Indonesia pressures commodity firms with earnings rule

Indonesia plans to force commodity firms to keep their export earnings onshore for at least a year, tightening an existing requirement for a sector already facing mounting regulatory uncertainty.

The policy, due to take effect on March 1, is aimed at bolstering Indonesia’s foreign-exchange reserves and supporting the rupiah. Exporters, however, have complained it will impact their ability to manage cash flow and force them to take out larger loans to finance everyday expenses. Currently, exporters are required to keep 30% of proceeds in Indonesia for at least three months.

“A sudden move could shock businesses and impact their cash flow,” said David Sumual, chief economist at Bank Central Asia. “If they’re unprepared, it will be challenging.”

The Indonesian rupiah has been under pressure from a resurgent dollar, weakening more than 7% since the end of September despite multiple interventions by the central bank. Bank Indonesia’s surprise interest rate cut last week added to the country’s predicament.

But the new rule comes as Indonesia’s natural resources sector, the cornerstone of its economy, faces other sudden shifts in policy under recently inaugurated President Prabowo Subianto. The country is weighing cuts to nickel mining quotas to boost prices, Bloomberg reported last year, potentially worsening global shortages.

Indonesia’s biggest copper mine, owned by Freeport McMoran Inc. and a state-owned partner, is currently unable to ship its output overseas as ministers prevaricate over whether or not to temporarily relax a ban on exports.

While the new government had already signaled its intent to extend the foreign-exchange lock-up, the scale of the changes has taken exporters by surprise. It marks a shift in approach from the more measured policy of Prabowo’s predecessor, Joko Widodo, who relied on tax incentives and well-telegraphed export bans to stimulate investment into the processing of raw commodities.

It also comes at a time when coal and nickel, two of Indonesia’s highest-earning commodities, are trading near multi-year lows. Both sectors will be affected by the measure, as well as the country’s huge palm oil plantations.

“In the mining and plantation sectors, such a retention rule could trigger potential layoffs due to unhealthy company cash flows,” Sutrisno Iwantono, head of public policy division at the Indonesian Employers Association, said in statement. “There are also fears of a knock-on effect of reduced coal and mineral production.”

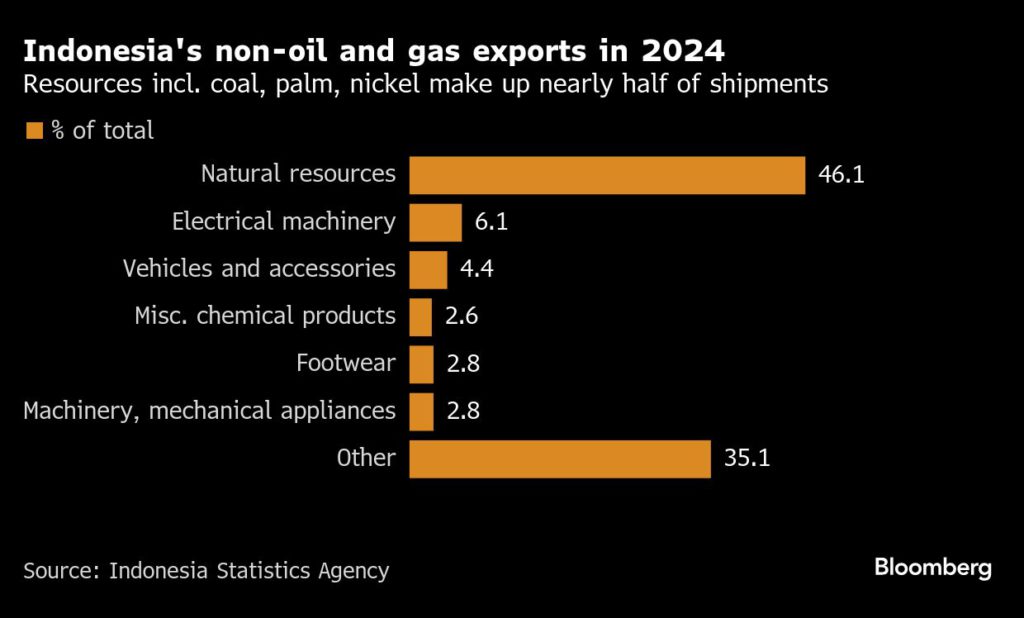

The commodities covered under the new rule account for nearly half of Indonesia’s non-oil and gas exports. Shipments of mining, agricultural, forestry and fisheries products reached almost $115 billion last year.

Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto said exporters can use their foreign currency proceeds to pay state levies, taxes, and dividends, according to a statement from the presidential palace. They are also encouraged to convert their funds into rupiah and use a specific deposit instrument as back-to-back collateral for loans from banks or Indonesia Exim bank, it added.

“We are already supporting the program by providing FX deposit instruments at attractive interest rates and hedging through FX swaps,” Bank Indonesia Governor Perry Warjiyo said on Wednesday. He added BI is preparing two foreign currency-denominated securities, known as SVBI and SUVBI, in which exporters can place their earnings, in addition to term deposits and swaps offered under the current policy. The instruments can be traded in the secondary market.

(By Eddie Spence and Chandra Asmara)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments