Mine workers demanded more protection before deadly Burkina Faso attack

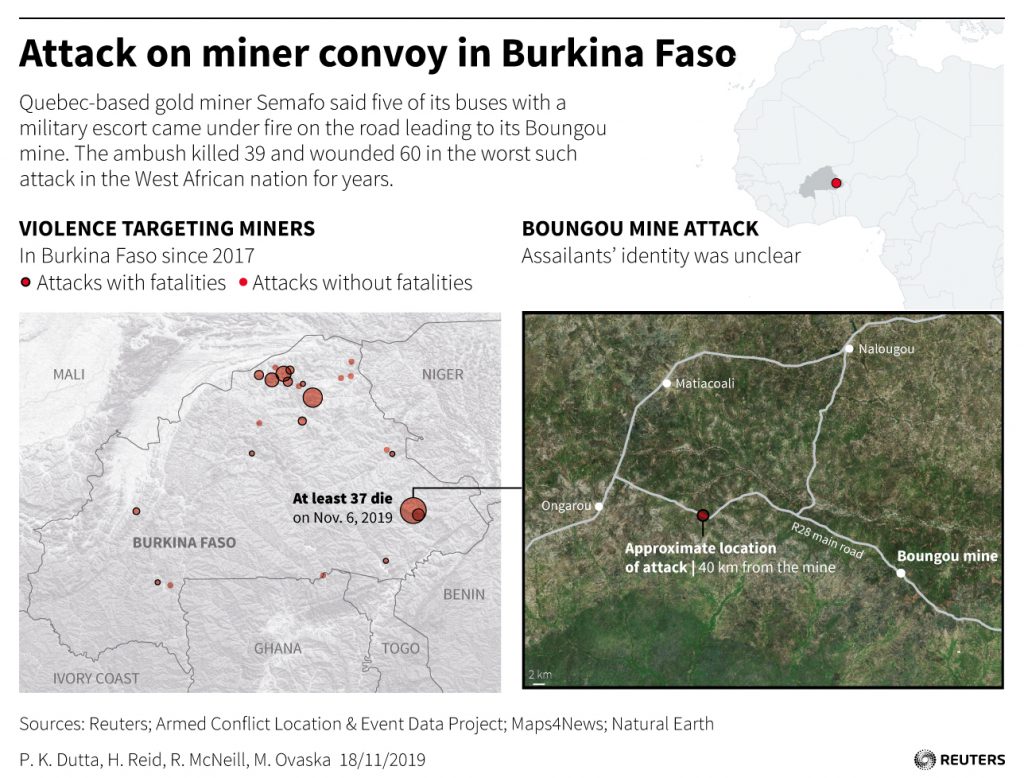

Five months before an ambush killed 39 colleagues, local workers at a Canadian-owned gold mine in Burkina Faso pleaded with managers to fly them to the site rather than go by a road that was prone to attacks, two people present at the meeting said.

The employees wanted the same protections as expatriate staff who had been flying to the mine in helicopters since three workers were killed in two earlier attacks in August 2018.

“The scale and focus of the attack was unprecedented and not seen before in this region”

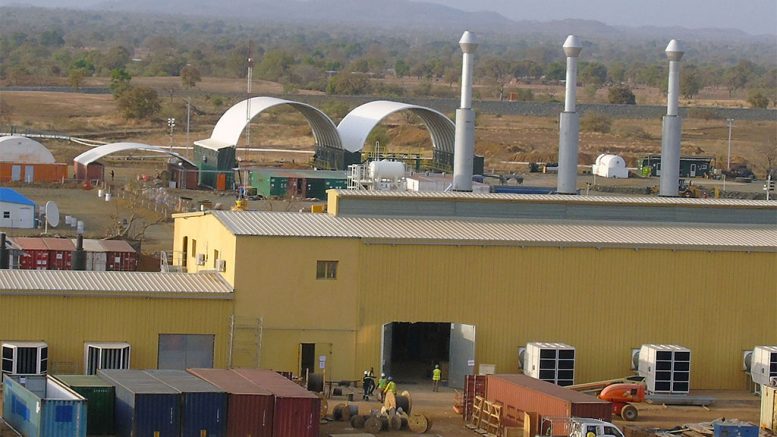

Shortly after those deaths, the mine’s owner, Quebec-based Semafo Inc. (SMF.TO), said it had added a military escort to bus convoys taken by Burkinabe workers to the site each week.

But local employees of Semafo and its Accra-based contractor African Mining Services (AMS) did not think it was enough in an area notorious for bandits and jihadists.

On Nov. 6, attackers blew up an armored vehicle escorting the workers’ convoy and opened fire on their buses, killing 39 people and wounding 60 others. It was the worst attack the West African country has seen in years.

The local employees at AMS expressed their fears at a June meeting attended by four miners representing the local workforce, an AMS manager and two AMS human resources representatives, according to two workers who attended.

“I said ‘do you want them to kill us before you take action?’,” said Samuel Kabre, who was at the meeting. “They (AMS management) said locals weren’t the target, but we were the target.”

The second source, who no longer works at the mine, declined to be named.

AMS and its parent company, Australia-based Perenti Global Ltd. (PRN.AX), did not comment on the meeting, or whether employees’ concerns were relayed to Semafo. Semafo did not have a representative at the meeting, the sources said.

In a statement responding to questions from Reuters, Perenti said that according to its intelligence, military and government personnel were considered the likely target of armed raids, not local workers.

It said that security matched the level of threat identified by intelligence sources and international security firms.

“The scale and focus of the attack was unprecedented and not seen before in this region.”

Semafo representatives did not respond to calls and questions delivered to the company’s offices in Ouagadougou and its Montreal headquarters.

A representative with law firm McMillan LLP Inc., which is listed in past security filings as counsel for Semafo, referred questions to the company.

Body armour left unused

AMS hired mining consultant Patrick Hickey in March to draw up a proposal to fly all staff to and from the mine once a runway had been built there, Hickey told Reuters.

On June 13, he sent his proposal to officials at Perenti, which was then called Ausdrill, according to an email seen by Reuters.

John Kavanagh, AMS’ former chief operating officer of African operations, presented the plan to Semafo soon afterwards, according to Hickey, who said he was not privy to Semafo’s response.

“Things were changing, and more and more we were going to have to fly employees out in Burkina. Not everyone had come to terms with that yet,” Hickey said.

Kavanagh did not respond to calls and an email seeking comment. Perenti and AMS declined to comment on Hickey’s plan, if it was shared with Semafo or what the Canadian company’s response was.

Around the time of the June meeting, Perenti sent bullet-proof vests for Burkinabe workers to wear on the journey to and from the mine, Kabre and his former colleague said. Perenti confirmed that body armor was offered to staff.

But workers refused to wear it, fearing the expensive kit would attract armed assailants seeking to steal it. The unused vests are piled up in an office at the mine, they said.

No one has claimed responsibility for the attack and Burkina Faso’s President Roch Marc Kabore has referred to the assailants as unidentified “terrorist groups”.

Groups with links to Islamic State and al Qaeda operate in the country and have carried out similar attacks over the past year, security officials in the region have said.

Contrasting plans

After the ambush, Semafo suspended operations at the mine in Burkina Faso’s Est region and said it would not resume them until security in the area was assured.

The company had this year started building an airstrip to increase transport capacity at the site. But initial plans included flying only expatriate employees and some high-level local staff, according to company documents and a former Semafo employee.

A PowerPoint presentation prepared by Semafo in early May and seen by Reuters shows that the runway would be used by a single-pilot Cessna Grand Caravan plane that could hold 9-12 passengers.

That plane was suitable only for flying a small number of employees, not a workforce of hundreds, said the former Semafo employee. “You would need to add additional planes.”

At the time, the company intended to fly the plane three times a week, the source said. He did not know if the plan had been altered since May.

AMS and Perenti declined to say whether they supported Hickey’s proposal to fly all employees.

His plan called for two Beech 1900D propeller planes and a crew of four pilots to make multiple trips each week at an annual cost of between $3.4 million to $3.8 million, according to the emailed proposal seen by Reuters.

Flying only senior management and expatriate staff would cost $1.5 million to $2 million, the proposal said.

The runway was still under construction at the time of the November ambush, Kabre and the former mine employee said. It was not clear when it would be finished.

(By Edward McAllister, Jeff Lewis, Allison Martell and Helen Reid; Editing by Katharine Houreld, Alexandra Zavis and Mike Collett-White)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Eddie

4 million USD a year to save lives is nothing for a reasonable output gold mine operation, however, Burkina Faso´s government should make its job.