Miners find out the hard way why cobalt is called the goblin

Cobalt, a semi-rare metal that derives its name from the German word for goblin, was given its moniker by medieval miners who frequently came across its noxious ores in their hunt for silver and gold. After a 50% drop in prices this year, it’s turned toxic for Glencore Plc too.

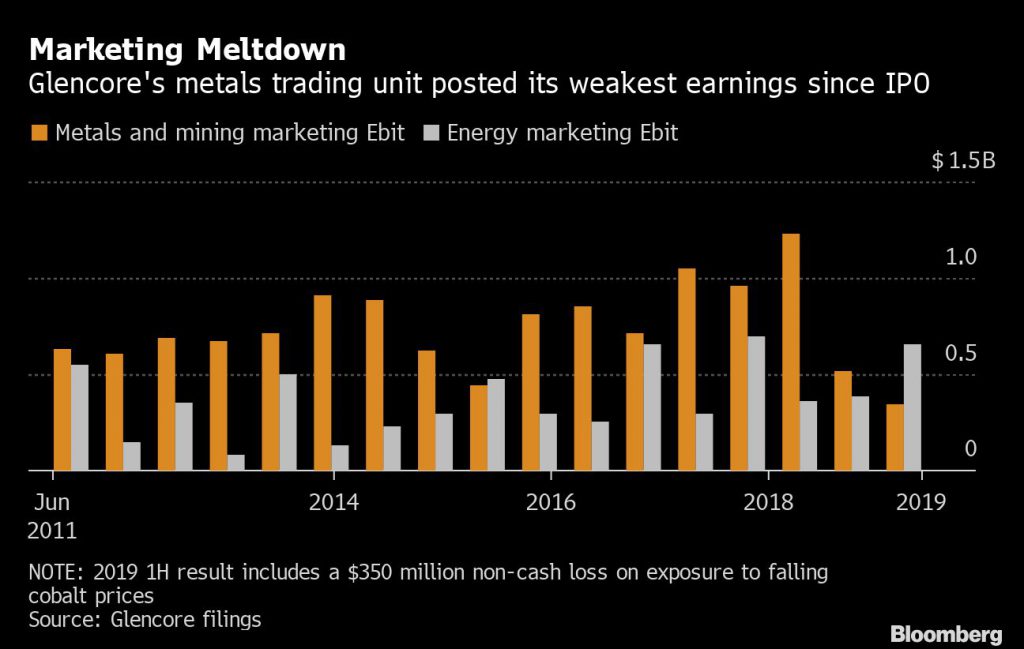

After reporting the worst financial results in three years, the world’s biggest commodities trader is shutting its Mutanda copper and cobalt mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The move will remove about a fifth of global cobalt supply and send shockwaves through a market that’s awash with unsold metal, much of it in Glencore’s hands.

“The cobalt price today isn’t helping us, so why rush it?” Glencore chief Ivan Glasenberg said as the company reported earnings on Wednesday. “The only thing you can do that’s under your control is shut or reduce tonnages.”

While cutting back production when prices are low seems like an obvious strategy, it’s one that most companies are loath to try. Glencore and De Beers are the only mining majors with a track record of actively controlling their operations to pull a market out of oversupply. For other raw materials, like iron ore, the decision to keep resources in the ground is usually seen as a recipe to handing your competitors a bigger slice of the market.

The last time Glasenberg made a big cut to production was in late 2015, when the company slashed zinc output as prices were tanking. That maneuver helped create shortages and zinc prices surged 60% in 2016.

Shares in Chinese cobalt companies rallied on Wednesday as traders bet they’ll benefit from the higher prices caused by Glencore’s cutbacks. China Molybdenum Co., which also mines in Congo, rose the most in four years in Hong Kong.

For Glencore, the precipitous fall in cobalt is more bruising because the metal, a key ingredient for batteries, was its shining star back in 2017. The miner made its copper and cobalt assets a big part of its selling pitch to investors, touting the future boom in electric cars and global urbanization.

But the strategy hit pitfalls. Excess supply has overwhelmed demand for battery materials and because it’s a niche market, Glencore hasn’t been able to hedge its exposure to cobalt, leaving the metals trading business exposed to losses. To make matters worse, Glencore detected uranium in some cobalt last year, rendering it unsaleable.

To be sure, Glencore isn’t giving up on Mutanda entirely. It expects to bring it back online in 2021 and is looking at a new mine plan that could boost production over the long term. The restart might coincide with electric cars becoming more popular with consumers, which would boost demand.

That could leave Glencore’s traders on a strong footing as they negotiate supply deals with customers who pulled out of contracts when prices were weak. “People who have reneged on us in the past, of course they’re not going to be top of our list,” Glasenberg said.

Closing the mine is an easy decision to defend when it’s not making money, but it may get harder to justify if prices rebound, said Colin Hamilton, managing director for commodities research at BMO Capital Markets Ltd. Mutanda produced about 27,000 tons of cobalt last year out of a global total of around 135,000 tons, according to trading firm Darton Commodities.

“We’re not being OPEC. We’ve got an operation that wasn’t making money at these levels,” Glasenberg said. “You’re not going to run an operation that’s not making money.”

(By Mark Burton and Thomas Biesheuvel)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments