Iron ore market regains composure, futures curve may be too pricey

There are emerging signs that stability is starting to return to the iron ore market, suggesting that spot prices may have peaked and the forward curve may look too rich.

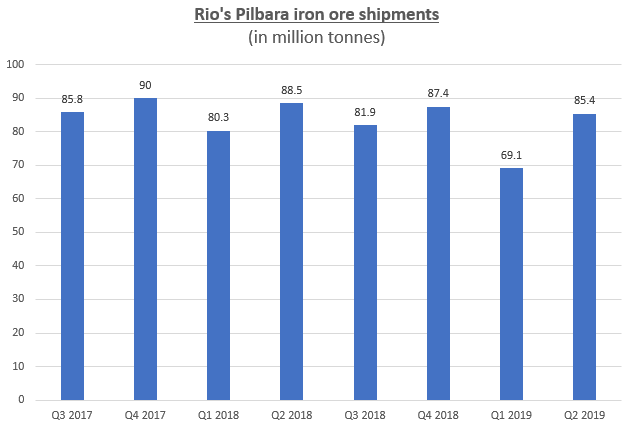

Two of the world’s top three miners of the steelmaking ingredient, Rio Tinto and BHP Group, released production numbers that suggested the worst is over for the weather-related supply disruptions that curtailed output at the companies’ Australian mines in the first quarter of 2019.

Rio and BHP released production numbers that suggested the worst is over for the weather-related supply disruptions that curtailed output at the companies’ Australian mines in the first quarter of 2019

There is also some indication that shipments from the other top producer, Brazil’s Vale, may be starting to recover to more normal levels after exports were hit by mine closures for safety checks after a dam failure killed more than 230 people and left dozens missing in late January.

Separately, on the demand side, authorities in China – which buys about two-thirds of global seaborne iron ore – have signalled increasing unhappiness about the 60% price rally since Vale’s dam disaster on Jan. 25.

A meeting last week between government departments, top steel mills, domestic trading houses, industrial associations and the Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE) saw the government promise to keep “order” in the iron ore market, according to sources who attended the meeting.

What this means in practical terms is likely a tightening of money flows into the iron ore futures traded on the DCE, as well as behind-the-scenes pressure on market participants to keep a lid on price gains.

Inventories stabilize

A further factor is that the sharp decline in China’s port inventories appears to have stopped, with stockpiles holding around the 115 million tonne level for the past three weeks.

While it’s true that this is still a dramatic and rapid drop from this year’s peak – 148.9 million tonnes in early April – it’s worth noting that the decline in inventories roughly corresponds to the volume lost to the seaborne market in the first half from Brazil’s woes and Australia’s weather.

If port inventories continue to stabilise around current levels, that would be a convincing sign that the worst of the supply crunch is in the rear view mirror.

Certainly, Rio Tinto and BHP expect their output to show some recovery in the second half of the year.

BHP expects modest growth in production in the 2019-20 financial year that started this month, forecasting output of 273 million tonnes to 286 million, a 1-6% increase from the year that ended on June 30.

Rio Tinto and BHP expect their output to show some recovery in the second half of the year

Rio Tinto maintained its forecast for 2019 exports in a range between 320 million tonnes to 330 million. That’s below the 338.2 million it shipped in 2018, but would mean a considerably improved second half of 2019, given that first-half output was 154.5 million tonnes.

The reports from Rio Tinto and BHP suggest that both will be adding to their output in the second half of 2019 from the first, which may put some downward pressure on prices.

The ‘known unknown’ for supply is how quickly Brazil can return to normal output: There are signs of recovery in exports, but there is still some way to go.

Vessel-tracking and port data compiled by Refinitiv show Brazil exported 30.34 million tonnes in June, the most in a month since December’s 35.96.

Shipments for July are tracking at about 1 million tonnes per day, suggesting June’s pace is at least being maintained.

However, Brazil’s exports traditionally pick up in the second half of the year and it will be key to see if the country can get back to levels closer to 33-34 million tonnes per month.

Even if Brazil’s exports do remain slightly below normal, it may be the case that the iron ore forward curve is currently too optimistic.

The Singapore Exchange front-month contract closed at $121.24 a tonne on Wednesday, while the six-month contract was at $100.52 and the 12-month at $89.52.

This shows traders do expect prices to moderate, but not currently to the extent forecast by the Australian government, which said in its June quarterly report that iron ore on a free-on-board basis in Australia will average $70 a tonne in the 2019-20 fiscal year.

The Singapore price is for ore delivered to China, but even allowing for shipping costs of $7-$9 a tonne, the futures curve is still looking pricey.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters)

(By Clyde Russell; Editing by Kenneth Maxwell)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments