Is platinum’s explosive rally the start of a bull run?

Platinum has broken out of more than a decade of price weakness to reach its highest since 2014, as investors anticipate that rising demand, including from the budding hydrogen industry, will surpass supply and support a lasting rally.

Years of oversupply and weak demand for platinum, used by auto makers, industry and jewellers, dragged prices from $2,290 an ounce in 2008 to $558 last year.

But prices have rebounded as the global economy started to recover from the covid-19 pandemic and gained more than 20% this month to above $1,300.

“We now see signs of speculative excess”

Carsten Fritsch, Commerzbank

“I can see further price increases coming,” said Bank of America analyst Michael Widmer, saying the market would see large deficits from 2023 and platinum could mimic palladium, which surged because of consistent undersupply.

“Look at palladium – you had a 10-year bear market (from 2001) – and then prices moved up by 1500%.”

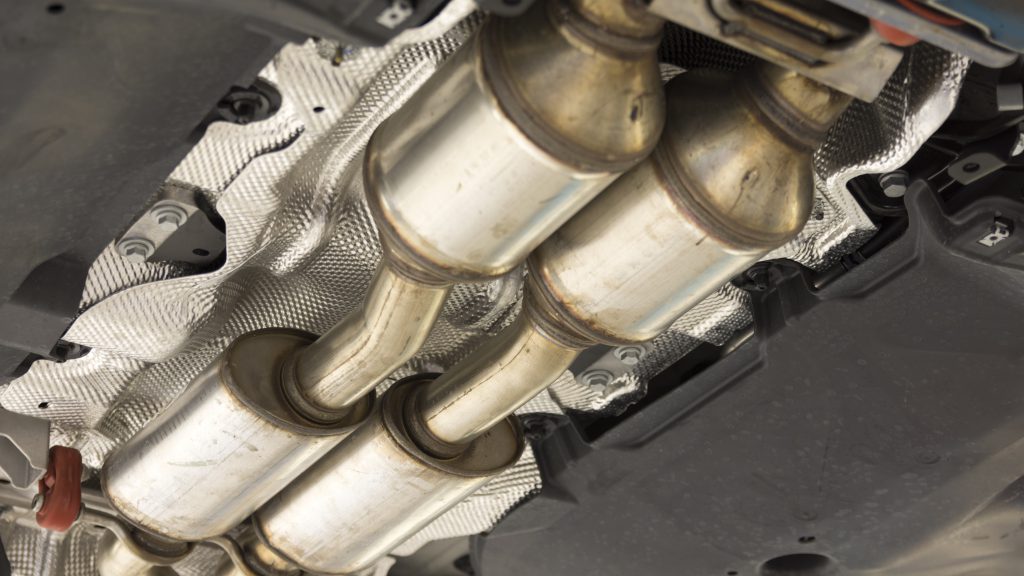

Auto makers account for around 40% of annual platinum demand of around 8 million ounces, embedding it in exhaust pipes to neutralise harmful emissions.

Manufactures have for years preferred palladium and rhodium for the task, but high prices of those two metals have begun to push many back to platinum, Johnson Matthey said in a report.

Analysts at Citi expect auto makers to use around 800,000 ounces less palladium and 800,000 ounces more platinum by the end of 2022, reducing total palladium demand by 8% and increasing total platinum demand by 10%.

Tighter Chinese emissions rules and higher sales will meanwhile raise the use of platinum in heavy duty vehicles by 50% this year alone, Johnson Matthey said.

Over the longer term, a shift from gasoline and diesel will reduce demand for platinum to clean exhaust fumes.

But an alternative to fossil fuels is hydrogen, and platinum is used in electrolysers to make hydrogen and fuel cells using it to power cars, trains and ships.

Demand for platinum in fuel cell-powered vehicles could rise to 2-4 million ounces a year by 2030, Bank of America’s Widmer said.

Investors are taking note, ramping up their bets on higher prices in U.S. futures markets and stockpiling bars in exchange traded funds.

But with big deficits still a couple of years away they may be unable to maintain recent momentum.

“We now see signs of speculative excess,” said Carsten Fritsch at Commerzbank, suggesting prices may need to fall in the near term.

(By Peter Hobson; Editing by Pratima Desai and Barbara Lewis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments