LME faces fresh worries about Russian metal after UK sanctions

New UK sanctions on Russian metals have caused confusion among traders and raised fresh worries that the London Metal Exchange could be overwhelmed by a glut of unwanted Russian aluminum.

The sanctions, published by the British government Thursday with little fanfare, prohibit British individuals and entities from trading physical Russian metals, including aluminum, copper and nickel.

“These regulations could have far-reaching implications for any UK persons who are importing, acquiring, supplying or delivering a wide range of base and other metals from Russia,” said Tom Hine, partner at Kemp IT Law and former general counsel of the LME. “Anyone involved in activities in relation to Russian metals should consider their actions carefully and seek legal advice.”

While most large metal traders and banks are headquartered outside the UK, many have a significant presence in the country and have senior British staff, creating uncertainty about how broadly the sanctions would be followed. Some traders based outside Britain are unfazed by the sanctions, but others are responding by rushing to deliver any Russian metal they hold onto the LME, according to people familiar with the matter. That could show up in the exchange’s stock reports in the coming days, they said.

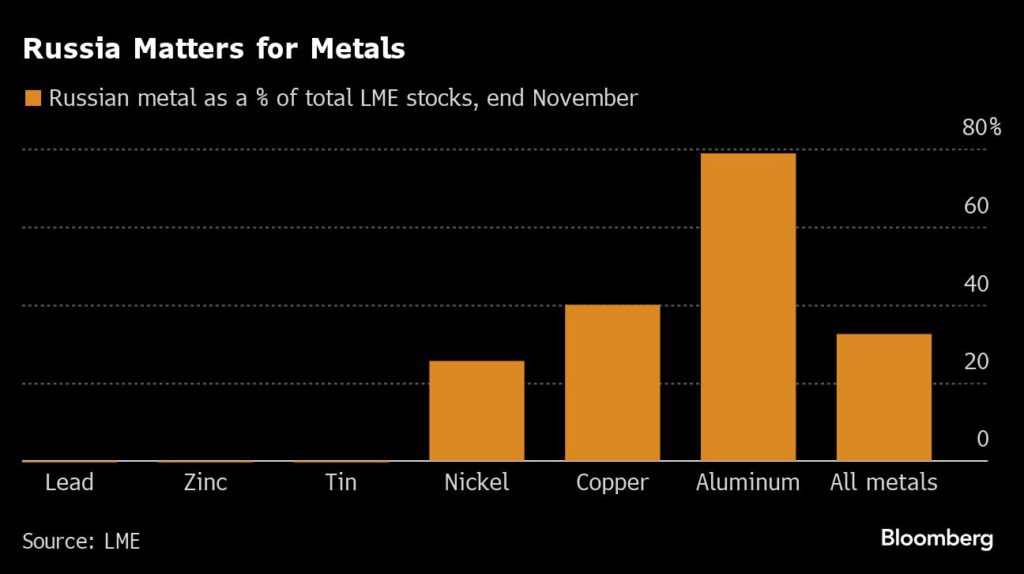

For the LME, the sanctions threaten to reopen a fractious debate over whether it should ban deliveries of Russian metal — something it considered last year, but ultimately decided against. Just under 80% of the aluminum on the LME was of Russian origin at the end of November, according to exchange data.

The LME and its members and clients were given an exemption to allow for the continued trading of derivatives backed by Russian metal on the exchange. But by restricting the ability of British entities to trade physical Russian metals, the sanctions will prevent them from taking physical delivery from the exchange of metal purchased after Dec. 15. That means what is already a small pool of buyers for Russian metal on the LME is dwindling further, making it more likely the bourse is stuck with a glut of unwanted metal.

“Our understanding is that UK entities and UK passport holders (at least) cannot take Russian metal out of LME warehouses (purchased from December 15th),” Max Layton, head of commodities research at Citigroup Inc., wrote in a note. “This may result in significant Russian inflows and spread weakness on the LME and eventually lead to the LME delisting Russian metal.”

An LME spokesperson declined to comment. The exchange had previously said it would be guided by the extent to which Russian metal continues to be consumed by physical market participants.

Active buyers

Until now, there have been no blanket western sanctions on metal trading, and some banks and traders had been active buyers. For example, Citi took delivery of about 75,000 metric tons of Russian aluminum in August. While Citi is a US bank, its membership of the LME is held via two UK entities — meaning it may no longer be able to carry out a similar trade in the future. A spokesperson for Citi declined to comment.

And Glencore Plc, which is listed in London but headquartered in Switzerland, is one of the biggest buyers of Russian metals through a long-term contract with United Co Rusal International PJSC. Glencore’s annual report states it adheres to US, European Union, United Nations and Swiss sanctions “throughout our business, whether we are legally required to do so or not,” but makes no mention of UK sanctions. A spokesperson declined to comment.

Any move by the US or EU to follow the UK’s sanctions on metals trading would likely force the LME’s hand. The British government hinted at the possibility of such coordinated action in the press release announcing the sanctions. The UK “plans to proceed with a prohibition on ancillary services relating to metals when this can be done in concert with international partners,” it said.

(By Jack Farchy, Archie Hunter and Mark Burton)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments