London Metal Exchange has to restrain disorderly copper

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

This was the week Doctor Copper turned disorderly.

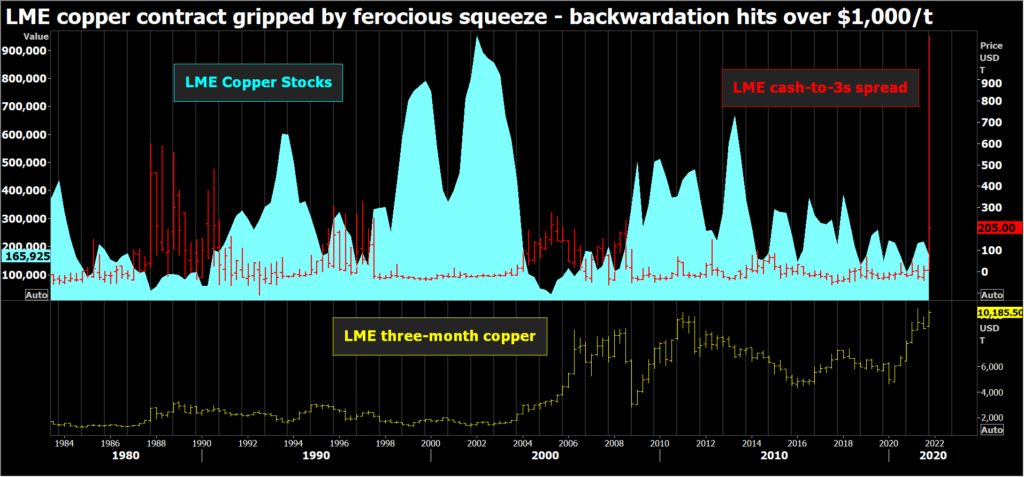

The London Metal Exchange (LME) was forced to apply the restraints as a ferocious squeeze rocked the market, with the premium for cash metal spiralling out of control to an unprecedented $1,103.50 per tonne at one stage on Monday as the exchange’s monthly prompt date descended into chaos.

The London copper contract has been sucked into a stocks vacuum after the amount of available metal in the LME’s global warehouse system sank to just 14,150 tonnes last Friday, the lowest since 1974. The rest of the 181,400 tonnes had been canceled in preparation for load-out, meaning it was off the table in terms of the monthly reconciliation of physical positions.

Related: What happens when the world’s key metal exchange has no metal?

Who’s grabbed all the copper?

Trafigura for one. The trading powerhouse said it had indeed been hoovering up LME stocks but said that others had also been involved in the string of stock cancellations that depleted available tonnage from more than 168,000 tonnes in the middle of September.

The squeeze has, inevitably, evoked bad memories for the copper market, specifically the Sumitomo scandal of the 1990s, a prolonged period of manipulation centred on rogue trader Yasuo Hamanaka.

The comparison is understandable but the current market dynamics are not those of the last decade of the twentieth century.

Trouble with tom

What hasn’t changed between then and now is the LME’s tolerance for large dominant positions, both paper and physical in the form of registered stocks.

This is historically hard-wired into the 144-year-old market’s DNA because it has always been where the world’s largest industrial metals players have conducted their business.

However, the LME’s light-touch regulation conforms to the British financial model.

The current LME rule-book, allowing dominant positions but with restrictions on how they are traded, was written by Alan Whiting, executive director of the UK Treasury’s regulation and compliance department before he was parachuted into the LME in 1997 to sort out the post-Sumitomo mess.

The downside of this approach is that the LME only intervenes when the market is on the point of breakdown, or in regulatory speak, becomes disorderly.

The chaos meter, as it were, has always been and remains the LME curiosity that is “tom-next”, which is the cost of rolling a short cash position overnight. It went supernova on Friday, trading out to $175 per tonne backwardation and hit triple figures again on Monday and Tuesday.

At which stage the LME announced it would cap the spread at 0.5% of the previous day’s cash price – around $50 per tonne – – or at 0.25% in the case of big positions amounting to more than 80% of available stocks.

Since available stocks, currently negligible, are the criteria for determining dominant long cash positions, it’s no surprise that as of Monday’s close there were five of them, two of them long to in excess of 90% of available LME stocks.

Special measures

The LME, which said it had been “monitoring the ongoing tightness in the copper market with Exchange inventories falling and nearby carries tightening”, evidently decided the chaos was only going to continue as shorts tried to roll their way out of danger.

Or rather its Special Committee did.

This body with the uninspired title was created to avoid the potential for conflicts of interest that had dogged the full LME board when it used to decide on market interventions in the pre-Sumitomo days.

Chaired by Phillip Crowson, previously a long-standing LME director, the “specials” include LME chairwoman Gay Huey Evans, who also sits on the UK Treasury board, LME Clear board member Marco Strimer, arbitration lawyer Barbara Dohmann QC and independent LME director Dr Herta Von Stiegel.

Gavin Prentice, currently chairman of the LME’s User Committee, joined the Special Committee last month, presumably to boost practitioner knowledge.

While that’s a lot of regulatory and legal firepower, it still operates within the LME’s and London’s laissez-faire market ethos.

Trouble with copper

It’s clear from both LME and Trafigura statements that the two have been in regulatory dialogue about the trader’s copper positions and its draw on exchange stocks.

Trafigura appears to satisfied LME compliance officers that it has a legitimate reason for buying so much copper from what is supposed to be the market of last resort.

Cynics will scoff at the company’s quoted claim the metal is needed to satisfy customer needs in China and Asia, but global exchange stocks of copper were just 312,200 tonnes at the end of September with Shanghai stocks sitting at a multi-year low of 43,500 tonnes.

Compare and contrast with the early 1990s copper market, when the LME warehouse system – much more geographically concentrated than it is now – held more than 600,000 tonnes at one stage. Indeed, the ballooning costs of supporting the copper price in a surplus market were what did for Sumitomo’s Hamanaka in the end.

If that sort of surplus is available today, why has it not shown up?

Backwardation is supposed to attract metal but this week’s deliveries into LME warehouses have so far amounted to a meagre 9,775 tonnes despite the biggest incentive in the market’s history.

The unwelcome possibility is that the world has run out of freely available copper. Or, if there is metal out there, it is stranded by record high freight rates, another covid-19 variant on copper crises past.

Dysfunctional supply chains

That might sound shocking but the tin market is already there, registering its own outrageous $6,500-per tonne cash-to-three-months backwardation in February due to a depleted supply chain.

European zinc smelter cutbacks are sending ripples of tightness from the physical to the LME market, where three-month metal last week hit an all-time high and spreads are also backwardated.

LME lead shouldn’t be in backwardation but it is. There’s lots and lots of lead sitting in Shanghai but super-high container rates are keeping it trapped in China.

Industrial metal supply chains are currently dysfunctional in a way that hasn’t been seen in the past because it’s the result of an unprecedented pandemic.

The world is a very different place from what it was just a couple of years ago let alone the 1990s.

Is the current dearth of LME copper a manufactured shortage or another sign of a broader supply-chain crisis?

We’re going to find out very shortly since every available tonne of copper should be heading towards an LME warehouse to capitalise on the record delivery incentive.

For now tom-next has stopped flashing red, slipping back into more orderly contango Thursday morning, suggesting the turmoil has abated.

But if exchange stocks don’t rebuild, the LME Special Committee is going to have its work cut out.

(Editing by Kirsten Donovan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

2 Comments

N G

The quoted price per tonne in the first paragraph is incorrect.

Amanda Stutt

Hi Ng, we checked, this number was quoted several times by reuters, and in the FP.