Inflation is the fourth horseman

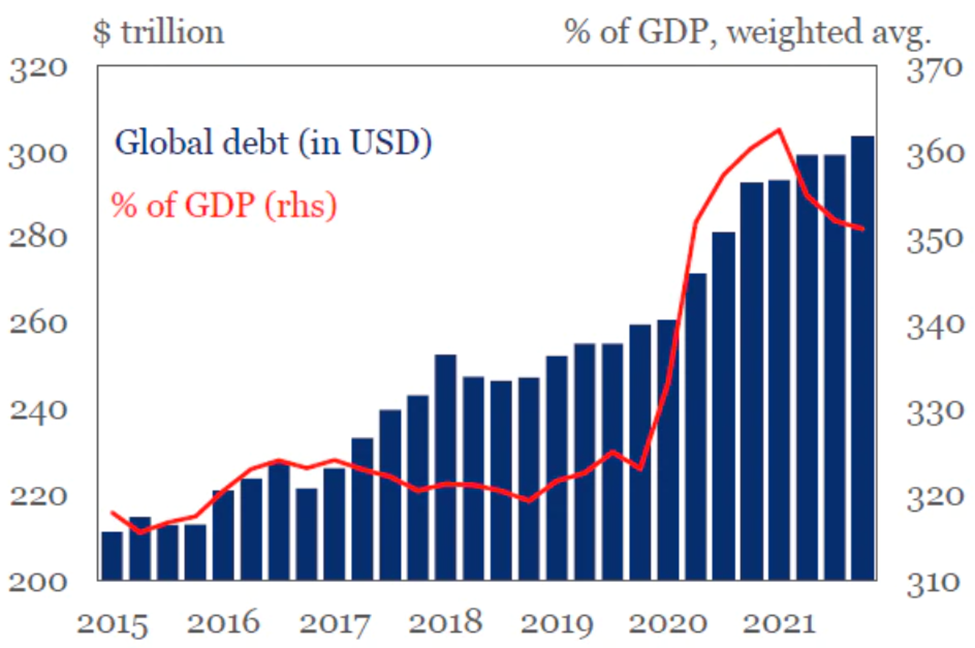

Over the past year, relentlessly rising interest rates (because of the global fight on inflation), are putting pressure on borrowers, who are reportedly deeper in the red than ever before.

Rising interest costs are “a slow-moving train for consumers and companies, just like for governments,” Bloomberg quotes Sean Simko, global head of fixed-income portfolio management at SEI Investments. “At some point you are going to be watching it slowly creep up. And then all of a sudden it’s going to be in your face. And then it’s going to be too late.”

While rich countries can afford to pay more interest on their debts, at least for awhile, it’s the poorer countries that are suffering most.

Developing-world economies that borrowed heavily in dollars when interest rates were low, are now facing a huge surge in refinancing costs. They are not only facing higher interest rates, but have to use more of their own currencies to buy dollars. The buck has been climbing on the back of six consecutive Federal Reserve interest rate increases.

A wave of defaults across developing nations would have major implications for the global economy, just as Asian debt contagion in 1997 spread to Russia and Latin America.

If you think this is theoretical, note that Sri Lanka and Zambia have already defaulted, and Egypt and Pakistan are among a handful of others at risk of following suit. More than half of low-income countries are in debt distress or on the brink of it, Bloomberg said.

Among developed economies, Italy is the most at risk. The Italian government’s interest payments will exceed 7% of GDP by 2030, which by Bloomberg Economics’ estimates, is unsustainable.

From 2014 to 2018, central bank interest rates worldwide were steady at about 2.5-3%, before rising to 3.5% in 2019. They fell to 1.5% in 2020 as a reaction to the covid-19 crisis, and have since climbed to 4.5%, as central banks continue to try and control inflation.

For the United States, whose national debt is currently $31.3 trillion, the interest alone, which is short term and rolling over, will be $1,395 trillion, annually.

Globally, the interest on $300 trillion (for round numbers) of debt, works out to over $13 trillion! Per year. Another way to look at this, is the global economy in 2022 is worth $100 trillion. Every year, 13% of that will go to paying the interest on the debt.

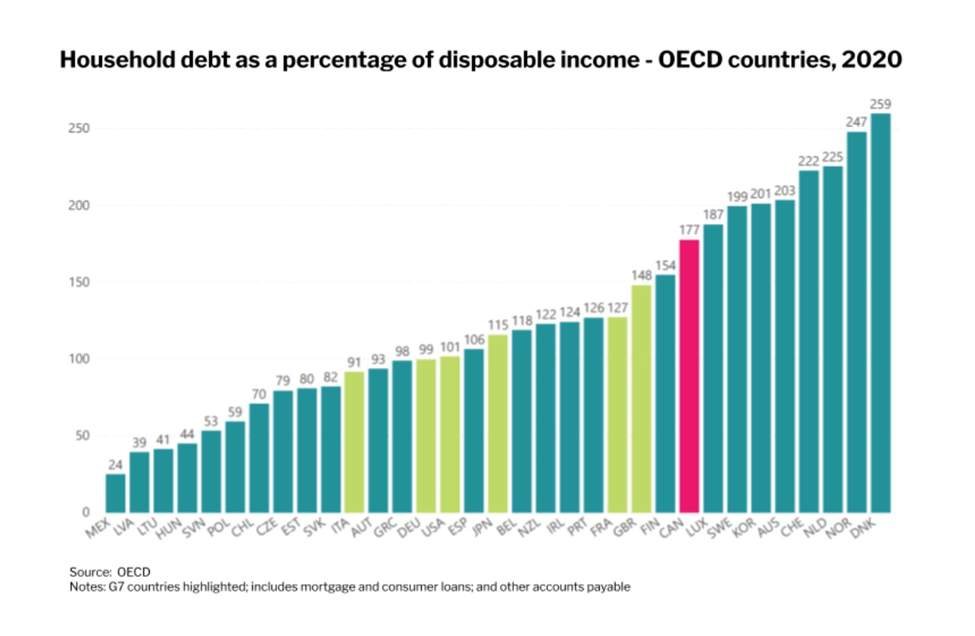

Let’s break down this colossal debt burden, starting with household debt. Consumer spending makes up about 70% of the global economy, so high levels of credit card debt, bank loans, student loans, lines of credit, etc., represent a significant danger.

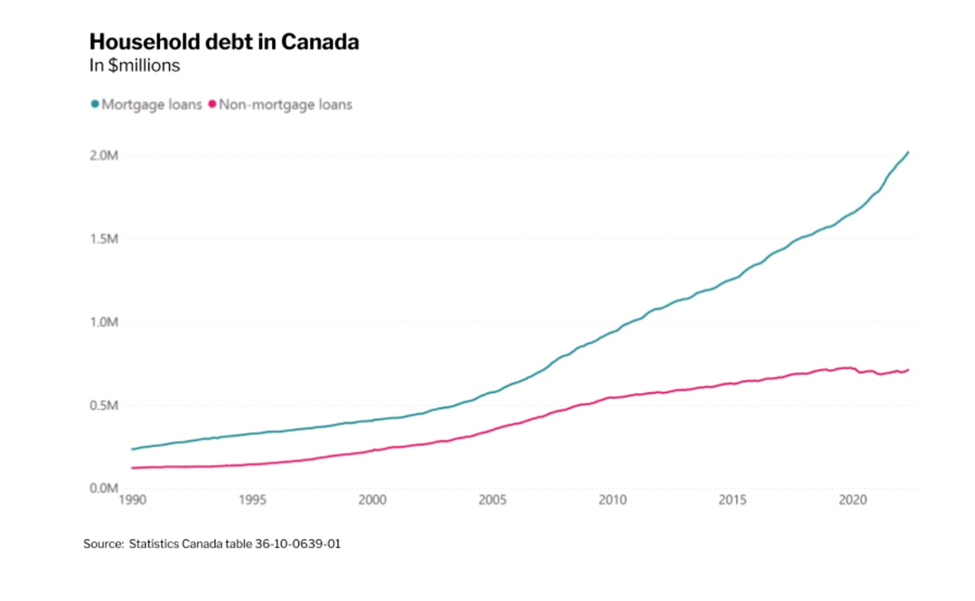

Bloomberg says trouble is brewing most in countries that have a large share of variable-rate mortgages (as opposed to fixed mortgages), and where households have kept adding debt instead of paring it back. The poster-children are South Korea, Australia, and perhaps surprisingly, Canada.

New research from the Bank of Canada found that variable-rate mortgages now account for one-third of outstanding mortgage debt, up from about one-fifth at the end of 2019 (Financial Post, Nov. 22, 2022). Moreover, about half of these mortgages have reached their trigger rate, which is the point where additional payments may be needed. This number represents about 13% of all Canadian mortgages.

In fact Canadian households are among the most indebted in the developed world. 2020 household debt in Canada was easily the highest of G7 countries, at 177.3% of disposable income, followed by the UK at 147%. Household debt in the US that year was 101%. Within the 38-member Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canada ranks ninth in terms of average household debt. (Business Council of Alberta)

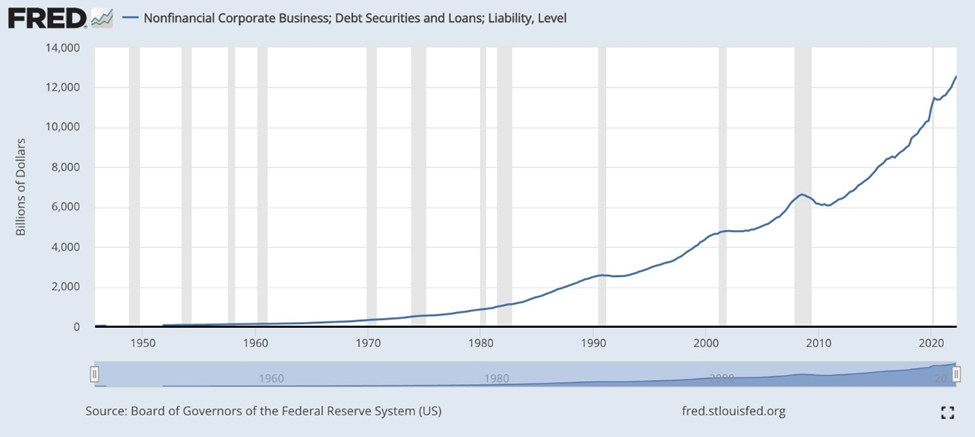

Of course it isn’t only governments and households that have been spending now and paying it back later. Corporate debt is also significantly on the rise. The IIF found that businesses outside of the finance industry are neck and neck with governments, as the biggest borrowers of the cheap-money era.

2020 set a record for corporate debt issuance with $2.28 trillion of bonds and loans, with the non-financial debt and loan market now over $12 trillion, according to Federal Reserve data.

Wikipedia describes the corporate debt bubble, excluding that of financial institutions, that grew after the financial crisis, when global corporate debt went from 84% of GDP in 2009 to 92% in 2019, in the world’s eight largest economies — the US, China, Japan, UK, France, Spain, Italy and Germany.

While US corporate debt in 2019 reached a record 47% of GDP, two-thirds of global growth in corporate debt occurred in developing countries, in particular China; the value of Chinese non-financial corporate bonds increased from $69 billion in 2007 to $2 trillion in 2017.

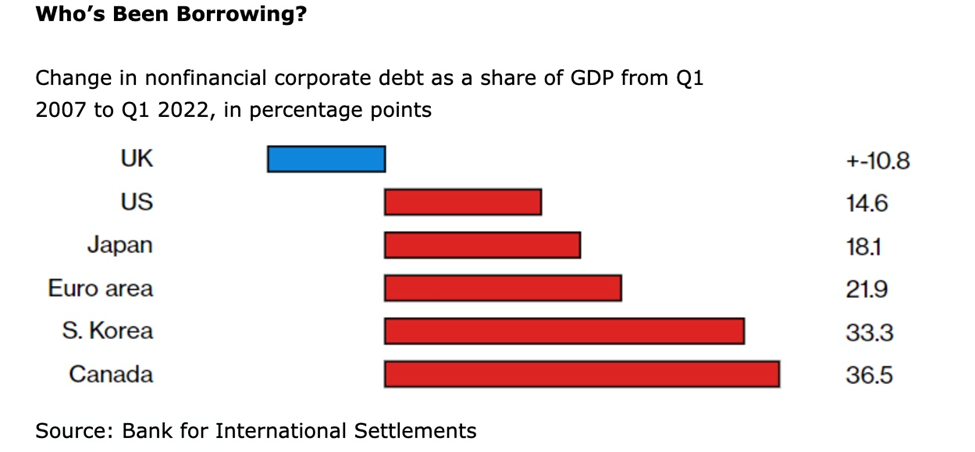

Another Canadian surprise: The graphic below shows Canada’s non-financial corporate debt from the first quarter of 2007 to Q1, 2022, as a share of GDP, grew 36.5%, more than South Korea, the euro area, Japan, the US and the UK.

Like household and government debt, corporate debt faces a reckoning when it comes to higher interest rates. The IIF forecasts that, in an economic downturn as severe as the 2008 financial crisis, $19 trillion in debt would be owed by non-financial firms without the earnings to cover the interest payments. These companies are sometimes referred to as “zombies”.

Bloomberg writes:

This year’s surge in borrowing costs may add to the ranks of businesses that only earn enough cash to service their debts… By some measures, about one-fifth of publicly traded corporations already fit that definition when interest rates were low. With debt costs now surging, more companies are likely to join them. And some that were already in the zombie category may go bust.

“This looks a lot to me like the internet bubble,” Scott Minerd, global chief investment officer at Guggenheim Investments, said on Bloomberg Television. Even though plenty of companies now are making money, “we have a lot of companies that aren’t.”

Worldwide, Moody’s Analytics Inc. reckons that default rates on what it calls “speculative grade” debt—what the financial world calls “junk”—will almost double next year. In the $6.7 trillion market for high-grade US corporate bonds, there are signals that defaults could be by far the worst of the past five decades, according to an analysis by Barclays Plc.

Investors are even more worried about Asia, where the dollar’s strength has made dollar-denominated debt more expensive. Prices of bonds issued by real estate developers in Vietnam and Indonesia have swooned, while defaults in China’s property sector are at record levels. In South Korea, the company that built the local Legoland theme park missed a debt payment in October, a rare event in that country…

For smaller businesses in the US, which tend to borrow from banks at floating rates, the worst is yet to come, says Aneta Markowska, chief financial economist at Jefferies LLC. They’ll likely be forced to lay off workers as the Fed’s rate hikes peak early next year. “It’s in the first quarter when I’d expect to see more cracks, as these small businesses start to see the pain of higher rates,” she says.

In fact the total amount of corporate debt is much higher than the above-mentioned figures would indicate. The Bank of International Settlements, via Yahoo Finance, flagged a hidden risk to the global financial system embedded in the $65 trillion of dollar debt being held by non-US institutions via currency derivatives.

The lack of information about this “huge, missing and growing” dollar debt held by institutions outside the US, like pension funds, is making it harder to anticipate the next financial crisis.

“Thus in times of crises, policies to restore the smooth flow of short-term dollars in the financial system — for instance, central bank swap lines — are set in a fog,” the report said.

It also notes the total amount of dollar debt from the derivatives stands at more than $80 trillion, exceeding the combined value of dollar Treasury bills, repurchase agreements and commercial paper.

Banks headquartered outside the US carry $39T of this debt, more than double their on-balance sheet obligations and 10 times their capital.

Deteriorating economy

Higher and ultimately, unsustainable debt servicing costs, are central to the contention that there will, in economist Nouriel Roubini’s words, a “long and ugly” recession in 2023.

Indeed the November stock market bounce appears to be over, with equities heading for a second straight day of declines, Tuesday. At time of writing, the Dow had dropped another 500 points, bringing two-day losses to nearly 1,000 points. All three US indices were down in early afternoon trading, with the Wall Street Journal reporting that investors are weighing fears that the Federal Reserve will keep interest rates higher for longer (a decision will be made next week), against optimism over China easing some covid-19 restrictions.

Remember, the Buffett Indicator shows stocks are still overvalued, meaning they could fall further during what’s left of Q4 and into the new year.

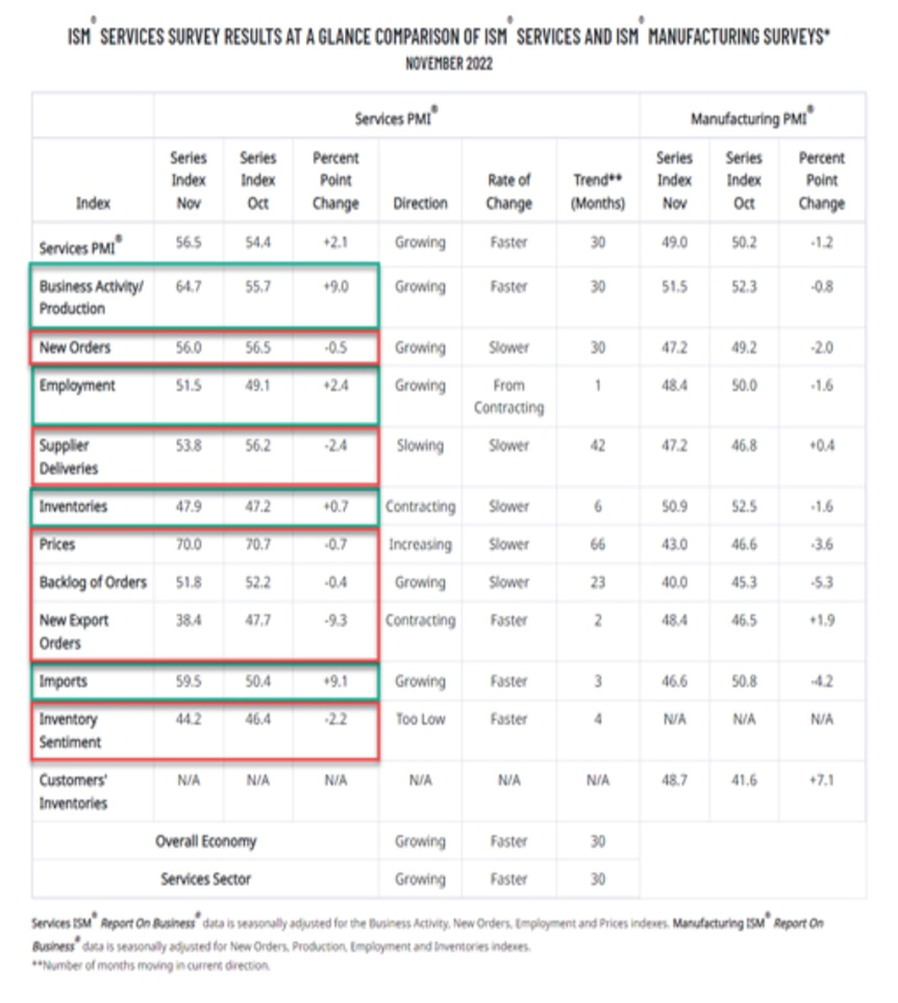

Economic indicators aren’t giving much to hope for. After Dec. 1’s release of an ugly set of manufacturing data for November, S&P Global’s Services PMI fell from 49.3 in September to 46.2 in November. It was the latter’s fifth straight month of contraction.

Economic activity in the manufacturing sector contracted last month for the first time since May 2020, after 29 consecutive months of growth, the nation’s supply executives said in the latest Manufacturing ISM Report On Business. (PR Newswire, Dec. 1, 2022)

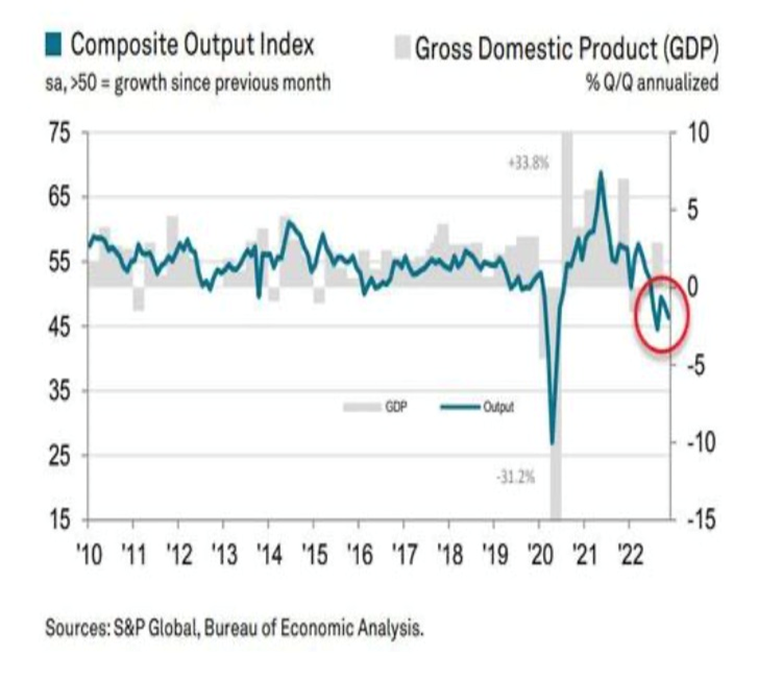

Zero Hedge noted that, despite a hotter-than-expected ISM Services PMI, which remains the only signal still showing expansion (+50), new export orders collapsed, and the S&P Global US Composite PMI Output Index posted 46.4 in November, down from 48.2 in October to signal a solid decline in private sector business activity.

Chris Williamson, chief business economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said: “The survey data are providing a timely signal that the health of the US economy is deteriorating at a marked rate, with malaise spreading across the economy to encompass both manufacturing and services in November.”

The survey data are broadly consistent with the US economy contracting in the fourth quarter at an annualized rate of approximately 1%, with the decline gathering momentum as we head towards the end of the year.

“There are some small pockets of resilience, notably in the tech and healthcare sectors, but other sectors are reporting falling output amid the rising cost of living, higher interest rates, weaker global demand and reduced confidence. Struggling most of all is the financial services sector, though consumer-facing service providers are also seeing a steep fall in demand as households tighten their budgets.

“A striking development is the extent to which companies are increasingly reporting a shift towards discounting in order to help stimulate sales, which augurs well for inflation to continue to retrench in the coming months, potentially quite significantly.”

It appears all but certain the world economy will enter a recession within the next six to 12 months. The warnings are written in the inverted yield curve (an extremely reliable recession indicator), stagnant US manufacturing data, and high debt levels among consumers, which make up 70% of the global economy. The latter is a major concern because it ups the risk of bankruptcies, delinquencies and forced stock selling, amid higher interest rates.

On Monday it was reported that the Canadian yield curve — the difference between benchmark 2-year and 10-year debt — spread to its widest point since the early 1990s — another warning that a recession is on its way.

The yield on the 2-year reached 100 basis points (i.e. 1%) above 10-year bonds, at just under 3.8%.

The yield curve inversion — when investors rotate money into longer-term bonds due to near-term economic concerns, pushing short-term yields higher — is a global phenomenon, as markets price in further rate hikes from central banks working to slow inflation.

“The inversion is telling us that current policy rates and their near-term expectations are entirely unsustainable over the long run,” Taylor Schleich, a strategist at National Bank of Canada, said by email. He sees the situation persisting at least until investors see an endpoint for the Bank of Canada’s rate hikes.

While most economists don’t see a major downturn ahead in Canada, growth is expected to stall in 2023, with the economy potentially entering a technical recession. (Bloomberg, Dec. 5, 2022)

Conclusion

According to the Institute of International Finance, the total owed by households, businesses and governments now stands at $300 trillion.

The debt crisis is global, it threatens to envelope businesses, governments and consumers. Those that borrowed heavily when interest rates were low are now facing a huge surge in refinancing costs because the fight against inflation is forcing interest rates to rise. Half of the poorest countries are in, or at high risk of, debt distress. Sri Lanka and Zambia have already defaulted.

The linkage between inflation, rising interest rates and debt is of upmost importance because inflation is the fourth horseman of an economic apocalypse, accompanying stagnation, unemployment and financial chaos.

(By Richard Mills)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

2 Comments

BOB HALL

Good read! One of the most significant issues in the big three consumer debtors is the governments have sent a poor signal about debt. They continue to overspend (mostly on non essentials) and the citizens follow suit. S Korea, Canada and Australia are not likely to exhibit debt distress due to the nature of the economies. But the citizens do not have the same depth to cover increased interest on their debt.

Foolish government spending will not stop as it is the basis of re-election. The citizens will hurt for two or three years until the economy rights itself. One can only hope governments decide not to help!

Dr. Hujjathullah M.H.B. Sahib

How can the U.S. interest pay.ment be US$ 1,395 trillion annually when the global interest payment is just around U.S.$13 trillion per year ? Quite illogical isn’t it !