia, the number of mining job vacancies rose to 11,700 in May 2023, over four times higher than the 2,500 in May 2016. In Canada, the job vacancy rate was 4.6% in June 2023 compared to 2.4% in 2018. In the US, it was 5.1% for mining and logging, versus 3.6% five years earlier.

The Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration (SME), via The Oregon Group, says the mining industry expects to add 11,0000 to 13,000 jobs per year over the next 20 years. For example in April 2023, the US mining sector had 36,000 job vacancies, up from 27,000 in 2022.

“Mining, mineral processing and then the downstream production of the materials that we rely upon for all aspects of the energy sector [are] at risk because of these shortages, and I find the statistic staggering that we are anticipating a retirement of more than half of the US mining workforce over the next six years, that’s 221,000 workers that are expected to retire by 2029,” Copan said in a June testimony before the House Committee on Natural Resources.

And this just in from Chile: the world’s top copper producer and second-largest lithium miner will need more than 34,000 new workers by 2032.

The report by the CCM-Eleva Alliance, a joint initiative between the Mining Council and Fundacion Chile, analyzed workforce trends and challenges of 27 mining and supplier companies.

Program Director Vladimir Glasinovic said, “The fresh estimation of talents needed in the next decade reflects a growth of 36% compared to what was estimated in the previous study.”

One of its main findings was the demand for human capital — contrary to the expected consequences of automation — will increase by more than a third over the next nine years. Driving this demand for workers are retirements, and the development of new projects, such as Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca 2 (QB2), a copper mine expansion.

Three-quarters of the demand for professionals will be concentrated in five types of specialists. Mechanical maintainers topped the list, followed by mobile equipment operators and fixed equipment operators.

Younger generation

The bigger problem for the industry though, is a shortage of new talent to replace the old when the time comes. According to Copan, the pipeline of people servicing the sector, from the leadership level to engineers, metallurgists and geologists, are being replaced only at a trickle in the United States, Canada, Australia and Europe.

Part of the problem has to do with declining enrolment in post-secondary programs related to mining, engineering, and extractive metallurgy. The other issue is mining itself, not considered an aspirational industry by younger people raised on environmental awareness and a different set of work values.

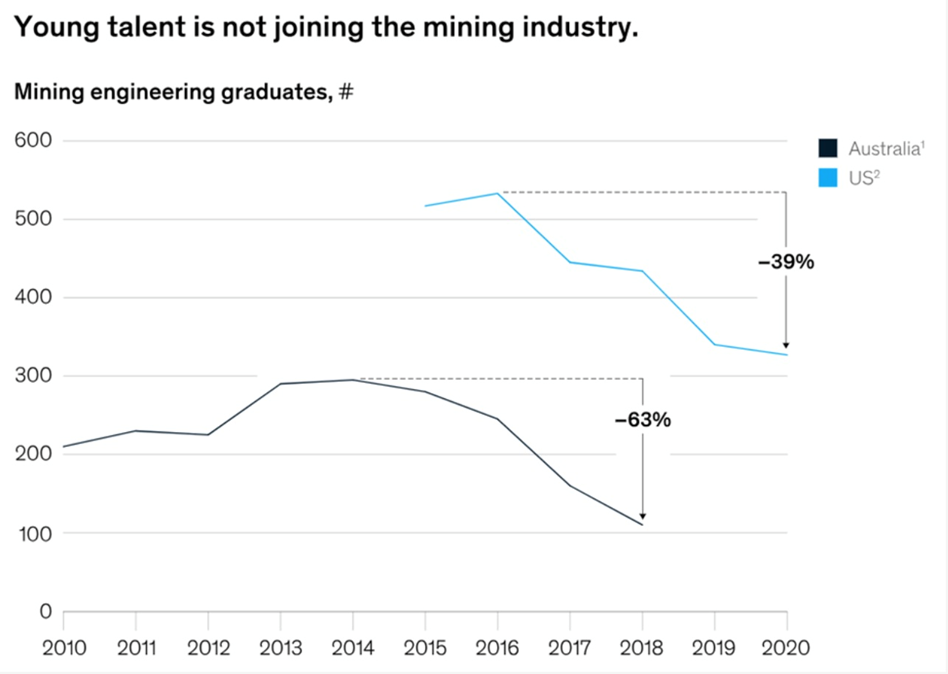

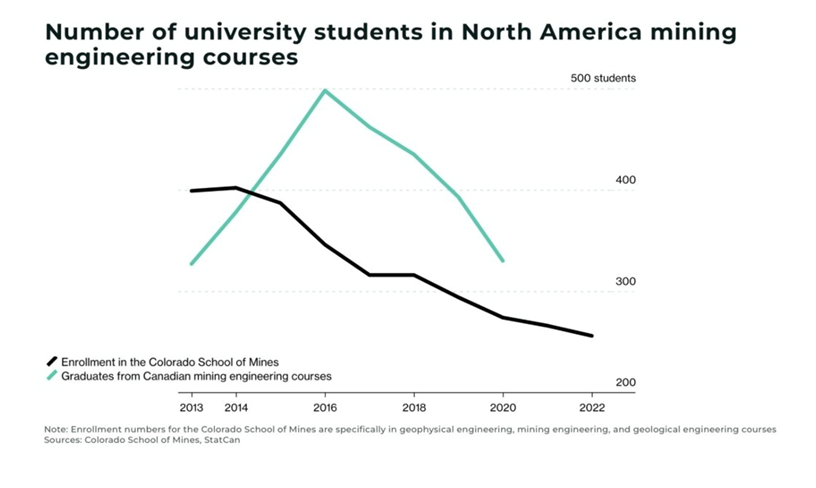

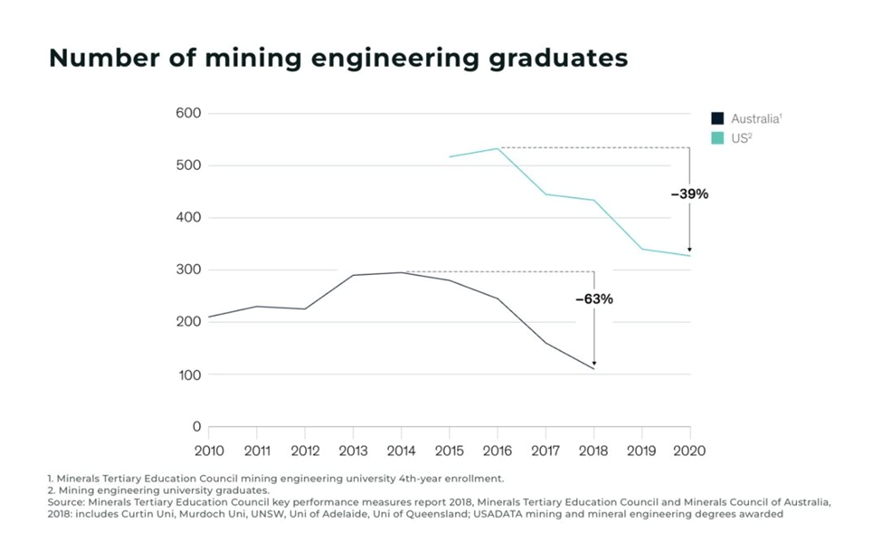

At the Colorado School of Mines, enrolment in mining, geophysical and geological engineering undergraduate degree courses in 2022 was down about 35% from almost a decade ago. Nation-wide, 314 mining and mining engineering degrees were awarded in 2021, a decrease of 3.98% compared to 2020.

In Canada, the number of these graduates dropped by a third between 2016 and 2020, says Statistics Canada.

There has been a whopping 39% decline in mining graduations in the United States since 2016. In Australia, mining engineering enrolment has fallen by around 63% since 2014.

According to The Oregon Group, federal funding for mining schools was cut drastically after the Federal Bureau of Mines was dissolved in 1996. The number of mining and mining engineering programs at US colleges and universities went from a high of 25 in 1982 to 15 in 2023.

Last year, senators Joe Manchin and John Barrasso introduced the Mining Schools Act to establish a $10 million grant program for mining schools to fund recruitment.

Source: Colorado School of Mines, StatsCan

Source: Minerals Tertiary Education Council

“There’s been a bit of a lost decade in people going through university in mining courses — that’s proving to really come to crunch point now,” said Alison Allen, deputy managing director at UK-based mining consultancy Wardell Armstrong. “There are too few graduates filling needs.”

At the UK’s prestigious Camborne School of Mines, traditionally an important feeder school for the industry, the number earning degrees from its undergraduate mining engineering course has fallen in recent years, with new intakes halted in 2020.

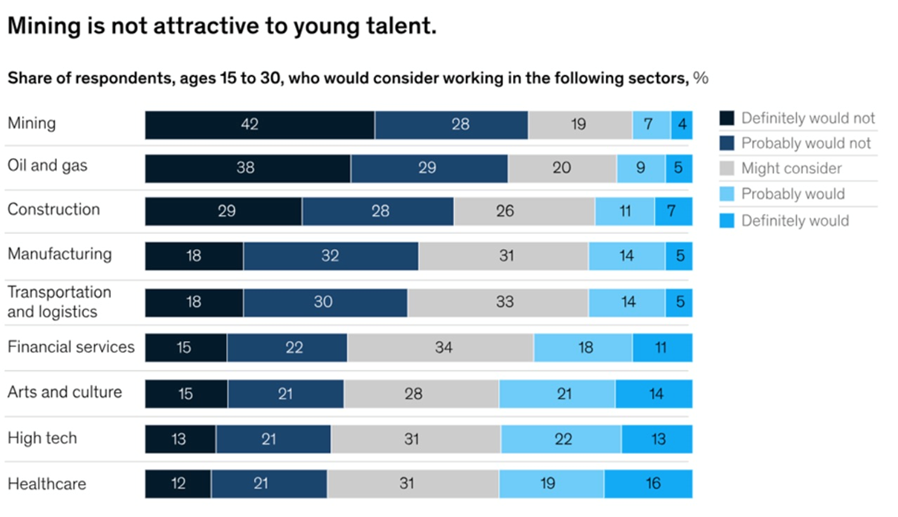

The above-mentioned McKinsey survey reported that 70% of 15 to 30-year-olds said they “definitely wouldn’t” or “probably wouldn’t” work in mining. Only 4% said they “definitely would”.

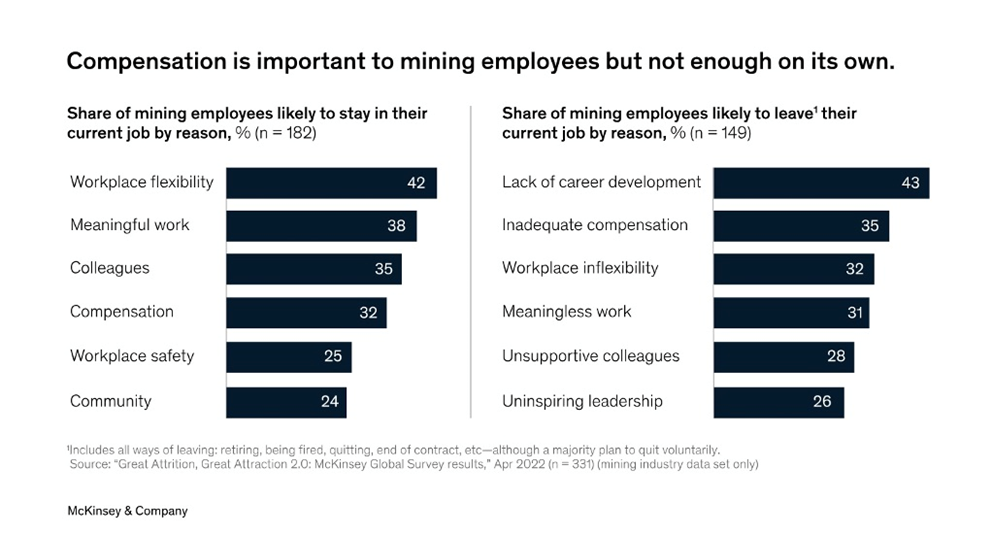

Compensation was previously the key factor in attracting talent, with mining paying an average salary of US$115,761, versus the national average of $59,428.

But today’s graduates want more than a fat paycheck.

“They tell us: ‘You can try and throw as much money as you want at me, but that’s not going to attract me,” an anonymous mining executive said in a recent EY report.

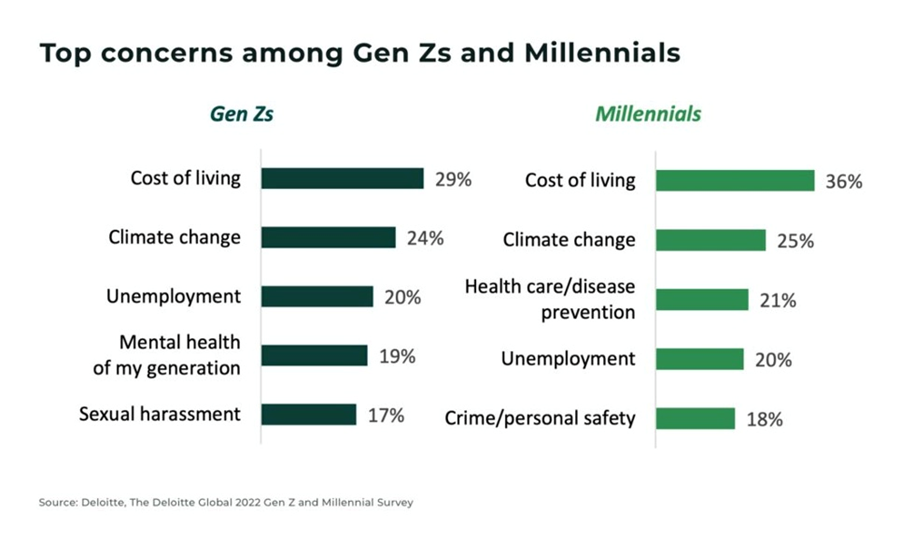

The Oregon Group explains that employment expectations among the new generation, Gen Z and Millennials, have shifted significantly, with greater emphasis on meaningful work, work-life balance, remote working, job security, a sense of belonging and feeling valued.

In a BDO survey of Gen Z, 66% of respondents said having a career that positively impacts local communities is important to them, and 59% said positively impacting the environment is important.

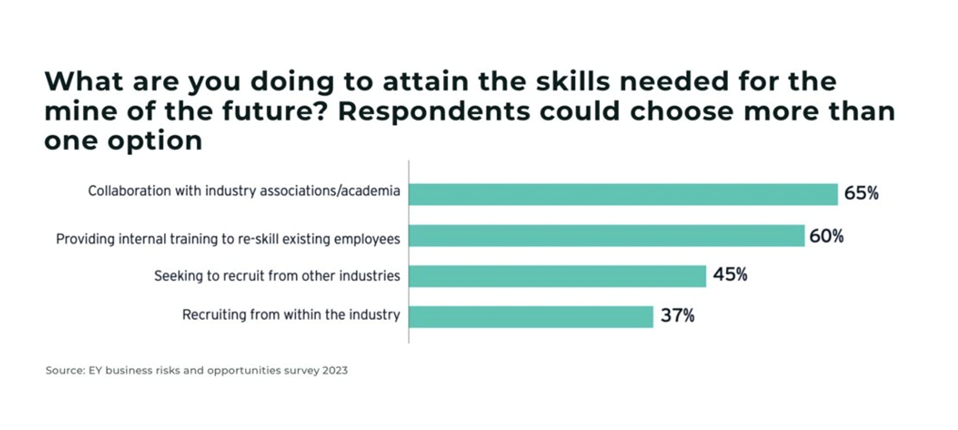

As noted in a 2023 Bloomberg article, fewer students now want to be geologists or engineers, partly due to mining’s negative image regarding pollution, human rights and gender equality. That’s leaving the industry with an aging workforce and forcing it to recruit from outside the traditional university talent pool, such as through apprenticeship programs and internal training.

In the United States, registered apprenticeships in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction more than doubled from 411 in 2020 to 1,065 in 2021.

in Australia, 7,689 apprentices and trainees joined the mining workforce in 2022, an increase of 19% on 2021, states The Oregon Group, adding that BHP has announced a plan to hire 3,500 new apprenticeships and trainees, as part of a US$800 million plan to “create a pipeline of future talent in highly skilled roles”.

The McKinsey report suggests the mining industry is partly to blame for failing to adapt to new workforce realities, and notes the industry faces several structural challenges. This includes lack of sophisticated infrastructure (hospitals, schools, entertainment) and therefore lower family friendliness. Equally, there is the perception that the work is physically demanding and hazardous. Then, once talent has been attracted and employed, additional pain points often include uninspiring capability development (beyond standard occupational training), limited or vaguely defined career progression pathways beyond middle-management layers, and insufficient levels of diversity and inclusion.

Such issues have been historically associated with mining — what’s changed today, however, is that more recent macro trends have brought these challenges into sharper relief. These trends include a greater focus on challenges for minorities and women in mining, Gen Z’s expectations to have purpose at work, an increasing disconnection between what workers want and managers provide, and competition for digital and technical talent among all industries.

Consequently, the employee value proposition (EVP) in mining has started to deteriorate and this is showing up in industry data, with demand outstripping the supply of mining talent.

More positively, the organization has four suggestions for reversing the trend: treating talent as a strategic pillar, alongside safety, production, and cost; double down on what matters to employees; understand which skills matter and invest in them; and make bold moves on the social agenda.

The Oregon Group argues that in recruiting new graduates, the mining workforce is too often seen as an enabler, not a driver of value; that there is a lack of transparency over environmental, social and governance (ESG) improvements; and that the industry has failed to get its message out about the importance of mining for meeting net-zero targets en route to the global energy transition.

“As societal expectations are changing, and higher standards are placed on organisations, we must ensure that we are consistently displaying and living our values. Without change or action, our ability to attract and retain partners and talented people will be negatively impacted. The trust from host communities and countries may also be weakened, limiting our operating licence and growth opportunities” — Rio Tinto Annual Report 2022, Strategic Report

The Oregon Group also notes that artificial intelligence, or AI, offers the mining industry an opportunity for significant productivity savings, and to potentially reduce its dependence on manual labor, through automation. The shift to AI will require new skills such as coding and robotics engineering.

The above-quoted Walter Copan, of the Colorado School of Mines, sends a positive message about mining’s future through a statement in an August, 2023 article in the Canadian Mining Journal:

“I think we will have a chance to rebuild the workforce. I’m also excited about a new era of innovation for the mining sector as we look at the role [of] industrial automation, robotics and artificial intelligence,” Copan said. “We have an amazing opportunity for us to reduce collateral environmental damage from the sector through the application of advanced technologies, and I think that’s going to be an important part of [what] the investment community is looking at.”

This is a good segue into the last section of our article, on the lack of investment in mining.

Lack of investment

Despite enjoying strong balance sheets and healthy margins, the mining industry is coming off almost 10 years of underinvestment.

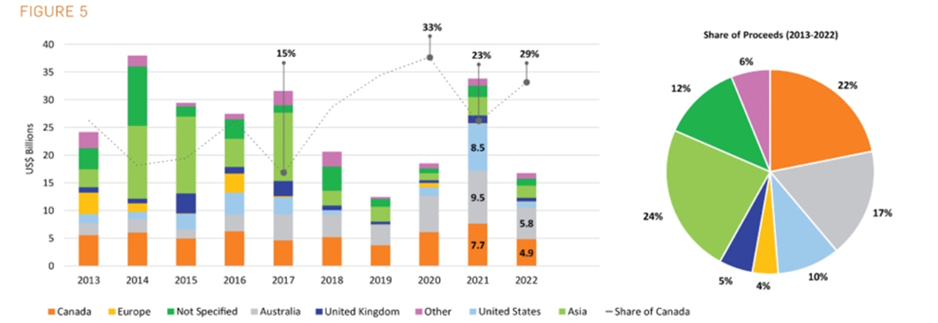

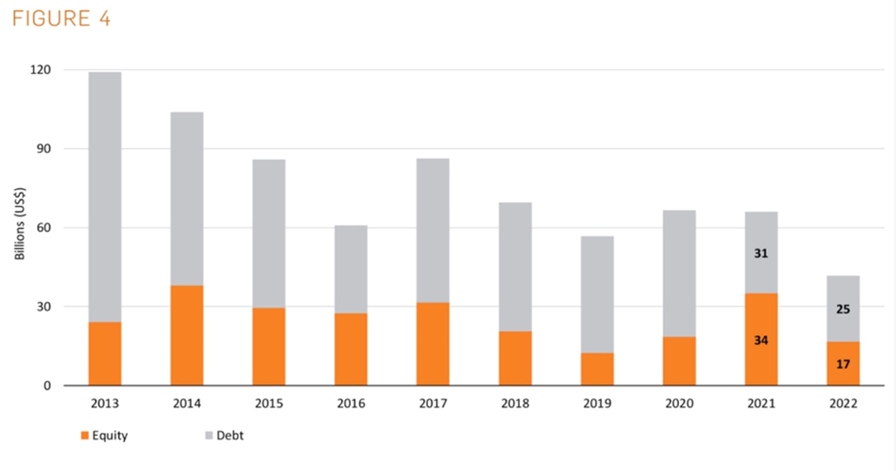

According to the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), 2022 marked a reversal of money flowing into the mining industry from virtually every source, as equity financing was down 50% from the nearly $35 billion raised in 2021. Canada is holding up better than the other major marketplaces.

In an analysis of the industry’s challenges over the next decade, McKinsey highlighted the dichotomy between the market capitalization of top mining companies, and capital spending, which is traveling in the other direction.

Globally, capital expenditures in mining fell from approximately $260 billion in 2012 to $130 billion in 2020 (corresponding to 15% and 8% of industry revenues, respectively), the consultancy found.

Although growth is again on their agendas, executive teams and boards remain cautious about using large-scale capital projects to fuel growth.

That’s due to the bust that followed the commodity boom in the early 2000s. It left many senior mining companies battered and bruised — with ensuing chief executive firings and billion-dollar write downs due to reckless acquisitions made at the top of the market. Many major mining companies thus drastically curtailed their exploration programs.

In September 2023, via Mining Engineering, McKinsey wrote that the importance of metals and minerals is evident in the rapid growth of commodity trading pools, which nearly doubled year over year, reaching close to $100 billion in 2022…

Conclusion

The mining industry right now is dealing with two problems: a lack of capital, especially on the exploration side, and a dearth of personnel, as the old guard slips into retirement and not enough new hires are coming through mining education programs to replace them.

A better job could be done of educating the younger generation and society in general of the requirement for mining in the energy transition. Without it, there literally would be no electric vehicles, no renewable energy, no industries of virtually any kind.

Yet global exploration budgets in 2021 were half of what they were in 2012, and 80% of new copper production is coming from just five mines. Two of the world’s biggest copper producers, Chile and Peru, are experiencing social unrest, and leftist regimes that want to squeeze more taxes and royalties from the global miners that operate there.

In the West, a lack of mining and exploration has left us dependent on our adversaries — China and Russia — for many critical minerals including rare earths, lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel, copper, palladium and uranium.

Other friendlier nations, like Indonesia, merely restrict the amount of metal that can be exported. The archipelago nation’s ban on nickel shipments beyond its borders is designed to create a domestic mining and mineral processing industry. Yet most of Indonesia’s nickel production is owned and paid for by China.

Many of the world’s existing mines are being depleted, meaning operations have to move from surface to underground, or the orebody expanded laterally. Both involve huge extra expense. Ore grades too are falling, which means the cost of mining increases, as it requires more earthmoving to get smaller amounts of ore.

How to avert the impending metals supply crisis? More investment from the majors into the junior resource companies that actually go out and do the exploration would help — either through acquisitions, or the purchase of mining properties under development.

Institutional investors such as large banks and hedge funds used to invest in small mining companies, but many have exited the sector in pursuit of less risky propositions. The retail investor has all but fled the industry, due to losses incurred from the last downturn or aging out of the space. The investors replacing them have no knowledge of how to make money in junior mining, they don’t “get” gold, or they invest in sectors they understand, like tech and cryptocurrencies.

Amid the bleak mining landscape, however, there are shoots of green. Discoveries are being made, and the majors are still putting money into juniors, albeit few and far between. Barrick Gold’s $23.4 million investment in Hercules Silver is one example. Snowline Gold made two significant discoveries in the Yukon, including the Valley zone on their Rogue project, a near-surface, high-grade, bulk tonnage gold system.

New talent can be coaxed into the industry if mining companies embrace technology and begin adding the new jobs that come with it. There are opportunities in industrial automation, robotics and artificial intelligence, for example.

Changing the mining culture to align more with the younger generation’s values is a bigger challenge that will take time to address.

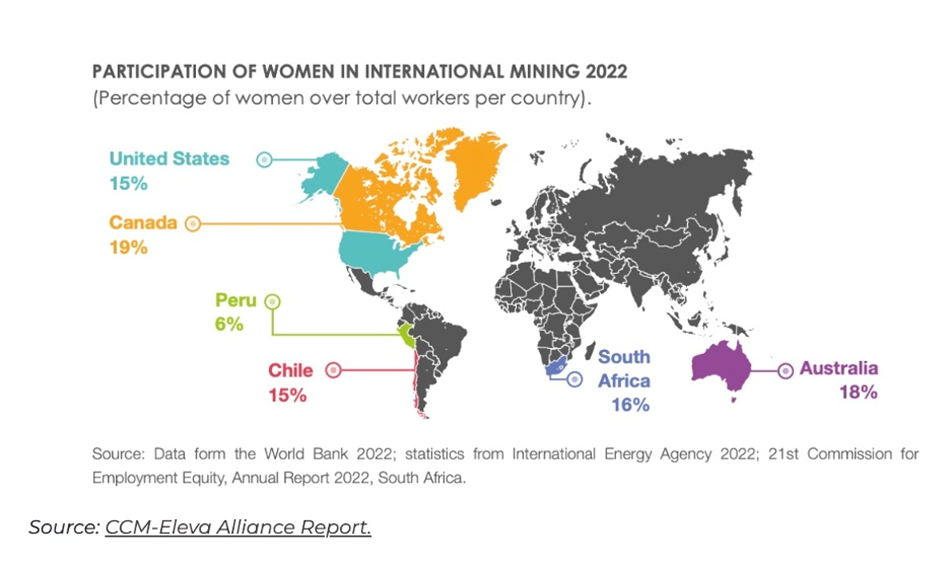

One area that seems to be improving is the number of women in mining. The above-mentioned report on Chile, by the CCM-Aleva Alliance, concluded that female participation in the industry is at 15%, where one in every three hires was a woman. Participation in decision-making decisions reached 17%. The country is better positioned in terms of women’s participation in the mining industry than Peru, and at the same level as the United States (see figure below).

McKinsey said multiple mining companies have boosted the proportion of women they employ. BHP increased their female payroll from about 21% to 32% from 2017 to 2022, Teck from 17% to 24%, and Anglo American from 19% to 24%.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

John

Interested to join your team..to be a driver