Nickel price surge past $100,000 leaves big short with big trouble

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

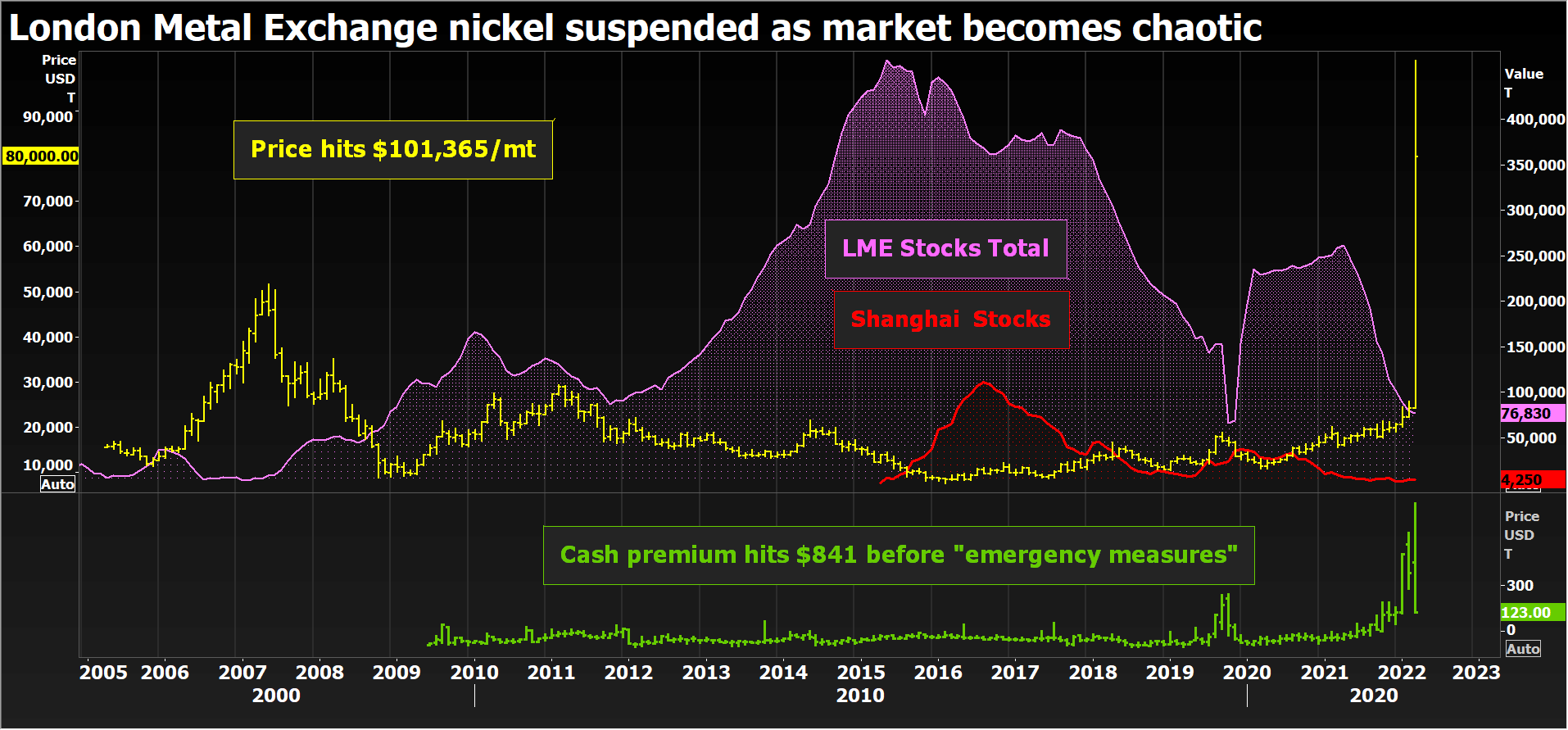

The London Metal Exchange (LME) has been forced to suspend all trading in its nickel contract after prices went into chaotic overdrive.

LME three-month nickel, the primary pricing reference for the global physical supply chain, hit $101,365 a tonne early on Tuesday, up from just $30,000 on Friday.

The contract was suspended at $80,000 as the exchange stepped in to halt trading at 0815 GMT. All Tuesday’s trades up until then will be cancelled until further notice, the LME said.

It’s not the first time the LME nickel contract has been suspended. The exchange had to halt trading briefly in 1988 after the cash price rose by 50% in the course of one five-minute ring-trading session.

Back then it was an absence of sellers that broke the nickel market. Today it’s one big seller.

The big short

As LME broker Marex Spectron said in a note to clients on Monday, “this is not a demand or fund-led rally now – this is margin and pain”.

The big short has been submerged in a perfect bull storm and is now struggling to meet ballooning margin calls.

The ferocity of the price action over the last 24 hours speaks to a forced liquidation of positions, a buy-back in a liquidity vacuum.

The exchange imposed emergency measures across all its base metals suite at the close of business Monday, providing for a daily lending cap and the potential for deferred short delivery.

China’s Tsingshan Holding Group bought large amounts of nickel to reduce its short bets and exposure to costly margin calls, turbocharging a rally fuelled by the conflict in Ukraine, three sources familiar with the matter said.

Tsingshan and the LME have declined to comment to Reuters.

The pain of holding that position in a rising market was increasingly clear from early January, when LME time-spreads started tightening.

The subsequent run on LME stocks turned into a full-blown squeeze last month.

The big short was already caught.

Tsingshan may be a huge nickel producer from its Indonesian operations but none of its metal is in the right form for LME delivery.

LME stocks have been falling consistently since the start of the year with open tonnage available for physical settlement totalling just 36,654 tonnes as of last Friday. Over half of that was in the hands of a single entity, according to the exchange’s dominant positions report.

With existing stocks so tightly held, any short position would have found it difficult to deliver physical metal leaving it vulnerable to any price rises.

And then Russia launched what it calls its “special operation” in Ukraine.

The perfect storm

Russia’s Norilsk Nickel produced 193,006 tonnes in 2021 or about 7% of global mine production estimated at 2.7 million tonnes.

The company is also, critically, a major supplier of refined nickel in a form that can be delivered against the LME’s contract.

Russian nickel is not sanctioned – yet – but accumulating restrictions on doing business with Russian entities have heightened fears about both the potential impact on the physical supply chain and the pool of LME-deliverable metal.

The price started rallying early Monday and picked up speed as it took out bands of call options sitting at strikes such as $29,000 and $30,000.

Sellers of those options were forced to hedge-buy against their exposure, pouring fuel on already raging fires.

By Monday’s official close, LME three-month nickel was valued at $48,078 per tonne, which will now be used to calculate margins going forward.

Collateral damage

There are some truly scary figures being thrown around the London market as to the scale of the margin pain and the short’s ability to pay.

There are also signs of a domino effect on short position holders in other LME contracts such as zinc, which has just somersaulted over $800 to $4,896 per tonne and back to $4,160 again.

The LME said it is monitoring all its other contracts, which continue to trade while it sorts out the mess that is the nickel market.

In the immediate term, this will be about avoiding or at least mitigating the impact of a potential default.

The LME is better cushioned against such an outcome than it was in the 1985 Tin Crisis, when there was no clearing house to protect brokers from the financial collapse of the government-backed International Tin Council.

Even so, the potential size of the potential losses is evidently sufficient to have forced the exchange to take extreme emergency action.

There is then the question as to how to repair what is in effect a broken nickel market.

Tsingshan is by no means the first to have found itself caught out by the narrow deliverability criteria of both the LME and the Shanghai Futures Exchange’s contracts.

Nickel supply is surging to meet electric vehicle battery demand but much of that growth is coming from Indonesia in the form of nickel pig iron, matte and, increasingly, battery precursors such as nickel sulphate. All of them can be hedged but none delivered against either exchange.

There may well then be scrutiny as to whether the LME itself needs repair in how it regulates price formation.

Regulators will be taking note, not least those in China, which could prove very uncomfortable for the exchange’s owner Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing.

(Editing by David Clarke)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments