LME shines a (little) light on shadow stocks

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The London Metal Exchange’s (LME) new report on “shadow” stocks was greeted with a collective yawn by the industrial metals market.

The exchange’s attempt to throw more light on inventories “did not hold any surprises and there was not a ‘sea’ of hidden metal,” was a typical reaction from LME brokerage Kingdom Futures.

Shadow stocks of all metals totalled 1,239,556 tonnes at the end of May, equivalent to 56% of registered stocks

True, those looking for evidence of the millions of tonnes of aluminum inventory sitting outside the exchange storage system will be disappointed.

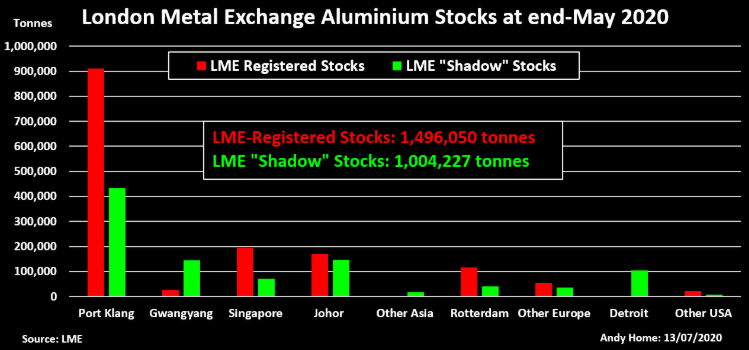

As of the end of May, there were “only” a million tonnes of aluminum lurking in the LME shadows.

But that’s still a lot of metal, given the restricted scope of the LME’s new reporting requirements.

Indeed, shadow stocks of all metals totalled 1,239,556 tonnes at the end of May, equivalent to 56% of registered stocks.

Moreover, the first four backdated reports published on Friday contain some genuinely interesting nuggets.

Making the count

There was never any prospect of the LME’s new warehouse reports, published monthly with a month’s delay, capturing the full amount of inventory sitting in the metals supply chain.

The LME has no regulatory authority to ask for, let alone publish, the size of privately-held stocks.

But it does have policing power over its registered warehouse operators and it has just extended that oversight to metal that may be one stroke of a keyboard away from hitting its system but is “invisible” to the market.

The last few years have brought about an expansion of LME look-alike storage. Stocks holders enjoy the benefits of LME warehousing, particularly the option of super-swift warranting, but at a fraction of the cost.

The flow of metal between LME official and LME “shadow” stock pools can be bewildering in a market such as aluminum because it is determined primarily by storage rather than fundamental drivers.

The LME’s reports capture only this “ready-to-warrant” material. The count is defined as metal stored under an agreement with a warehouse operator specifying it be held in an LME-registered shed, or specifying that it can be warranted at the owner’s request.

What lies beyond stays in the statistical night.

Aluminum and cooper dominate

The largest LME shadow stocks are those of aluminum, which is no surprise given it is both the largest-volume base metals market and one with a history of over-production at times of demand weakness.

And no surprise that most of the aluminum is located at Malaysia’s Port Klang, which has taken centre stage in the LME aluminum storage wars over the last couple of years.

LME shadow stocks at Port Klang were 434,000 tonnes at the end of May, compared with registered stocks of 911,000 tonnes.

Both shadow stocks and LME registered stocks of copper increased between February and May

More interesting are the shadow stocks at the South Korean port of Gwangyang and Detroit: 145,000 tonnes and 104,000 tonnes compared with registered tonnage of 22,000 tonnes and zero respectively.

Shadow stocks at Detroit rose from 67,000 tonnes to 104,000 tonnes between February and the end of May, a slightly ominous development given the amount of surplus metal that hit Motown during the last market crisis a decade ago.

None of it has yet been warranted on the LME but all of it could be, which is why it’s showing up in the new report.

The copper market, meanwhile, has taken in its stride the emergence of 161,374 tonnes of shadow stocks at the end of May.

The largest concentration is at Rotterdam, which held 89,295 tonnes, compared with registered copper inventory of 84,575 tonnes at the end of May.

It’s interesting to note that both shadow stocks and LME registered stocks of copper increased between February and May to the tune of 86,000 tonnes and 39,000 tonnes respectively.

That coincides with the first-round hit to metals demand from the fatal coronavirus.

It also highlights the potential usefulness of these new reports, given that the build in visible inventory was significantly smaller than that in previously invisible shadow inventory.

Conversely, tin’s bullish narrative appears to be reinforced by the fact that both shadow and registered stocks fell hard over the February-May period.

There were 7,500 tonnes of registered tin stocks and another 3,000 tonnes of shadow stocks at the end of February. By the end of May, these had shrunk to 2,455 tonnes and 265 tonnes respectively.

That said, such relatively low stock levels call for analytical caution, given any sizeable-tonnage movement can swing the headline pendulum.

Shadow stocks of nickel and lead were also relatively small at the end of May at 19,000 tonnes and 8,000 tonnes respectively while zinc bulls will take heart that shadow stocks were “just” 41,000 tonnes relative to official tonnage of 100,000 tonnes.

More light

The LME has successfully illuminated that part of the stocks chain which sits between the exchange’s own official system and fully off-market storage.

It has been able to do so by asserting that shadow stocks are reportable when the exchange is directly referenced in the metals storage contract.

Quite evidently, as long as a stocks owner is prepared to absorb the higher insurance and credit costs that go with fully off-market storage and has no intention of delivering to the LME, those stocks will not be captured in the reporting net.

Topping the to-do list is “transparency around bringing metal on and off warrant”

The LME has allowed stocks owners to take the initiative and volunteer information but “always expected that voluntary reporting would be unlikely to arise organically”.

With “very little” information voluntarily submitted, the exchange will exclude such stocks from its reports.

For now.

It is clear the LME is going to push further into the stocks shadows. It notes somewhat pointedly that it has “provided for additional powers in respect of promoting enhanced voluntary reporting, including financial implications for market participants who warrant metal which has not previously been voluntarily reported”.

Watch this space.

And watch the regulators.

Brussels in particular is taking a long hard look at commodity markets and whether large stock movements onto and off exchange might be deemed “insider trading”.

The LME is in the process of forming a committee to draw up a consultation document on “potential market conduct issues”.

Topping the to-do list is “transparency around bringing metal on and off warrant”.

For those disappointed that there were no real bomb-shells in the LME’s new reports, remember it’s still work in progress.

For now, though, we all already know a little bit more than we did before about how much metal is being stored “out there”.

(Editing by David Clarke)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments