How solar roofs are being used to power electric cars

Every two years, engineering students from across the US compete in the American Solar Challenge, where around 10 schools cobble together a car designed to go as far as possible, powered exclusively by the sun. In 2022, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology took the top prize with a car that looks sort of like a ping-pong table sprouted wheels. On its best day, the Nimbus made it an impressive 869 miles (1,398 kilometers), roughly the distance from New York to Milwaukee. Of course, there are just a few impracticalities to contend with: The Nimbus can’t carry a passenger, for one, let alone a haul of groceries.

The quest to develop a solar-powered car that is at once functional, useful and practical has stumped more than the young wizards at MIT. In February, Sono Group NV said it would abandon its Sion solar-electric car after failing to raise enough money for the project. A month earlier, Dutch startup Lightyear suspended production of its €250,000 ($264,450) solar car and filed for bankruptcy. (Both declined interviews for this piece.) California’s Aptera Motors, while happy with its three-wheeled solar-powered machine, has struggled to complete a crowdfunding campaign to get it into production.

For about 40 years, car companies, startups and DIY enthusiasts have been pursuing the plug-less electric car, one that could wirelessly recharge via photons. But as logistical and economic hurdles continue to stymie those projects, the more immediate future of solar-powered vehicles is becoming clear: smaller, lighter, cheaper systems built to subtly augment electric driving, rather than power it in full. This practical approach is the dad jeans of solar driving, and in a couple of years it could be everywhere.

The Hyundai Sonata isn’t particularly fast or large; it’s not even entirely electric. Cars don’t get much more milquetoast than this hybrid sedan, which has been around in some form since 1985 — except, that is, for the Sonata’s roof, which on newer models shimmers like fish scales. A closer look reveals that the roof is veined with a sheet of photovoltaic cells that casually, and very slowly, trickle about two miles of extra range a day into the car’s hybrid system, depending on cloud cover.

Toyota, too, sells a solar roof as a $610 add-on option for its Prius hybrid. At that price, the company doesn’t expect many customers to spring for it, though those playing a very long game might be inclined to. The Prius panels make for about 776 sun-powered miles a year, or roughly 14 gallons of gas. At current petrol rates, the roof pays for itself in about 13 years. Toyota says it’s now considering a similar system for the bZ4X, its new all-electric vehicle. Hyundai, meanwhile, is drawing up plans to add solar panels to the Ioniq 5, its breakout EV, which starts at $41,450.

“This is kind of a ‘shrug, why not?’ topic,” says BloombergNEF analyst Jenny Chase. “Cars of the future will have a bit of solar on the roof as standard.”

Even Elon Musk is on board. The Tesla chief executive has said — or, tweeted — that buyers of his long-promised Cybertruck will be able to add solar as an option, integrated into the cover of the pickup bed and possibly as unfolding “wings.” Musk has also said a car is one of the least efficient places to put solar.

He’s not wrong. For one thing, panels best capture photons when they are at a slight angle (say, 30 degrees to the ground) rather than parallel or perpendicular to the sky. And with an auto ecosystem increasingly wired for electrons — including charging infrastructure — on-car solar systems don’t have to do all the heavy lifting. Any EV can be “solar-powered” by plugging into an array of panels at home or a charger that is itself powered by solar energy.

“The vehicle is not the place in which these two technologies could interact in the most substantial way,” says Jessika Trancik, the engineering professor behind MIT’s CarbonCounter. But Trancik concedes that there’s a psychological value to having a trickle of charge anytime it’s light out, especially for luxury customers — in a suburb full of sunroofs, a solar roof would be a big flex. She says we may also “reach a point where it makes more economic sense for a wide range of vehicles to have some solar installed.”

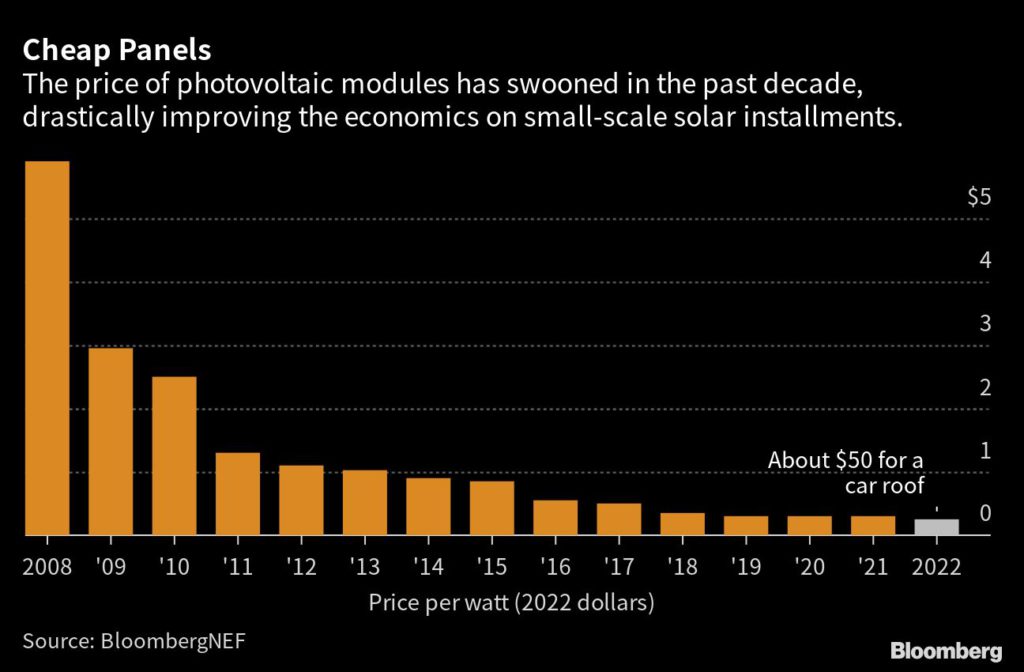

To be sure, the cost-benefit analysis on small-scale solar installments has steadily improved as photovoltaic hardware becomes both cheaper and more efficient. Over the past decade, the price of solar modules per watt of power produced plunged by 78% to roughly .24 cents per watt, according to BloombergNEF. At that rate, a panel array the size of the one on the Sonata has dropped from $222 to about $48. BloombergNEF expects the glut of cheap product to continue this year as another nine panel-makers hit the market, a 50% increase over the current crop.

Still, the use case for a truly solar car remains limited, essentially to driving on extremely remote routes — far from buildings and EV chargers — and for extremely small distances. Mars, for instance, is the perfect use case; the weekly trek to soccer practice, not so much.

But the impracticalities aren’t stopping companies from continuing to try; after all, the sun is hard to ignore and it never stops showing up. The next American Solar Challenge takes place in June, and Aptera is one of several startups still working to get a sun-powered passenger car over the financing finish line.

Instead of trying to maximize the size of the car’s solar array, Aptera set out to minimize the car itself. Its vehicle, dubbed the Gamma, approximates a silicon-skinned tadpole; even the doors scissor open like gills. The Gamma is 36% lighter than a Toyota Prius, 38% more aerodynamic than a Tesla Model S and cuts down on rolling resistance by using three wheels instead of four. As a result, Aptera’s whip can squeeze about 40 miles out of a day’s sun, slightly more than the 31 miles a day covered by the average US driver.

“It’s really just a math equation,” says Chris Anthony, Aptera’s co-founder and chief executive officer. “Turns out, we could come up with a really compelling formula and solution.”

When Anthony started cobbling the Gamma together about a decade ago, solar panels were half as efficient as they are today, and electric motors and lithium-ion batteries were prohibitively expensive. Today, Aptera is free-riding on the billions of R&D dollars that the auto industry sunk into electrification in recent years.

Still, the sun is slow-charging at best. Topping up the Aptera rig solely from its roof array takes about a week, though the Gamma can also be plugged in. And Aptera is nowhere near road-ready, at least not at scale. The company is currently pitching its prototype to investors, hoping to land a check big enough to produce the vehicle en masse.

Meanwhile, most Americans don’t want to sacrifice size and comfort for sustainability on the road; they want “rolling houses,” Anthony says. But Aptera doesn’t need most Americans to buy its vehicle; it just needs a few, and the 42,000 who have already ordered one are a start. As the market for solar-powered driving continues to evolve, one thing that hasn’t changed is Anthony’s sales pitch: “You get all the fuel from the giant nuclear power plant in the sky.”

(By Kyle Stock)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments