How Europe’s battery hope has become a symbol of the EV bust

Northvolt AB was supposed to power Europe’s response to the likes of Tesla Inc. and China’s fast-growing electric vehicle makers. Instead, the Swedish battery company is fighting to stay afloat.

As it faces a crushing liquidity crunch, the company’s creditors will meet Friday to decide on freeing up funds critical to its survival. On Thursday, Harald Mix, Northvolt’s founder and owner of a 7.2% stake, said he plans to provide new capital to the company, pointing to the “important role” it plays in European competitiveness.

Burning cash as it struggles to deliver the batteries it promised customers, Northvolt this week said it’s shedding a fifth of its global staff and suspending the expansion of its main factory in northern Sweden. With Europe’s battery boom turning to bust, more pain may be in the offing.

“There will not be big enough demand to meet supply and Northvolt may very well be the first casualty of the market correction currently underway,” said Fredrik Erixon, director at the Brussels-based European Centre for International Political Economy.

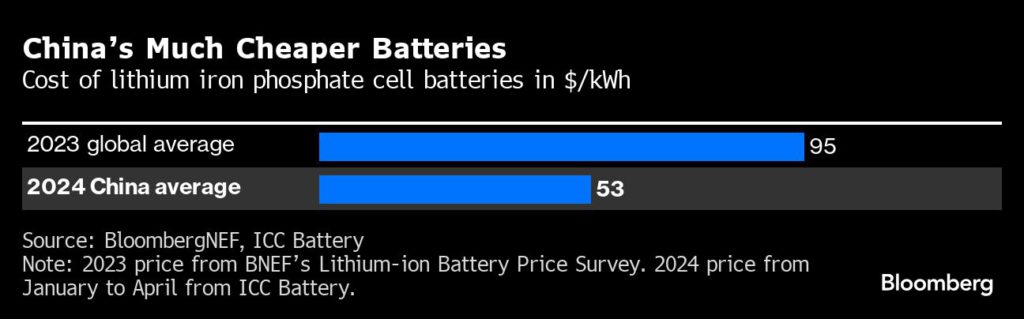

At stake is Europe’s effort to build a critical industry in a global marketplace dominated by Chinese rivals like Contemporary Amperex Technology Co and BYD Co. that are selling batteries and EVs at unbeatable prices. Northvolt’s woes also throw into question Europe’s ambitious push to build a self-reliant green economy.

It’s a stunning reversal for a company that was less than a year ago wooing investors with a planned initial public offering that would have valued it at $20 billion. It was the first recipient of the European Union’s green aid aimed at stopping businesses from being lured away by incentives offered under US President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, and was promising large-scale factories across Europe and North America.

But like some others in the industry — Rivian Automotive Inc., for instance — Northvolt tried to do too much too quickly, and by its own reckoning had teams that were not always qualified for operating at scale. It struggled to provide customers like BMW AG with the battery cells they needed and at one point couldn’t meet the deadlines of others like Scania CV AB.

Northvolt’s funding was backed by orders worth more than $55 billion from companies including Volkswagen AG and BMW. But the production woes and flagging EV demand starved the company of much-needed revenue, leaving it with cascading financial troubles.

Salaries and social security contributions for staff were more than three times higher than revenue from customer contracts last year. The company finds itself short of cash less than a year after securing a $5 billion green loan facility that brought its total debt and equity commitments to more than $13 billion.

Northvolt has hired consulting firm Teneo for restructuring advice, including contingency planning should it fail to win revised terms from lenders. That said, the company has made significant progress in financing talks over the past couple of weeks, a spokesman said in an email, declining to provide specifics.

Trouble has been brewing at the company for some time now. By May, its IPO plans had been shelved. In July, it said its operating loss more than tripled to $1.03 billion last year, with revenue advancing slightly to $128 million. It also said it was having to push back the ramp-up timelines at its four major sites. In August, it said it was closing a Californian research arm, and this month, struggling to conserve cash, it mothballed a cathode active material production facility and terminated another, both in Sweden.

“The industry is under multiple layers of pressure spanning across slower global demand, falling prices and an R&D race to next-generation technologies,” said Joanna Chen, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst in Hong Kong. “Competition is getting tougher in Europe with Chinese battery makers like CATL scaling up their local factories.”

Conceived by two former Tesla executives in 2016 — when money was practically free and inflation a distant memory from a bygone era — Northvolt moved ahead quickly in its early years. By 2019, the company, which counts Volkswagen and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s asset management arm among investors, had three factories under development. Its first lithium-ion battery cell was assembled in December 2021.

Northvolt’s stated aim has been global capacity of 230 gigawatt-hours by 2030 across its factories, or enough batteries to power about 3.8 million vehicles. Currently, its only running site Ett, near the Swedish city of Skelleftea, has a 16 gigawatt-hour capacity, according to BloombergNEF.

In addition to that site, Northvolt said this month it “remains committed” to its NOVO joint venture with Volvo Car AB in Sweden, Northvolt Drei in Germany and Northvolt Six in Canada. It plans to communicate timelines and potential cost savings at those locations this fall.

“It’s all about scale,” then-chairman Jim Hagemann Snabe said in early 2023, underscoring the breadth of its push into the new technology.

But scale is something the company has had trouble with.

It has been stymied by severe quality problems — like a high number of faulty cells that can’t be used — and an inability to quickly ramp up mass production, both of which have raised its costs and restricted revenue. A €2 billion order was canceled by BMW in June — citing quality issues. Volkswagen’s truckmaking arm Scania once complained about slow deliveries.

Still, Volkswagen said it remains a supporter of Northvolt’s ramp-up. BMW, too, is keeping the door open to include Northvolt at some point as a next-generation cell supplier, but that’s contingent on the company showing it can produce those Gen6 round cells to the carmaker’s specifications and at scale, according to people familiar with those discussions.

“Trying to simultaneously scale manufacture across multiple value chain segments is hard,” said Antoine Vagneur-Jones, head of trade and supply chains, energy transitions at BloombergNEF.

Early on, Northvolt co-founder Peter Carlsson had singled out access to competence as a bottle-neck, saying in 2021 that “it’s incredibly hard to get a hold of great cell designers and people with extensive experience in building these kinds of factories.”

As the company works through its woes, the Swedish government has made clear it won’t be bailing it out and Germany says it’s in “constant contact” with Northvolt. Analysts like BloombergNEF’s Vagneur-Jones say the EU may be forced to act, and may even be “investigating the possibility of tariffs on batteries.”

But for some observers, it’s a losing battle.

“This is a market that will undergo seismic changes in the coming 20 years, and I don’t see European companies leading the charge,” said Erixon.

(By Kati Pohjanpalo, Charles Daly and Jonas Ekblom)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments