Juniors are the answer to gold industry challenges

Back in May, AngloGold Ashanti announced plans to sell its last remaining gold mine in South Africa, the Mponeng mine southwest of Johannesburg. Despite extremely rich 10 grams per tonne ore, “the challenges of making money at Mponeng are immense,” stated a media report, referring to the depth (it’s the world’s deepest mine) and high temperature working conditions. Whereas AngloGold Ashanti made about a billion dollars profit from its South African mines in 2011, in 2018 gross profits from its operations there barely register on a chart comparing its mines in other parts of Africa, the Americas or Australia.

At Ahead of the Herd we love gold (and promising junior gold companies) because gold holds its value through time. Owning bullion is a way to preserve wealth against paper currencies which are subject to inflationary pressures and over time, lose their value.

We also like gold because gold companies are finding less of it – this adds to gold’s allure, and will eventually be factored into its price. Not only is gold relatively rare compared to, say, iron or aluminum, it is also facing dwindling global reserves.

One of the most well-respected CEOs in the industry, Mark Bristow, who headed Randgold before it merged with Barrick, remarked on the tight gold supply in a recent interview with The Northern Miner. Asked to comment on how the gold industry could look in five to 10 years, Bristow had this to say:

The industry is in decline. We’ve got ourselves into a really tight spot because we haven’t invested in exploration and our future.

Now when you look at the average life of mine, it’s less than the time it takes to discover and develop a world-class asset. The supply side of our industry is very tight. The demand side … and I disagree with some of the talk presenters here today, in that gold is an inelastic industry just like everything else.

When we overdid the hedging and dumped twice as much gold into the market that we were actually producing, the gold price went to US$255 an ounce. We stopped doing it, and it started going up. The Chinese started buying gold, and it went even further.

Then all we did is we took lower and lower grades and produced more and more gold and we put a roof, a ceiling on the gold price and we’ve driven it down since then to a point now where we are staring at tightening in the market.

Bristow’s comments inevitably lead into a discussion over peak gold – the point at which gold production reaches a top, then begins falling, never to return to previous levels. Are we there yet, and if so, how long before we run out? What would peak gold mean for the gold market?

The answer is critical. If supplies can’t keep up with demand the price will only go higher. On the flip side, if there’s still plenty of gold to be found, theoretically the market could face a glut, pushing prices down.

There is in fact some evidence of a peak. A Thomson Reuters report said 2016 was the first year since 2008 that gold mine output actually fell – by 22 tonnes or 3%.

In June it was announced that South Africa – which led global gold production for a century and has mined half of the world’s bullion – lost its continental golden crown to Ghana. Lower-cost mines, friendlier mining policies and more projects under development catapulted the West African country to the top position, producing 4.8 million ounces in 2018 to South Africa’s 4.2Moz.

Predictions are that gold mining in South Africa could be done by 2050.

As for new gold mines, the bear market of 2012-16 meant most large gold companies slashed exploration budgets and juniors had an extremely tough time raising cash, to conduct drill programs that identify the next motherlode.

Yet the idea of peak gold has always been controversial and continues to be. If the amount of reachable, and economic gold resources is finite, presumably gold companies have a shelf life. It means gold mining is a sunset industry that will only see so many more bright orange spheres slipping over the horizon before the last ounce of gold is poured.

On the plus side, if gold is indeed becoming scarcer, prices have only one way to go and that’s up, so long as demand for the precious metal is constant, or growing.

As gold investors, we want to know the truth. In this article we are asking: Has the industry hit peak gold?

For the answer we turn to hard evidence, such as reports by McKinsey & Company, the World Gold Council, and S&P Global Intelligence. But first we need to know what happened in the gold market over the past few years to get us to the point where we even have to ask the question.

The making of peak gold

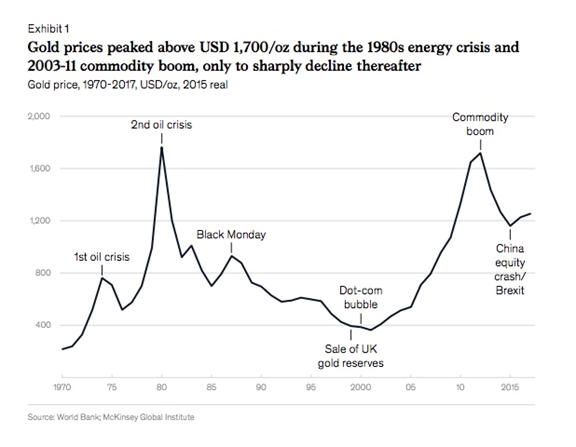

The burst of the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s ushered in the present gold market which rode the tailwind of a decade-long commodities boom. The mining supercycle started in 2001, when a one-ounce bar of gold could be purchased for $255, and peaked in 2011, when the gold price hit an all-time high of $1,907/oz.

As McKinsey’s chart below shows, gold’s dramatic rise has only been equaled once in the last 50 years, during the global recession of the early 1980s.

During the commodities boom, a continuously rising gold price had gold company CEOs uttering the mantra, production at any cost. Gold giants like Newmont, Barrick, Goldcorp and Newcrest tried to out-mine each other with the annual ounce count being the main driver of shareholder returns and CEO bonuses.

According to McKinsey’s research, between 2000 and 2012, annual capital expenditures by gold mining companies increased 10-fold, with the aggregate spend exceeding $125 billion. Two thirds of projects exceeded budgets by 60%, and half experienced delays of one to three years.

As new mines started up and existing ones were outfitted with the latest equipment, reserves started to thin out. At the time, it was thought the best way to replace reserves, along with brownfield exploration (tapping existing or historic mines), was through mergers and acquisitions (M&A); between 1998 and 2012, 42% of gold companies’ reserves growth came via M&A.

From 2000 to 2010, the industry saw over 1,000 acquisitions with a combined value of $121 billion, versus just $27 billion from 1990 to 2000. It was an all out acquisition spree, growth at any cost, growth just for growth sake. Quality of the acquisition sometimes seemed to be of secondary importance.

The problem was all these acquisitions were done at the height of the gold market when nobody, well almost nobody, thought the hype could end. Examples included Goldcorp buying Canplats at a 41% premium to its share price, and Newcrest offering Lihir Gold shareholders the same percentage premium for an $8.5 billion acquisition. Their sins would soon find them out.

By 2012 the gold party was over.

For gold companies, there needed to be a major shift in their thinking. How could they remain profitable, having gorged themselves for 10 years on acquisitions and capital expenditures, conducting their business like it was a Roman orgy, but now working with a gold price that had almost been cut in half? The answer was cost control.

From “production at all costs,” the new modus operandi was “aggressive cost-cutting, by all means”. Between 2012 and 2017 all-in sustaining costs (AISC) dropped by around 20%, through three main strategies, according to the McKinsey report: driving down costs, freezing capital expenditures and cutting debt.

A few notable facts regarding these three austerity measures:

- Cost-cutting programs were aided by lower crude oil prices (recall oil prices fell off a cliff in the fall of 2014) and lower exchange rates. The currencies in several key mining countries all depreciated against the US dollar between 2012 and 2017.

- Since 2012, all but one of the largest 20 gold companies has significantly reduced capex.

- Exploration budgets were cut drastically. Between 2012 and 2016, exploration spending more than halved, from $20.5 billion in 2012 to $8.7 billion in 2016. This included both greenfield and advanced-stage projects.

- The industry went to great lengths to repair over-leveraged balance sheets. Through a combination of asset impairments, asset sales and closures, industry debt was reduced by over $10 billion between 2013 and 2017.

With gold companies now leaner and meaner, and several having been obliterated during the vicious gold bear market of 2012-16, there are less firms to be acquired, and fewer ounces available for gold majors wanting to replace and expand their reserves.

Unless gold companies discover new deposits and build or buy new mines, they will eventually deplete themselves. As for getting more gold through acquisitions, while there has been a recent stir of gold M&A, consolidations have dropped considerably, to just $9 billion worth of deals in 2017, an 85% reduction from the gold M&A peak in 2011.

The case for peak gold

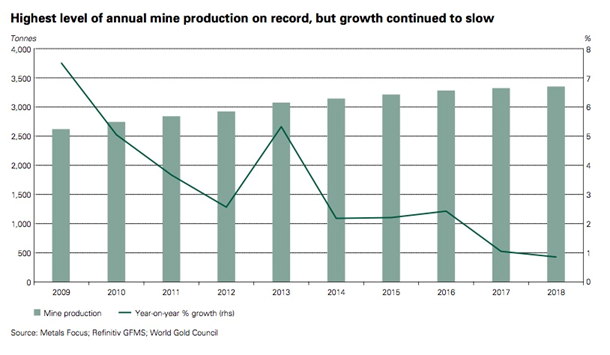

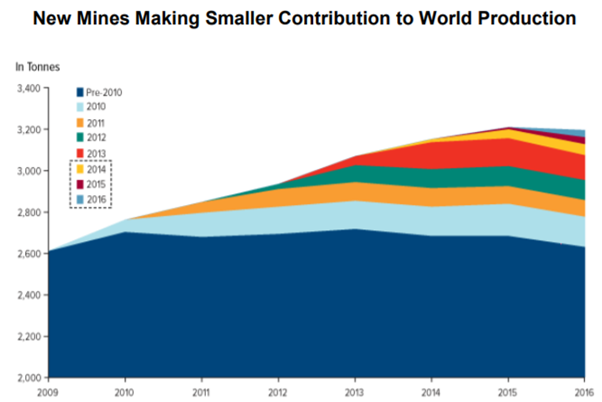

A compelling argument for peak gold is the fact that, while gold production has been increasing every year (except for 2016, noted above) – it’s been growing in smaller and smaller amounts. That is, while gold output in 2018 was higher than 2017, it was only 1% higher – 3,347 versus 3,318 tonnes, according to the World Gold Council. Gold production of 3,318t in 2017 was 1.3% more than 2016’s output of 3,274t. This phenomenon is shown graphically below.

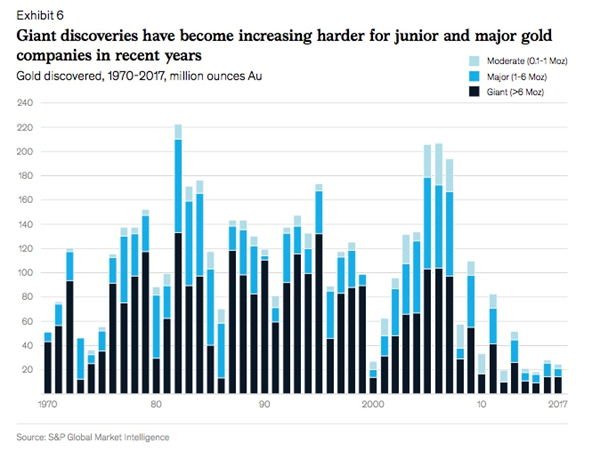

It’s not surprising that gold companies are finding it tougher to add to global reserves. The fact is, all of the easy, low-hanging fruit has been picked. Even with a six-fold increase in exploration spending between 2002 and 2012, there has been a significant dearth of new discoveries.

According to McKinsey, in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the gold industry found at least one +50 Moz gold deposit and at least ten +30Moz deposits. However, since 2000, no deposits of this size have been found, and very few 15Moz deposits.

Any new deposits will cost much more to discover. This is because they are in far-flung or dangerous locations, in orebodies that are technically very challenging, such as deep underground veins or refractory ore, or so far off the beaten path as to require the building of new infrastructure from scratch, at great expense.

The costs of mining this gold may simply be too high.

A few examples from the McKinsey report confirm the trend of diminished gold reserves:

- At the Witwatersrand Basin in South Africa, the largest gold field ever found, gold production has been cut 84%, from its 1,000-ton peak in the 1970s to just 157 tons in 2017.

- Australia’s Super Pit and the Carlin Trend in Nevada are both facing depleted reserves.

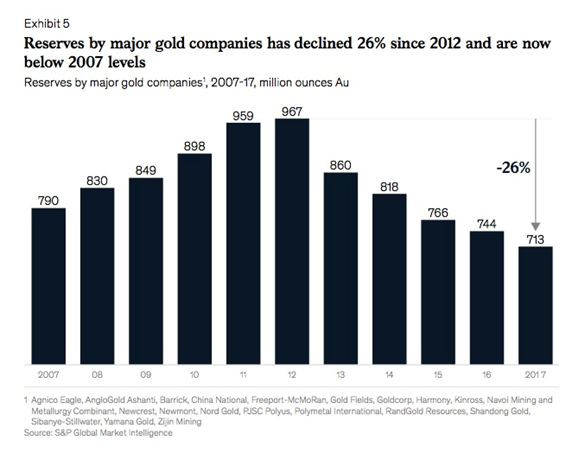

- The reserves of the major gold companies have shrunk 26%, from 967 Moz to 713 Moz, while the average life of mine is now 15 versus 19 years.

- Gold discoveries peaked in 2006 and since then there has been a decline in both the number of new discoveries and the amount of contained gold. This is despite the industry exceeding $50 billion in exploration expenditures, over the last 10 years, almost double the total spend of the preceding two decades. (ie. spending more, finding less)

Along with a lack of large discoveries, McKinsey & Co. offer three more reasons for why the gold reserve situation has worsened so much: funding for juniors has dried up, majors slashed exploration budgets and focused on brownfield development, and high-grading deposits has accelerated depletion.

It used to be that major gold companies had large exploration budgets with which to conduct programs to replace and expand their metal reserves. After the gold market crash in 2012, one of the first victims of austerity programs were majors’ exploration budgets. As an industry, annual budgets went from $10.5 billion in 2012 to just $3.2B in 2016. The following year saw a 20% increased to $4 billion, but still more than half of 2012 levels.

“The effect of this reduced spend and limited scope meant that mining companies were barely able to replace produced ounces while converting nearby resources to reserves,” the report states.

Moreover, the majors shifted their attention to brownfield projects from more risky green fields – leaving that to the gold juniors.

Discoveries < reserves depletion

The absence of major discoveries over the past several years, combined with reserve depletion, has put the gold industry in a real pickle. In the 1970s, every ounce of gold that got depleted was replaced by 2.6 ounces of new gold. Today, for every ounce of reserve depletion, only half an ounce is discovered.

Between 2013 and 2015, when gold was in a bear market, gold reserves fell by 17% to 1.3 billion ounces and gold resources dropped 14% to 2.5 billion ounces, according to a background report. Reserves in 2016 were 34% below their 2011 level, having declined for five years straight.

At that rate of depletion, and without meaningful discoveries, reserves and production will continue to drop. In fact, gold production is expected to peak in 2019, followed by a steady decline. Peak gold this year? Why not.

The low rate of discovery along with drastically less capital to put towards exploration, has left the industry with a weak pipeline of development projects. Of these future mines, many are lower grade than previous discoveries, in 2016 the average reserve grade for 266 producing primary gold mines (ie. no co/ by-product metals) was 1.47 grams per tonne, compared to 1.02 g/t for 310 undeveloped deposits.

Potentially less viable than high-grade operations, these future lower-grade mines will contribute less to global gold production.

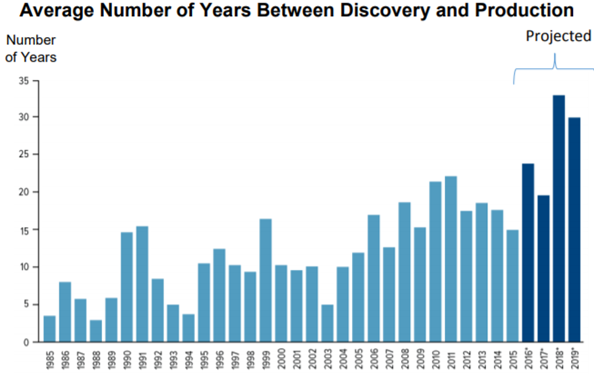

And there’s another problem: It is taking longer, much longer, to commission greenfield mines. While it used to take 12 years to bring a new discovery to production a decade ago, today it will be 20 years. Some mines in sensitive jurisdictions, like the US and Canada, requiring copious environmental studies and special interest group sign-offs, could take up to 30 years!

High-grading —-> reserve destruction

Another key point to realize about peak gold – and this is the most important takeaway from this article – is the practice of high-grading. High-grading is what often occurs when a gold-mining company’s costs are higher than it would like them to be, cutting into profitability and market capitalization.

It’s a little more complicated but keeping it simple – a typical mining operation takes different grades of ore from different areas of the mine and blends it. The idea is to provide a steady, grade-controlled ore feed to the mill.

With high-grading, instead of mining a deposit as it should be, economically, by extracting, blending both low-grade and high-grade ore at a given strip ratio of waste rock to ore – the company “high-grades” the orebody by taking only the best ore, leaving the rest in the ground.

The effect is to immediately boost the company’s profits, since it is spending less to move material than was planned for in technical reports (PEA, prefeasibility study, feasibility study), and the higher-grade ore fetches a higher price per tonne. A company employing this mining method will fat margins.

The problem is that glossing over the lower-grade material effectively removes it from the company’s reserves, until the gold price rises and it can be economically extracted again. There may also be technical challenges in getting to that lower-grade ore, making it too costly to extract even at a higher price.

The implication of high grading is a dramatic improvement in a company’s margins, but at a huge loss of ounces to its reserve base, as well as lowering the deposit’s average grade, since all the best material has been removed.

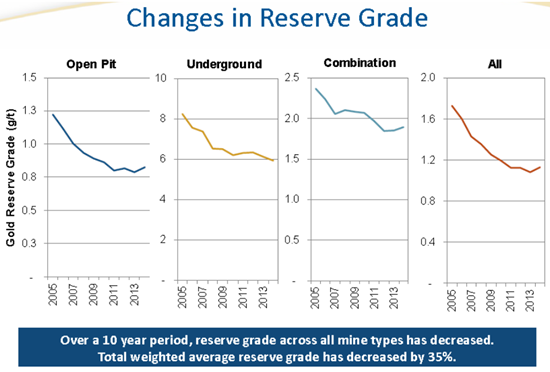

The evidence of high grading, the smoking gun, is revealed in the changes to gold reserve grades over the years. The chart below shows that for both open pit and underground gold mines, and a combination of the two, reserve grades over a 10-year period fell 35%.

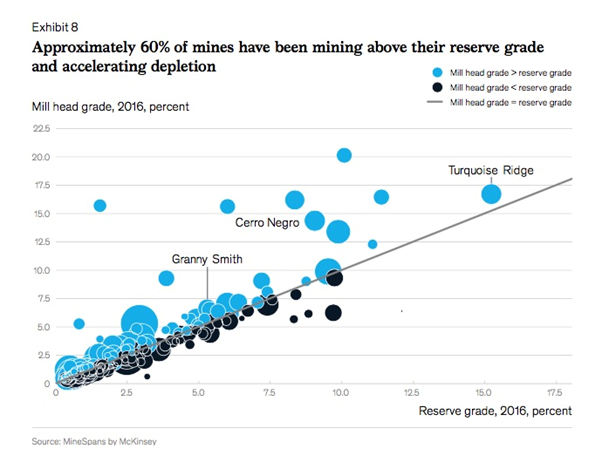

According to McKinsey, in 2016, about 60% of gold operations were mining with mill grades above the mine’s reserve grade – in other words, they were high grading. Large mines where this was occurring included Goldfields’ Granny Smith mine in Australia, Goldcorp’s Cerro Negro, Argentina and Barrick’s Turquoise Ridge operation in Nevada.

Notice the blue circles that represent mill head grades at gold mines in 2016 that were higher than reserve grades. The black circles are mines where mill head grades were less than the reserve grades. The head grade is the average gold grade that will be fed into the mill. Two takeaways from the graph – first, there were many more blue circles than black, showing more mines high grading than not. Second, some mines were sending ore through the mill at grades way richer than reserves – up to 20 grams per tonne higher.

There is no reason to think the practice of major gold mining companies high grading their reserves has stopped. Gold mining is a low margin business, in fact companies rarely make money at it. The one way to ensure profitability by maximizing your returns and minimizing your costs of production, is high grading.

We know from a combination of McKinsey’s and Dundee Capital Markets’ data, that it’s been going on since at least 2005.

But there’s more to it than just a gold company fattening up its margins and robbing Peter, representing the long-term life of mine, to pay Paul, the next couple of business quarters. High grading provides the fuel for mergers and acquisitions. The way it works is this: Major gold companies are running out of ore, as they churn through reserves that were discovered 15 – 20 years ago. It costs too much, takes too long, and is too risky exploring greenfield projects, so they let juniors do that. They could expand their mines, or explore in and around others they acquire, but that too requires heavy expenditures.

Instead a gold major high graded its reserves, which boosts its earnings, and fills its coffers in order to be able to afford an acquisition. If the deal is approved, the company not only gets new reserves – solving the problem of depletion – it also gains the opportunity to high grade the new reserves, at the cost of many hundreds of thousands, or millions, of ounces, plus lower grades.

Also, lumping the new reserves into their existing ones disguises the fact they’ve been high grading, which wouldn’t go over well with shareholders.

Gold miners use shareholder money to high-grade reserves to achieve maximum revenues from gold sales. Costs remain low because much less earth is moved to get the best ore. Its treasury bulked up by high grading, the company is then in a position to buy a company and its reserves, thereby replacing those lost to high grading. Rinse and repeat.

High grading in a falling gold-price environment has reportedly diminished the lifespan of existing mines. According to Scotiabank, the average mine life of the miners it covers has fallen from 19 years to 12 – the shortest in 30 years.

Finally, sourcing ounces through acquisitions (after high grading) is neither sustainable nor cost-effective. Between 2006 and 2015, the average cost of acquiring reserves was $241 per ounce – six times the cost of adding reserves through exploration, states the background report.

High grading their reserves is terrible for the industry, because short term profits are made while inflicting long-term pain, in that millions of ounces are left unrecovered, and likely never will be, unless the gold price rises enough for those lower-grade reserves to be economically mined.

In sum, the combination of high grading, which lowers both reserves and grades,

a drastic reduction in new discoveries due to a lack of exploration spending, and decreased mine lives, means the industry will be extremely challenged to maintain current production levels. According to the background report, by 2020 global mine production is expected to drop 3% to 95 million ounces and keep falling after that – in other words – peak gold. The report estimates that by 2025 production will be one-third lower than 2020’s output.

Junior pain

As mentioned, within the past several years, large gold companies have shifted from greenfield (early stage) to brownfield (historic producer) exploration. Whereas in the 1980s, junior gold companies discovered 10-30% of new mines, after 2000 they have accounted for up to 75%, according to the McKinsey report.

Passing on the responsibility for greenfield exploration to the juniors – which in our universe of companies consists of firms under a $50 million market cap – would have been fine if the money pipeline to these companies kept flowing.

A junior resource company’s place in the food chain is to acquire projects, make discoveries and hopefully advance them to the point when a larger mining company takes it over. Discoveries won’t be made if juniors aren’t out in the bush looking at rocks.

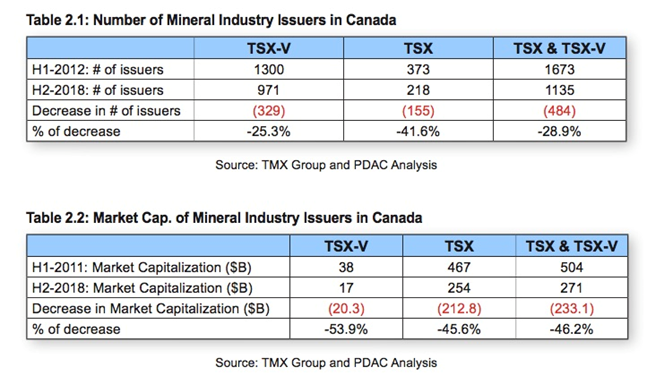

But junior mining financing has pretty much dried up. Between 2017 and 2018, bought-deal financings, whereby investment banks buy chunks of shares from juniors – have slumped 40%.

A 2019 report by deal tracker Oreninc and the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) paints a glum picture of our junior resource market, albeit with a few bright spots.

First of all, we note that the number of mining industry issuers has dropped considerably over the past few years on the materials-centric Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and its sister TSX Venture Exchange. Whereas in the first half of 2012, there were 1,300 companies listed, by H2 2018 they had dropped to 971 – a decrease of 329 juniors. As of June, there are 948 mining issuers on the TSXV, out of a total 1,700 companies on the exchange – showing a 79% concentration in mining.

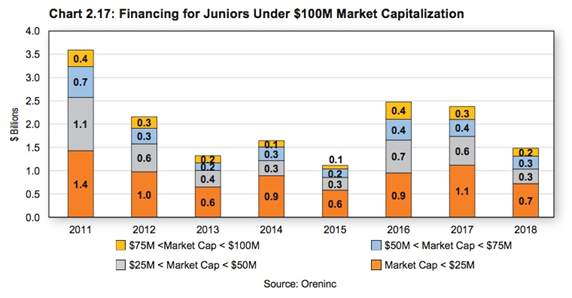

Honing in on the report’s figures for mining companies under $100 million market cap, Oreninc tells us that funding has declined 38%, from $2.4 billion in 2017 to $1.5 billion in 2018. This compares to a 30% drop for a much larger data set of juniors under a $1.5 billion market capitalization, showing that smaller companies suffered most in 2018.

Companies with market caps from $0 to $25 million, and $25-50 million, lost 40% and 60% of funding, respectively, compared to 2017.

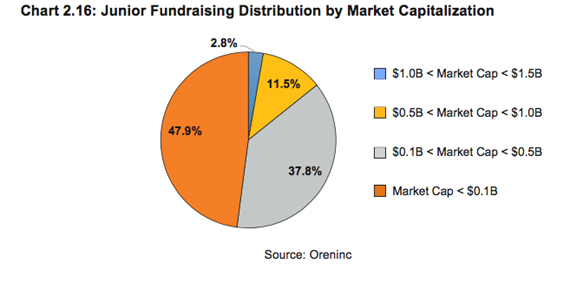

However, Oreninc also notes that, between 2011 and 2018, nearly half (47.9%) of all junior funds raised were by companies under $100 million market cap, whereas companies above $500 million market value raised under 15% of the funds.

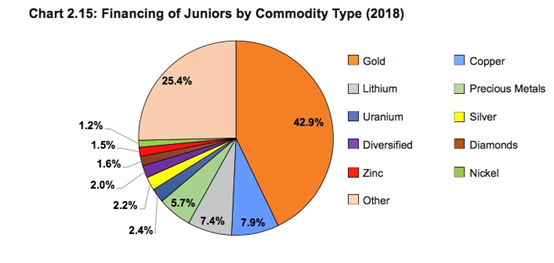

It was also noted that of the various commodity types, gold was by far the leader, with 42% of funds raised in 2018, compared to 2.2% for silver and 7.9% for copper.

Getting loans from banks has also become more difficult, considering the long lead time from discovery to production, and to cash flow. McKinsey notes the largest funding packages have been offered to late-stage projects or brownfield expansions.

1,000-tonne annual deficit

Returning to the question, ‘Have we hit peak gold?’ means checking on some key statistics from the World Gold Council (WGC).

It’s a tricky question though. Conventional wisdom holds that peak gold is the point when the amount of gold supply hits a ceiling, then stops increasing. By this definition, as shown by an earlier graph, gold has been increasing, year by year, although by smaller and smaller amounts – supporting the idea of the gold supply slowly building to a top.

But if we define peak gold as the point when mined supply no longer meets gold demand, the gold market peaked a long time ago. Allow me to explain.

Last year (2018) gold demand reached 4,345.1 tonnes.

WGC reports that 2018 was a record year for mined gold production – 3,347t.

Gold jewelry recycling was 1,173t, bringing total gold supply last year to 4,520t.

If we stop there, we show a slight gold supply surplus of 175 tonnes. Peak gold debunked!

Not so fast, let’s think about those numbers for a minute. In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we, at Ahead of the Herd don’t, and won’t, count jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t! When we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, we get an entirely different result. ie. 4,345 tonnes of demand minus 3,347 tonnes of production leaves a deficit of 998 tonnes.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, even hitting record gold production in 2018, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,173 tonnes of gold jewelry could gold demand be satisfied.

Now the question becomes, how do we, or can we close that 1,000-tonne (for round numbers) gap?

One way is to wait for a higher gold price, so that gold companies can go in and mine all the lower grade gold that was left over from high grading.

How about new supply coming online? Well, we have a good idea of what that looks like, thanks to a recent report from S&P Global Intelligence. S&P is forecasting that over the next decade, major discoveries will increase to about 363 million ounces. That’s 11,343 tons, or 1,134t per year – enough to meet our 1,000-tonne deficit. But here’s the kicker: According to S&P, previous research found it took 20 years to advance a greenfield gold project to production. Say the first 1,134 tons of gold, of S&P’s projected 11,343t, is discovered this year. It will be 2039, at the earliest, before any new gold is poured, which doesn’t help with our current supply deficit at all, does it?

We’re also being rather optimistic that the entire 1,134 tonnes found in 2019, and every year for 10 years of S&P’s 363 Moz of new gold, is in the right ballpark.

Mine plans change, there may be strikes, or delays, plus the entire gold reserves are never completely mined out. Remember average mine life has dropped to about 12 years, so the operator has less time to mine and process all the gold promised in technical reports like the PEA. Not only that, the gulf between discovery and production has widened. It is estimated that, due to so many hurdles, only one-third of a company’s gold resources will ever reach the mill! Recall also, that it now takes 20, and in the future, possibly up to 30 years for a new mine to reach production. A lot can happen in 20 to 30 years.

Ah, you say, what about gold that was discovered 15, 20 years ago that is about to go into production this year, next year, and so on? S&P Intelligence has an answer for that question, too. Spoiler alert: it doesn’t correct our deficit, either. The research firm predicts a 2.3 million ounce (65-tonne) increase in 2019, with over half of that additional output coming from recently commissioned mines. That’s great, but it still doesn’t come anywhere close to meeting last year’s gold mining deficit of 998t, without having to recycle jewelry.

Rising demand

We’re also not taking into account the fact that gold demand might go up, and it probably will. That would mean having to find even more gold per year, maybe it’s more like 1,500 tonnes, or 2,000t, just to meet the demand. You can see where we’re going with this…

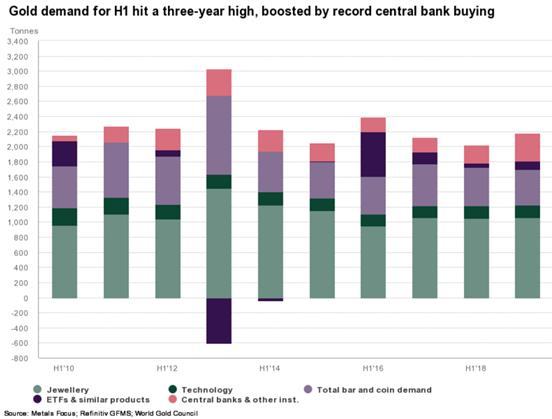

The World Gold Council’s latest report shows gold hitting a three-year high in the first half, lifted by record central bank buying, as central bankers re-position their holdings in reaction to a more dovish global monetary environment. They see Treasury yields slumping and real yields low or negative, so they are backing up the truck for gold.

The precious metal used mostly for jewelry and investment purposes has booked impressive gains year to date.

We know that President Donald Trump wants a massively lower dollar and will do anything to get it, including using the trade war with China as a means of getting the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. Read more at Trump’s perfect gold storm

Trump thinks a low dollar is the way to bring jobs back to the US after so many were exported abroad to take advantage of lower labor costs. He wants to rebuild the US manufacturing sector, primarily through cheaper exports. He’s particularly targeted China for competitively devaluing its currency to dump cheap exports into the US, such as steel and aluminum. All Chinese imports into the US are now subject to tariffs of between 10 and 25%.

Beyond the trade dispute, there are other reasons for owning gold that we outlined in a previous article. They include safe-haven demand driven by such dangerous conflicts as the war in Yemen, the frequent tensions between the US and Chinese navies in the South China Sea, and the close call with Iran recently over a drone strike.

On Monday the Trump administration froze all of Venezuela’s assets, putting the South American failed state in the same company as Cuba, North Korea, Syria and Iran. NBC News reports the ban blocks US companies and individuals from doing business with the Maduro regime and its top supporters.

There is also a brewing confrontation between South Korea and Japan over a set of disputed islands in the Sea of Japan. The South Korean Military wants to conduct defense drills at the Takeshima islands which are claimed by Japan but controlled by South Korea. According to Japan Times, the conflict is the latest in a series between the two former WWII adversaries, that stem from court rulings last year ordering Japanese firms to pay compensation to South Koreans, forced to work for them during the war.

Finally, something we predicted several months ago looks more likely – an arms buildup between the US and Russia. A week ago Friday the US formally withdrew from the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Agreement (INF), which restricted missile launches from the two Cold War enemies. Without a new agreement in place, there is nothing stopping Russia from developing new missiles pointing at Europe, and the US responding in kind, or vice versa.

Resource nationalism

Consider too that there will always be resource nationalism, no-go zones where gold mining is either too dangerous for gold companies to paint a target on their backs, or too risky to gamble shareholders’ equity.

While resource nationalism is among the worst things a mining company can encounter when investing in a foreign country (just ask Crystallex which fought Venezuela for years over a 2008 decision to expropriate its Las Cristinas gold project, finally winning a $1 billion settlement), it can also have an impact on metals fundamentals. If enough supply is taken out of the market due to government-imposed restrictions, prices of those metals will rise.

Retirement tsunami

Finally, looming labor shortages threaten to derail the best-laid plans to boost gold output, the next decade and beyond. A combination of mass retirements and increasing natural resource demand from emerging economies has created a crisis in the resource extraction sector.

The Mining Industry Human Resources Council (MIHRC) has said that about 40% of the resource extraction industry’s workforce is at least 50 years old and one third of them are expected to retire by 2022.

The organization also forecasts that the Canadian mining industry will face a shortage of 140,000 workers by 2021 – this number of workers being needed just to maintain current levels of production.

The skills shortages are global, they are happening in South Africa, Australia, Canada and South America. Costs are increasing, projects are being deferred or even canceled due to the inability to staff operations – tighter labor markets also provide unions with greater bargaining powers when dealing with companies over wage settlements and other disputes.

This retirement tsunami has taken a long time to build, but it won’t be long before it reaches landfall. Just when we need the mining industry most

we are starting to suffer a massive loss of accumulated wisdom, knowledge and field experience. This means future mineral output will be constrained and that has bullish implications for prices.

Conclusion

Peak gold is a divisive topic. Mining and exploration companies hate the idea, since it implies a sunset industry. Investors love it, because it indicates a long-term, bullish trend that would keep upward pressure on prices, assuming demand is static or increases.

As for whether we have reached peak gold, the interesting number is the record amount of gold mined in 2018 – 3,347 tonnes. Is this the most gold the industry will ever produce? We’ll find out when the WGC’s 2019 full-year report comes out. To avoid the peak gold cat-calls, production will have to hit another record.

But here’s the thing. You can’t just look at the amount of gold output one year versus the previous year, and if there’s an increase, conclude that peak gold is wrong. It’s a valid argument to assert that gold reached a peak when mined supply failed to keep up with demand; in 2018 the industry mined a record amount of gold. Yet that record amount fell 1,000t short of fulfilling new demand for gold. The gold mining industry for all the reasons mentioned in this article, cannot now, and will not, in the future, be able to meet ever increasing demand for gold.

The gold market currently relies on around 1,000 tonnes of recycled jewelry to meet orders for gold.

What we have here is an unsustainable gold industry, driven by greed and funded by shareholders who are unaware of what’s going on behind the scenes. As the industry continues to high grade and consolidate through M&A, eventually there will be so few companies left to acquire, in order to keep production and profits rolling in, that gold companies will finally have to stand on their own. It’s at that point that the real numbers will start to show, that all they have left are their lower grade gold reserves, and not as much as people think.

Sure, we can keep discovering and mining new gold fields, and we hope that continues for a long time. But recognize that, like all other metals, gold reserves and production estimates are always optimistic; they almost never match the original figures.

Only a third of a mine’s reserves make it to the mill and the average life of mine (LOM) has dropped from 19 to 12 years. The rapidly depleting reserves and grades, exacerbated by high grading, will accelerate a fall in gold production – a change of direction from many years of annual increases – perhaps as early as this year, certainly something that is going to happen very near term.

Throw in safe-haven demand from a more volatile, dangerous world, the spectre of future financial crises, currency wars and the already-happening de-dollarization, plus resource nationalism and the loss of mining expertise to retirements.

Adding it all up points to a looming scarcity of gold, a trend that can only be managed, not reversed. We’re never going to meet today’s 1,000-tonne shortfall, never mind future increases in demand; peak gold is not a theory it’s a fact, and that can mean only one thing: higher prices.

Gold is, in this author’s opinion, an extremely undervalued financial instrument.

But historically, and perhaps especially so today for all the reasons listed above, the greatest leverage to rising precious metals prices has been owning the shares of junior resource companies focused on acquiring, discovering and developing precious metals deposits.

Importantly, juniors are a cost-effective answer to the problem of gold reserves depletion. Because gold reserves are being used up faster than they are being replenished, it behooves the industry to come up with a strategy for reversing this trend – one that doesn’t involve high-grading and M&A. Rather than adding to the pot of global reserves, the latter “pours reserves from one pot to another,” asserts Stephen Letwin, the President and CEO of IAMGOLD Corp. Letwin’s excellent report ‘Growth in a Time of Reckoning’ is required reading for anyone interested in peak gold and how to replace gold sustainably – something we are not currently doing and desperately need to change.

In his report, Letwin states that while there are multiple ways the industry can boost its reserves, exploration is the only way to create long-term value for the industry. The cost of the status quo is to rapidly deplete global gold reserves, leaving millions of tonnes of low-grade ore that cannot be mined until much higher prices. Here’s Letwin:

The industry is ready to resume growth, but let’s do it the right way. Strategies that continue to see global reserve increases replacing only half of production will not create long-term value for the gold industry. Growth strategies in the industry should be those that expand resources at existing mines, identify near mine deposits that can leverage existing infrastructures and lead to new greenfield discoveries. Only through strategies that increase the global pot of mineable reserves can we reverse the trend in reserve replacement. Acquisitions play a role, but unless for the purpose of developing an asset that otherwise might not happen, they accomplish little but a change in ownership. Some believe the trend can’t be reversed; let’s prove them wrong.

Do you want to own the cheapest gold and silver you can find to reap the maximum coming rewards? If you do, buy it while it’s still in the ground.

The fact is junior resource companies – the owners of the world’s future precious metal mines – are on sale. If you like their management team, their projects and their plans for 2019, perhaps now is the time to be acquiring a position.

Why? Well besides the fact that I believe that precious-metals-focused junior resource companies offer the greatest leverage to increased demand and rising prices for precious metals, there’s obviously going to be a very real and increasing trend for Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A). Juniors, not majors, own the world’s future mines and juniors are the ones most adept at finding these mines. They already own, and endeavor to find more of, what the world’s larger mining companies need, to replace reserves and grow their asset bases.

Gold’s bull market is not over and here at Ahead of the Herd our edge is two-fold. First, it’s being right about the future for precious metals. Second, it’s having an excellent selection of well-managed juniors with plenty of metal in the ground to gain the desired leverage to rising gold and silver prices.

Precious metals-focused junior companies are again going to have their turn under the investment spotlight and should be on every investor’s radar screen.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments