Is gold still a worthy investment?

After a hot start to the year, gold’s performance has somewhat subdued in recent months despite the usual supporting factors staying intact, namely high inflation and a bear stock market.

Year-to-date, spot gold has only managed a moderate gain of 6%, which is quite a downturn compared to the double-digit returns and near record highs we saw back in May. It’s also pretty underwhelming compared to the supposedly weak stock market. The S&P 500, for example, has a YTD gain of 16.1%. Nasdaq was even better at 27%.

Clearly, something must’ve happened along the way that made gold not as lucrative as before. And it now begs the question as to whether bullion remains a worthy investment, or has its popularity somewhat waned.

Frankly, the answer rests on the kind of portfolio we’re talking about, as well as the timeframe of the investment. As Investopedia points out in this article, gold, like stocks and bonds, isn’t a foolproof asset, and so its price fluctuates depending on a multitude of factors in the global economy.

Gold’s role in portfolio

With gold, it really comes down to understanding what role it plays in a portfolio.

First of all, gold is considered a safe investment, meaning it’s supposed to act as a safe haven when markets are in decline, because the price of gold typically doesn’t move with market prices.

As a result, gold also can be considered a risky investment, as history has shown that the price of gold does not always go up, particularly when markets are soaring. Investors typically turn to gold when there is fear in the market and they expect prices of stocks to go down. And so, in a sense, gold can also be volatile.

Secondly, gold is not an income-generating asset. Unlike stocks and bonds, its return is based entirely on price appreciation. Moreover, an investment in gold carries unique costs. As it is a physical asset, gold would require storage and insurance costs.

“Taking into consideration these factors, gold works best as part of a diversified portfolio, particularly when it is acting as a hedge against a falling stock market,” Investopedia writes.

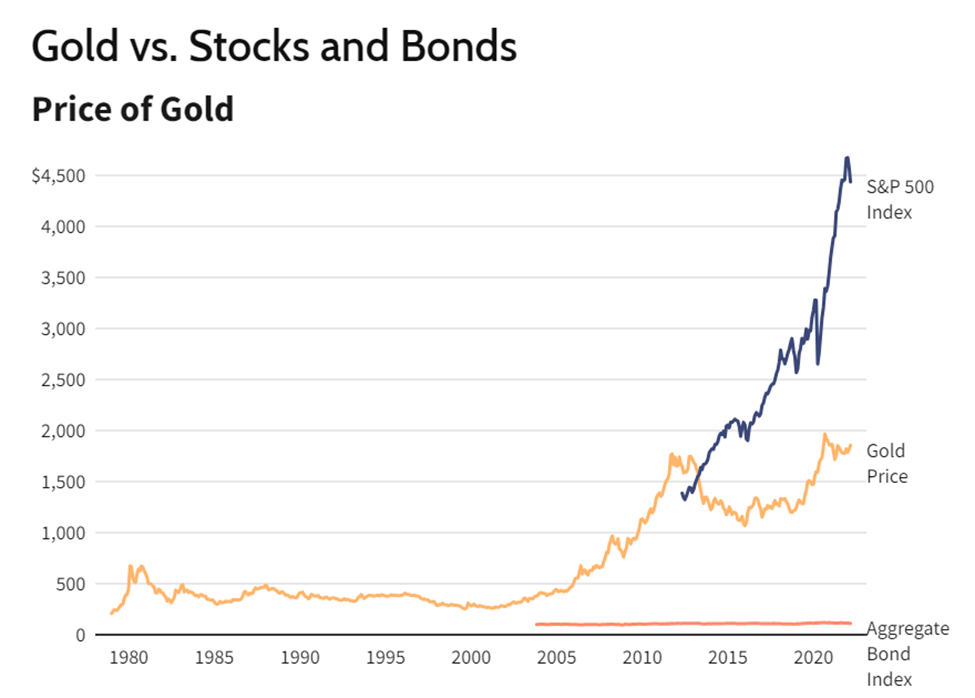

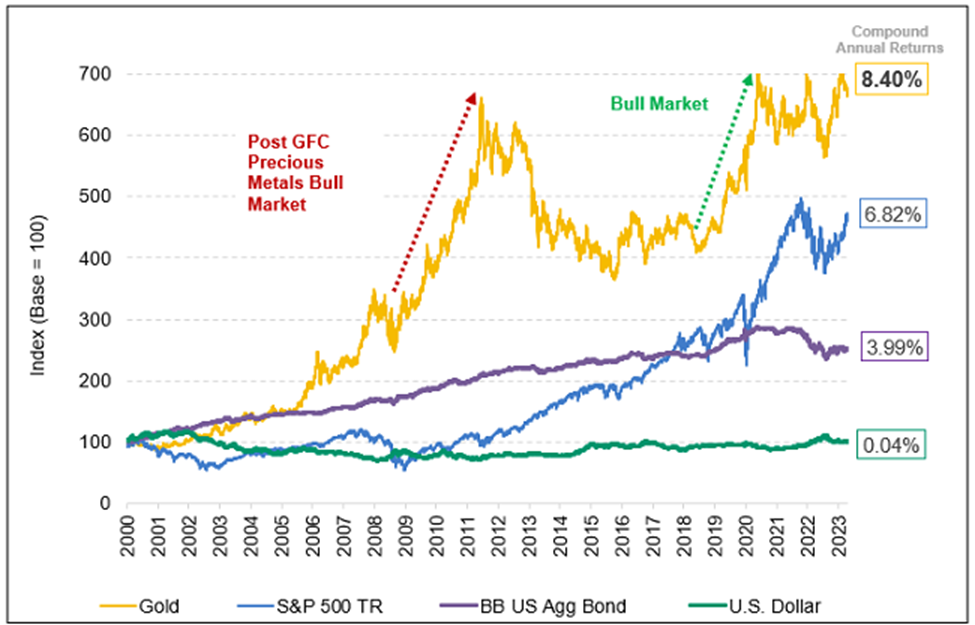

The time horizon is also important, because, as the Investopedia article points out, over certain 30-year periods, stocks have outperformed gold and bonds, but over some 15-year periods, gold has outperformed stocks and bonds.

For example, from 1990 to 2020, the price of gold increased by around 360%, but that’s easily trumped by the 991% gain recorded by the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) during the same period. However, if we look now at the 15-year period from 2005 to 2020, the price of gold increased by 330%, roughly the same as the 30 years considered above. Over that time, the DJIA increased by only 153%. Then, if we only consider the years 2021 and 2022, gold has outperformed stocks as geopolitical uncertainty and inflation increased worldwide.

So, over the longer term, stocks seem to outperform gold by about 3-to-1, but over shorter time horizons, gold may win out. Indeed, if we go way back to the 1920s through today, stock returns blow gold away.

As for bonds, the average annual rate of return on investment-grade corporate bonds going back to the 1920s through 2020 is around 5%. This indicates that over the past 30 years, corporate bonds have returned around 330%, similar to gold. Over a 15-year period, the return on bonds has been lower than that of both stocks and gold, as illustrated in the chart above.

Historically, as Investopedia points out, gold returns vary depending on the time period under consideration. From January 1971 (when the dollar became unlinked to gold) to December 2019, gold had average annual returns of 10.6%. Over the same period, global stocks returned 11.3%.

But if we’re just talking about the 21st Century, then the yellow metal has performed exceptionally against its usual comparables, with two noticeable bull markets that started in the latter years of the 2000s and 2010s (see below).

Reasons for gold’s underperformance

Nevertheless, we cannot deny that gold has had a relatively weak performance dating back to last year. Richard Bowman, equity analyst and writer at Simply Wall St, highlighted two main reasons for this:

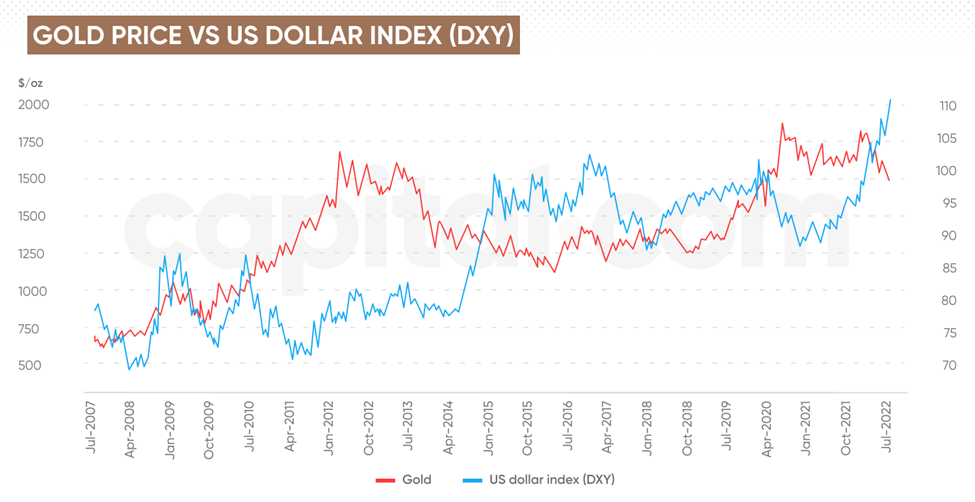

Firstly, gold is priced in US dollars, so when the dollar is strong – as it has been most of 2022 – gold appears relatively weak. This is also why the greenback is often considered an alternative safe haven to gold.

Secondly, higher interest rates have made leveraged positions more expensive to hold and have magnified losses as prices have fallen. Gold rallied sharply in 2020 when central banks began quantitative easing programs (which increased the money supply) and again in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. And then, inflation began to spike.

According to Bowman: “It’s likely that a lot of this buying was made with leverage when rates were very low. As gold prices fell, those positions fell into a loss (which was magnified by the leverage), while the cost of owning the positions increased due to higher rates.”

Indeed, we have witnessed global central banks hiking interest rates at their fastest pace in modern history to stave off inflation. In the US, the monetary tightening has boosted the dollar, which in turn suppressed bullion’s value as a popular inflation hedge.

“The problem at the moment is that inflation has gotten so out of control and central banks are being forced to hike rates like we’ve not seen in a lifetime,” Brian Gould, head of dealing, Australia at Capital.com, wrote in this Bloomberg sponsored article. “If you look at gold against the US dollar, we reached new all-time highs in 2018, and the market has fallen back since. It looks quite dramatic, and this year, gold is down against the dollar.

“So, there’s an argument there that, yes, it can be held as an inflation hedge—just not against the dollar. For all intents and purposes, gold trades more like a risk asset a lot of the time,” Gould stressed.

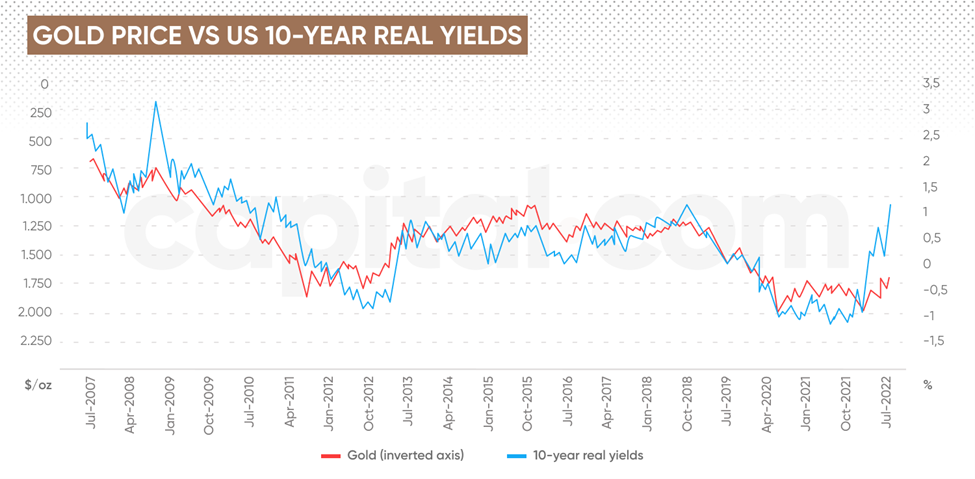

Gold prices are linked to US Treasury real yields, or net returns of expected inflation, according to Piero Cingari, Forex and Commodities Analyst at Capital.com.

“When US real yields increase, gold’s value decreases and vice versa, because a higher real expected return on a safe asset like US Treasury bonds discourages investment demand in non-yielding assets, such as gold,” Cingari says.

In other words, when investors assume that the Fed will continue raising interest rates aggressively and will be successful in lowering inflation, that’s not a good environment for gold, as Treasuries offer relatively more attractive returns.

“However, when the market believes that inflation cannot be significantly reduced even when interest rates rise—as it may be dependent on supply-side factors such as an energy crisis over which central banks have little or no control—gold returns to the forefront of investors’ minds,” says Cingari.

People seek safety in the precious metal when they are concerned about losing real value from otherwise safe assets like cash and US government bonds, Cingari explains. These assets tend to decline in value when inflation expectations rise faster than nominal yields.

“We haven’t gotten there yet, but we’re not that far away,” he adds.

Another factor to consider is that gold is facing competition from digital assets led by Bitcoin, which has changed the market dynamics to some extent. “Some of the capital that may have previously flown to gold is now tied up in Bitcoin, which has unfortunately fared even worse,” Simply Wall St’s Bowman explains.

It should be noted that since Bitcoin emerged some 15 years ago, it has greatly outperformed most other asset classes, including gold.

Gold investment trends

Historically, investors buy gold to diversify a multi-asset portfolio to smooth risk and return and reduce overall losses when stocks, bonds, real estate and other assets fall. As we’ve established earlier, that strategy works better with a longer-term view.

Buying bullion bars or coins is one way to gain exposure to gold, but storage and insurance costs can be expensive. Another way to have physical possession of gold is through buying jewelry, though its demand has slumped since 2021, with weaknesses in key markets like China.

According to the World Gold Council’s data, jewelry consumption softened a fraction in 2022, falling 3% to 2,086 tons. However, the most recent quarter saw a modest year-on-year improvement in jewelry consumption despite a higher gold price environment.

On the other hand, demand for gold bars and coins grew 2% to 1,217 tons last year, and stayed strong through the first half of 2023. Demand growth reached 6% and 5% for the first two quarters of the year, respectively.

Overall, buying physical gold gives investors the flexibility to resell it when needed, though there is no guarantee that investors will get the same market price when they sell. Also, physical gold does not produce a yield while it is held.

For investors looking to avoid the hassles and drawbacks of owning physical gold, there are two other options to consider that also provide direct exposure to the metal: 1) buying shares in exchange-traded funds (ETF) that replicate the price of gold; and 2) trading gold futures and options in the commodities market.

ETFs can provide investors with a more liquid and low-cost entry into the gold market. SPDR Gold Shares (GLD), for instance, is one of the oldest ETFs of its kind, and can be bought or sold at any time throughout the trading day, just like any other stock. Each share of GLD represents one-tenth of an ounce of gold.

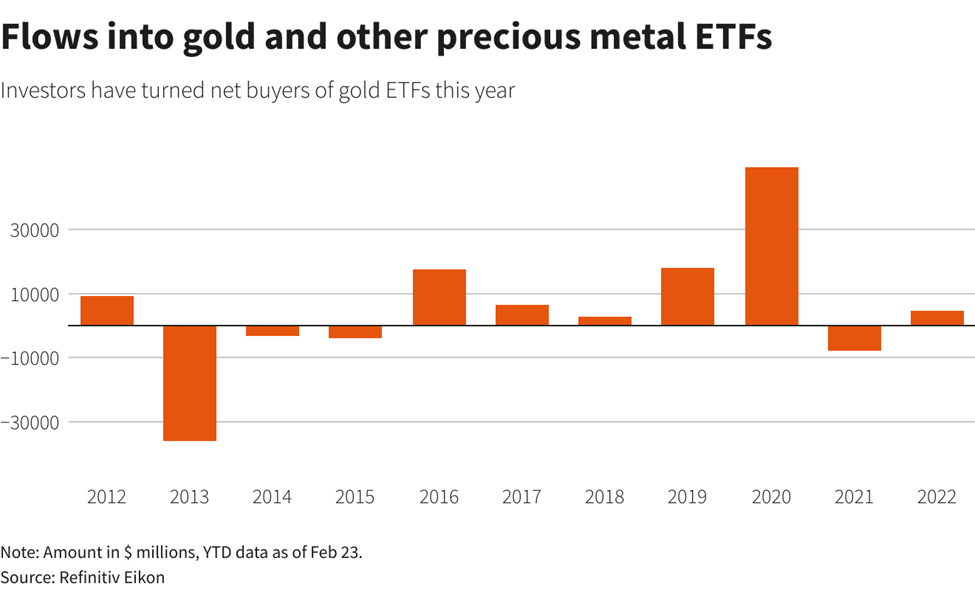

In 2020, gold-backed funds like GLD accounted for two-thirds of global net inflows for investment demand in the precious metal. During that year, gold ETF inflows reached $47.5 billion, almost double the previous record inflow set in 2016. However, investment in gold ETFs subdued over the last two calendar years, highlighting the weakness of the gold market.

For the more experienced investors who don’t want to risk a lot of capital, they can consider options on gold futures, or even options on a gold ETF. These contracts represent the right—but not the obligation—to buy or sell an asset (gold in this case) at a specific price for a certain amount of time.

In other words, they’re used to bet on gold’s future prices, and should your prediction turn out wrong, the maximum risk associated will only be the premium you paid to enter the contract.

What about gold stocks?

There’s also one last, but more risky, option — buying gold mining stocks. Compared with gold-backed funds, a miner’s performance depends on not just gold prices, but also the company’s reputation, production costs, reserves and exploration results.

Of course, one way to minimize the risk is to hedge your bet on more than one stock, or better yet, a basket of mining stocks. Like with the gold price, there are funds and ETFs that track the performance of gold mining companies.

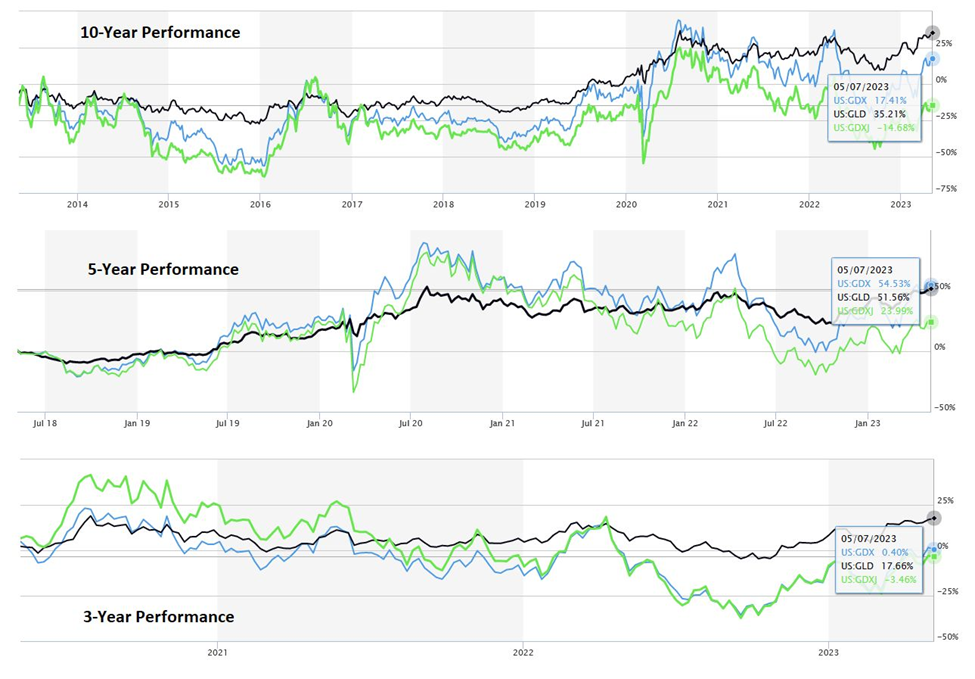

The biggest and by far the most popular is the VanEck Gold Miners ETF (GDX), which offers investors exposure to some of the largest gold mining companies in the world, such as Newmont and Barrick. Investors with a higher risk tolerance can also consider VanEck Junior Gold Miners ETF (GDXJ), which invests worldwide in small and mid-cap gold mining equities.

However, despite registering a notably higher volatility than gold-backed ETFs like GLD, the gold mining ETFs don’t always have the best performance (see charts above). This is usually the case in the medium and long term. For example, GDX is down 4.4% year to date, while GLD is essentially level. It is only in shorter periods of time that gold miners, specifically the ETFs that focus on large, stable gold producers (like GDX), can yield better results. But again, that applies to any risky asset.

According to John Hathaway and Shree Kargutkar, managing partners at Sprott Inc., the biggest reason for gold stocks’ underperformance is the implicit consensus that gold priced in the current neighborhood of $2,000 per ounce is not sustainable.

“We believe the notion that gold mining stocks offer perpetual optionality and leverage to still higher gold prices is heavily discounted, even dismissed when weighing their pros and cons,” they wrote in the Sprott Gold report.

Their article also cites the drop in the gold price after 2011 that doomed the industry to subpar returns on capital for the next five years, which led to the gold mining industry drastically cutting expenditures between 2015-2021.

Although the capex spending began to recover in 2022, the level (not inflation-adjusted) still fell far short of the peak 10 years prior, despite current global mine production being ~20% greater than a decade ago, the Sprott partners said.

“We believe that this capex drought means that capacity added during the industry’s nuclear winter (2013-2020) translates into unrecognized scarcity value. In all probability, the replacement cost of existing capacity markedly exceeds the stated book value. The hurdle rate to build new mines will most likely require significantly higher metal prices,” they wrote.

Moreover, the overwhelming success of funds backed by gold has cannibalized demand for gold mining shares. Before the launch of GLD in 2004, equity investors bullish on the gold price had no alternative but to invest in gold mining shares. Since then, their investment strategies have changed.

This is evident from the increased outflow of capital from gold mining equities. In 2010, the aggregate market capitalization of gold mining equities stood at roughly $300 billion, but by the end of 2022, this figure had dwindled to approximately $260 billion.

Ultimately, the performance of gold stocks is inextricably connected to the price behavior of the metal, in both the present and the future. In Sprott’s view, a bullish outlook for gold would far outweigh any other rationale for owning them.

Verdict on gold stocks

As the Sprott article states, the response of gold mining equities to the bull market in bullion has been disappointing. “What appears to be lacking is a decisive bullion price breakout that leaves the psychological $2,000 per ounce threshold in the rearview mirror,” it states.

However, there is definitely hope for those bullish on gold stocks, as explained by Sprott below:

“We anticipate that such a breakout is on the horizon, potentially in the not-so-distant future … until it materializes, it remains a macroeconomic speculation entertained by few.”

“The time for accumulation is now, not after the investment case becomes obvious based on a new gold price paradigm that $2,000 is the floor, not the ceiling. A major barrier to the mean reversion thesis for mining stocks is the confusion between nominal and inflation-adjusted prices.

“Based on recent history, the superficial view is that when the metal price approaches the magic number of $2,000 per ounce, the potential for further upside is exhausted and a signal to initiate short positions. On an inflation-adjusted basis, today’s $2,000 gold price is ~30% below the peak in 2011 and ~50% below the peak of $800 in 1980. Fixation on nominal prices ignores the fact that macroeconomic realities in favor of gold have improved significantly since previous peaks.”

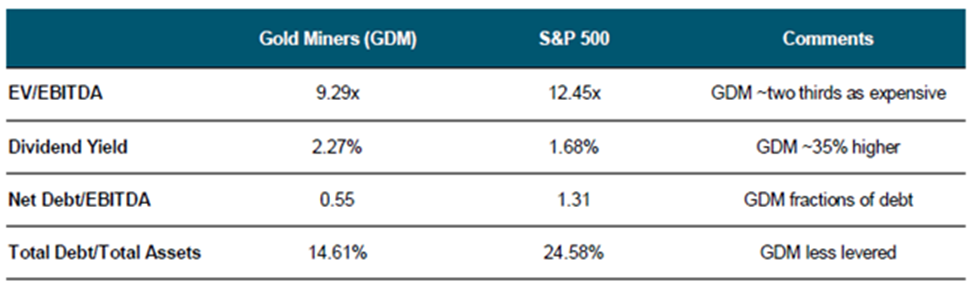

In layman’s terms, gold mining stocks are undervalued on a relative and absolute basis. Gold mining equities are trading multiples lower than the S&P 500 Index and with greater profitability and lower leverage, as shown in the table below.

As Sprott pointed out, gold mining equities have two things going for them. First, they have quietly become very cheap stocks, are seriously unloved and represent a contrarian’s delight. Second, they offer low-risk exposure to what we regard as the very likely prospect of the continuing and possibly accelerating downgrade of the USD.

Conclusion

The relatively weak performance in recent months is mostly a reflection of inflation being held under control and the global economy leaning away from a recession. Bullion, after all, is considered the best hedge against recession and inflation.

However, there is value to be had still, simply because gold, as an investment asset, can offer diversification in the long run. Also, many of the instruments tied to the metal can either help to track/speculate on its price or provide far higher returns but with increased volatility (i.e. stocks).

Looking forward, there’s still a distinct possibility that gold will break out once again and set new all-time highs. The reason for that will be a gradual weakening of the US dollar as inflation cools.

As we’ve pointed out many times before, the USD is at risk of losing its dominance in the world’s capital markets. The clue is found in how central banks are buying up gold as an alternative reserve asset..

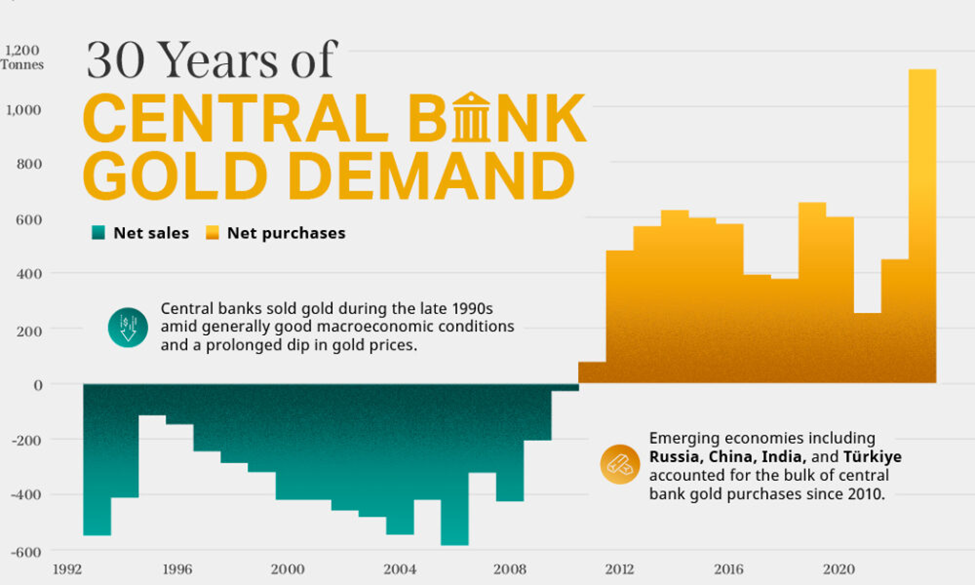

As shown in the chart below, there’s a stark contrast between how global central banks approached gold in the 1990s and early 2000s, versus the years that followed the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Since 2010, central banks have turned from net sellers into buyers on an annual basis. In 2022, central banks added a whopping 1,136 tonnes of gold worth some $70 billion to their stockpiles, by far the most of any year in records going back to 1950.

The strong demand from central banks continued into this year. The H1 2023 gold purchase figure also set a record despite three straight months of net selling during March-May. Purchases have since picked up, and according to the WGC, “the latest data does seem to support our view that the longer-term buying trend remains in place.”

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Christina Dian Parmionova

Demand for gold bars and coins grew 2% to 1,217 tons last year, and stayed strong through the first half of 2023.