India considers net-zero goal around 2050, a decade before China

Top Indian government officials are debating whether to set a goal to zero out its greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century, an ambitious target that would require overhauling its coal-dependent economy.

Officials close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi are working with senior bureaucrats and foreign advisers to consider ways to meet the 2050 deadline, according to people familiar with the matter. A 2047 target is also being considered, they said, to mark the centenary of India’s independence from British rule. The people asked not to be identified because the discussions are private.

India, the world’s third-biggest emitter, has come under pressure to make a net-zero pledge ahead of global climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland, this year. Signatories of the Paris Agreement are expected to boost their commitments to slow global warming, and China — the biggest polluter and a rival of India — won international praise for setting a 2060 net-zero target in September.

The timing and scope of India’s announcement could depend on pledges other nations make on April 22, when U.S. President Joe Biden is set to gather world leaders for an Earth Day summit. The event is the first such meeting Biden will host as president, and he’s asked climate envoy John Kerry to secure fresh commitments from attendees.

“Every single country has to step up ambition,” Kerry told the BBC during his visit to the U.K. earlier this month. He explicitly included India while singling out “the 20 countries that are the equivalent of 81% of global emissions.”

The Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of External Affairs and Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change in New Delhi didn’t immediately respond to requests seeking comment.

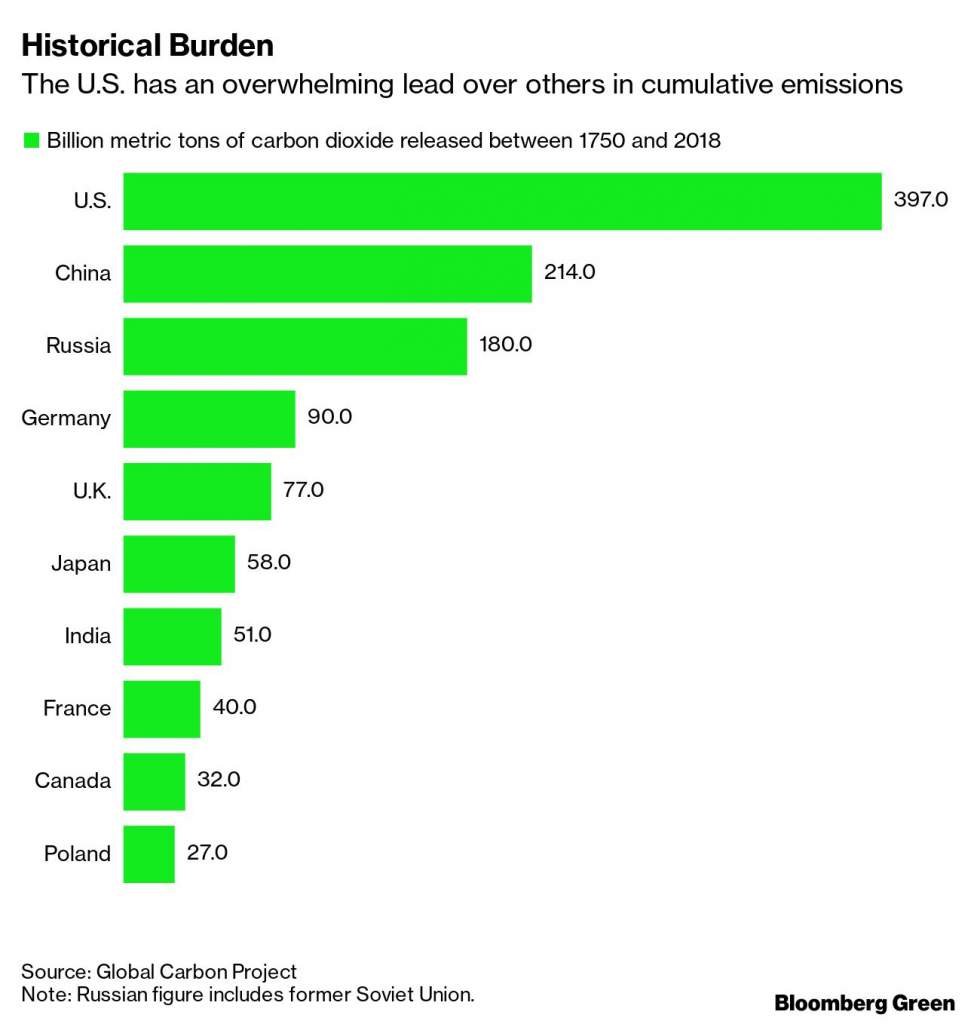

As of 2018, India ranked seventh among top historical polluters, after the U.S., China, Russia, Germany, the U.K. and Japan

Once the U.S. adopts a widely anticipated net-zero goal, nine of the 10 largest economies will have made pledges to neutralize about 60% of global emissions. If India does so, too, it would mark a significant step in the fight against climate change — though experts warn that a 2050 target will be extremely difficult to achieve.

There are signs that support is growing domestically for India to set a net-zero goal.

Jayant Sinha, a member of parliament with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, said on March 12 that he had submitted a private members’ bill in the parliament that would make a 2050 target legally binding. On March 16, T.S. Singh Deo, a cabinet minister for the eastern state of Chhattisgarh, said the area’s health sector is setting a 2050 net-zero target.

Big hurdles

Non-governmental institutions in India have started using models to work out potential pathways to net-zero emissions, two of the people familiar said, but the research is at an early stage and does not cover the entire economy.

The country needs more information before it can credibly set such a target, according to Navroz Dubash, a professor at the Centre for Policy Research and editor of the book ‘India in a Warming World’. “We don’t know exactly how we will do it and what are the potential trade-offs with development objectives.”

The International Energy Agency’s modeling shows a potential path for India to approach net-zero emissions in the mid-2060s. That’s based on the think tank’s Sustainable Development Scenario, which meets the Paris Agreement objective of keeping global warming to “well below 2°C,” but does not reach the more ambitious goal of keeping it to 1.5°C. A new model for 1.5°C is set to be released in May and may show possible ways for all countries, including India, to zero out emissions sooner.

Over the past decades, developing countries have contributed far less greenhouse gases to the atmosphere than nations that industrialized earlier. As of 2018, India ranked seventh among top historical polluters, after the U.S., China, Russia, Germany, the U.K. and Japan.

Even the Paris accord acknowledges this reality, noting that nations have “common but differentiated responsibilities.” The clause has been used to support arguments that rich countries should cut their emissions faster, allowing poorer countries to use fossil fuels for a bit longer to help them achieve the prosperity which the West has enjoyed for decades.

“For countries such as India, the most important thing is to achieve the greatest development for the fewest additional emissions,” said Dubash. Instead of setting a distant net-zero goal, India should “figure out ways to avoid locking in high-carbon infrastructure,” he said. For example, the nation hasn’t set a target for peaking its use of coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Internal debate

Some Indian officials want to see what the U.S. says about the Paris goals at the April 22 meeting before making any commitment, including whether Western nations change the Paris goalposts in any way, the people said.

India’s existing commitments are already relatively ambitious, with nonprofit Climate Action Tracker giving it the best rating among large economies. The country wants to expand renewable power to 450 gigawatts by 2030, almost five times existing capacity, and to cut emissions intensity by at least a third from 2005 levels by the end of the decade.

Achieving net-zero emissions would require India to set even more aggressive renewable energy targets, electrify not only its transport sector but most industrial processes, find solutions for hard-to-abate sectors like construction and agriculture, and dramatically boost commitments to reduce consumption of almost every conceivable product.

With a growing population and still-industrializing economy, a net-zero goal for India will be a much bigger lift than for most economies. “The country may not agree to any net-zero targets by 2050 without external financial support,” said BloombergNEF analyst Shantanu Jaiswal.

Modi will also need to navigate potential pushback from inside his government. India’s Power Ministry previously delayed a drive to cap toxic emissions from power plants, arguing the sector couldn’t meet an original 2017 deadline to make improvements on discharges of pollutants like sulfur dioxide and mercury.

There is no consensus among ministries over the net-zero target, the people familiar said, with some officials arguing that India shouldn’t bow to pressure given its fossil fuel use is set to rise in the coming decade.

Still, Modi has surprised his own government before with policy announcements that have had wide-ranging impact. In 2016, he shocked the nation by banning some 86% of currency notes overnight in a landmark demonetization program, while last year he gave no warning in locking down the country to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

While a net-zero goal would offer clarity on India’s climate stance, it won’t succeed without short-term targets, said Jonathan Elkind, a senior research scholar at Columbia University. Without clear policy routes, he said, “any long-term goal will remain elusive.”

(By Archana Chaudhary, Akshat Rathi and Rajesh Kumar Singh, with assistance from Jessica Shankleman and Abhay Singh)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments