LME stocks shock sends zinc price reeling

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Zinc bulls have just received a reality check.

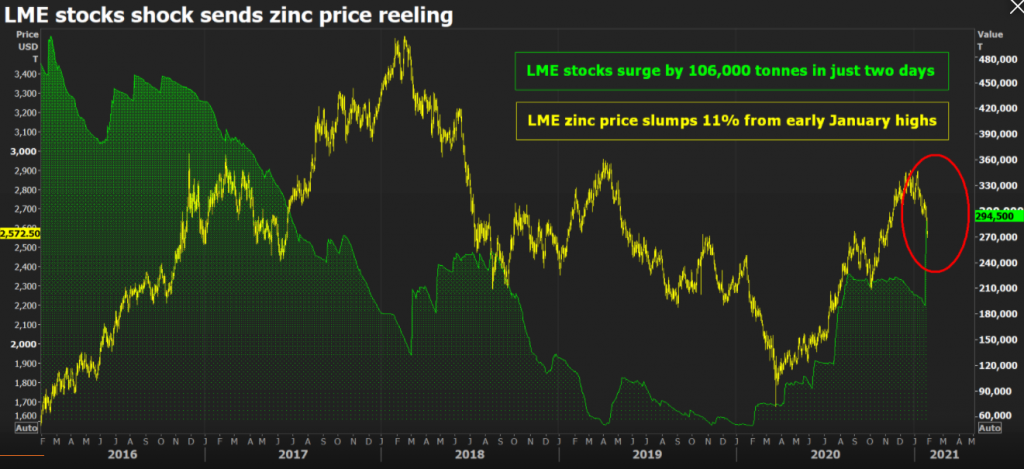

London Metal Exchange (LME) stocks of the galvanising metal surged to a three-year high of 294,500 tonnes this week thanks to the “arrival” of 106,000 tonnes in the space of just two days.

The stocks shock has transformed zinc from outperfomer to laggard of the base metals pack. At a current $2,565 per tonne, LME zinc has fallen by 11% from its early January high of $2,897.

The delivery of so much metal in such a short period of time is a bit of market theatre, which seems to have had its intended effect.

That elephant has just, partially, shown up

However, the tension between signs of market surplus and falling LME inventory had been building for some time.

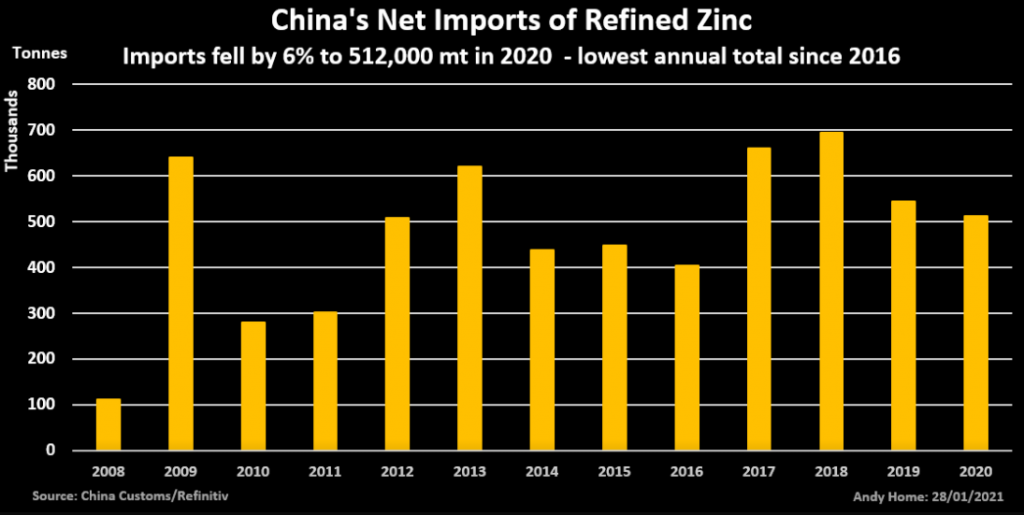

China has not come to the rescue of this particular industrial metal by hoovering up the rest of the world’s surplus metal as it has done for copper. Zinc imports actually fell last year.

Excess zinc has been steadily accumulating in the off-market shadows. Its sudden appearance has blindsided bulls trading a narrative of a raw materials crunch.

Shadow play

The global refined zinc market registered a supply deficit of 480,000 tonnes over the first ten months of 2020, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG).

Back in October the group forecast a 620,000-tonne surplus for 2020 and another hefty 463,000-tonne surplus for this year.

That’s pretty much the consensus view. Research house CRU, for example, thinks that the slump in demand due to COVID-19 restrictions led to a 500,000-tonne metal surplus outside of China last year, with a second year of excess supply expected in 2021. (“Zinc – Top 10 calls for 2021”, Jan. 27, 2021)

Even Goldman Sachs, which has been heralding the dawn of a new commodities supercycle, is cautious on zinc, “our least preferred” industrial metal.

When it comes to zinc, the super-bull bank is also with the consensus, projecting a cumulative 868,000-tonne surplus over 2020 and 2021. (“Metals Watch”, Jan. 14, 2021).

Yet this glut of metal was largely elusive last year. LME stocks rose by just 151,000 tonnes and from a very low base.

Arrivals slowed to a trickle over most of November and December and headline inventory actually fell by 10,500 tonnes over the fourth quarter.

The signs were there that metal was accumulating in the shadows. The LME’s “off-warrant” monthly report showed a 71,650-tonne build between February and November last year, centred on New Orleans, which accounted for 47,650 tonnes of this week’s inflow.

This is metal that is stored with explicit contractual reference to potential LME warranting, in effect a twilight zone between visible exchange stocks and invisible private inventory.

It’s turned out to be a useful indicator of a bigger stocks build away from the LME’s official figures.

There could be still more sitting “out there”, given the size of last year’s expected surplus.

Chinese imports fall

A key differentiator between zinc and copper is the lack of buying appetite from China despite the country’s rapid recovery from covid-19.

Net refined zinc imports fell by 6% to 512,000 tonnes last year, which was the lowest annual total since 2016.

Western surplus, in other words, has largely stayed in the West.

This is surprising since zinc is likely to have benefitted from the broader Chinese construction and infrastructure recovery momentum. It’s why it’s often traded as a ferrous derivative by locals on the Shanghai Futures Exchange.

Citi analysts expect a “deep concentrate deficit” to persist through the first half of the year

Moreover, China’s own zinc production should have been held back by a squeeze on raw materials caused by pandemic lockdowns in key supplier countries, first and foremost Peru.

Imports of Peruvian zinc concentrate averaged 70,000 tonnes in the first quarter of 2020. They almost evaporated to just 1,200 tonnes in June as multiple mines reduced operations in the second quarter.

Yet, Chinese smelters appear to have successfully compensated.

Total concentrates imports rose by 20% last year with increased supply from Australia in particular offsetting the loss of Peruvian material.

In the event, Chinese refined zinc production rose by 3.1% to a record 5.3 million tonnes in 2020, according to state researcher Antaike.

That was around 200,000 tonnes lower than originally expected but evidently more than sufficient to reduce import demand for the rest of the world’s surplus metal.

Antaike is forecasting even faster growth of 5.7% this year as concentrates supply recovers from last year’s disruption.

Still tight

China may have successfully navigated last year’s mine hits, but the concentrates market remains tight and is still a restraining influence on higher smelter utilisation rates.

Treatment charges levied by smelters for converting concentrates into metal remain at bombed-out levels below $100 per tonne, suggesting fierce competition for available material.

Everyone expects the supply chain to normalise this year, CRU for example forecasting global mine production to come roaring back with 7.5% growth after a 2.8% contraction in 2020.

The key question is how long it will take, given the potential for more disruption from second-wave pandemic lockdowns.

Citi analysts expect a “deep concentrate deficit” to persist through the first half of the year with a possible “total zinc deficit” in the first quarter, meaning the raw material deficit will be greater than the refined metal surplus. (“China Commodities Trade Data”, Jan. 26, 2021)

ING is more sanguine, looking for recovery from the second quarter onward and a resulting moderate 90,000-tonne concentrates surplus over the year as a whole. (“Zinc: Back on track after a turbulent year of mine supply,” Dec. 17, 2020)

Timing a turn in the zinc market is evidently going to be tricky and not helped by totally unexpected mine outages such as that at South Africa’s Gamsberg following a pit wall collapse.

But the market focus on a tight raw materials segment of the supply chain risks ignoring the elephant in the room, namely the large amount of metal that has accumulated outside of China over the last year.

That elephant has just, partially, shown up.

(Editing by Jan Harvey)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments