Wild markets gatecrash London Metal Exchange Week party

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

This year’s London Metal Exchange (LME) Week was a subdued affair by comparison with past excess.

Put on ice last year due to covid-19, the annual metals party returned in slimmed-down form with many opting for virtual over physical drinks.

Analysts were in equally sober mood.

Everyone’s still positive on the longer-term energy transition story but more immediately worried about China.

The debt problem faced by real estate developer China Evergrande Group is no Lehman Moment, to quote Bank of China’s head of commodity strategy Amelia Fu, speaking at the LME Seminar. But weakening Chinese property sales spell trouble for what is a big metallic demand driver.

Average copper, nickel and zinc prices will decline next year as slowing demand growth coincides with increased supply, according to research house CRU, summing up the broad consensus among analysts last week.

Unfortunately, no one told the markets, which rudely gate-crashed last week’s proceedings.

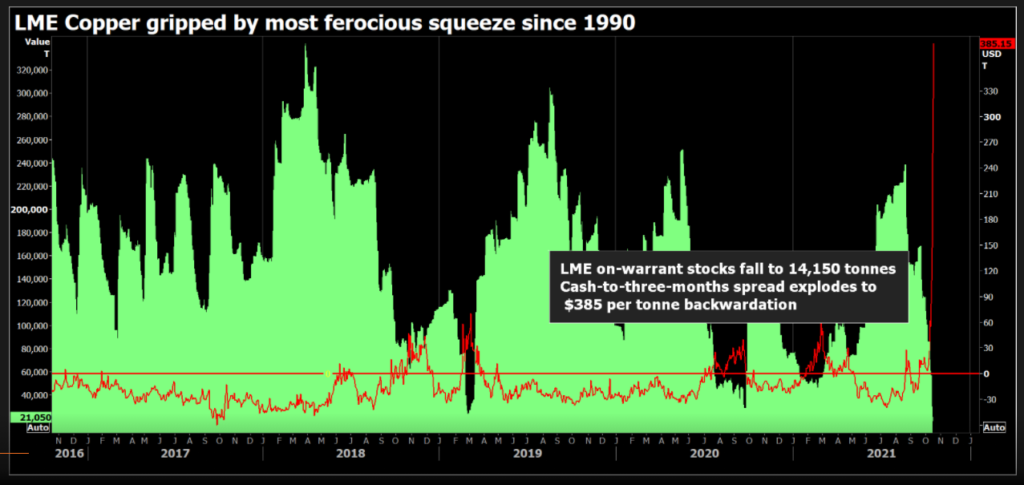

By Friday’s close zinc had shot up to a 14-year high of $3,944 per tonne and copper was in the grip of the most ferocious squeeze seen in the London market since 1990.

Related read: Copper price soars to new high as stockpiles hit 47-year low

Power woes galvanise zinc

Jonathan Leng, principle zinc analyst at WoodMackenzie, had the unenviable task of explaining why the research house is expecting prices to weaken to $2,900 per tonne next year just as Nyrstar announced Wednesday it was cutting output by up to 50% at its three European smelters due to the soaring price of electricity.

The zinc market was caught equally off-guard by the potential metal loss at what amounts to 700,000 tonnes per year of collective annual capacity.

China’s power woes were in the price. Europe’s weren’t and the sense of panic was reinforced when Glencore said it too “is monitoring the situation across its European zinc smelters and adjusting production to reduce exposure to peak price periods during the day.”

LME three-month zinc opened last week at $3,160 and closed it out at $3,795 after visiting that 14-year high on Friday. Time-spreads were similarly rocked, the cash-to-three-month period flipping from small contango to a backwardation of $52 per tonne at the Friday close.

Copper carnage

That level of tightness, however, pales into insignificance next to the London copper market.

The LME copper cash-to-threes period exploded to a $350-per tonne backwardation on Friday with the cash premium rising further to $380 on Monday morning. That’s the widest spread since 1990, when the cash premium reached $483.

The cost of rolling a position overnight reached $175 per tonne at one stage on Friday and was still painfully high at up to $100 on Monday morning.

This squeeze came with advanced warning in the form of the daily 10,000-tonne cancellations of LME stock that have been running since the start of the month.

The pace was upped in the Friday LME stocks report, which showed another 33,000 tonnes had been moved into the physical departure lounge. That left just 14,150 tonnes of available copper in the LME’s warehouse system, the lowest level since March 1974 and enough metal to cover global consumption for just five hours.

Is all this cancelled copper going to China, where stocks are also low? Or is it part of a premeditated attack on unwary bears?

The truth is it doesn’t matter much for anyone still short of cash-date copper or the cluster of call options sitting above $3,000 per tonne, which were all brought into play on last week’s price action.

“Copper remains a physical good, whose futures price is ultimately tied to the ability to deliver physical units into the exchange,” according to Goldman Sachs, which highlighted the depletion of LME stocks in its counter-consensus bullish call for the copper price to hit $10,500 by year end.

LME three-month metal has almost got there with a Monday high of $10,452.50. Cash metal has already punched higher.

Monday’s LME stocks report showed 5,150 tonnes of arrivals and short-position holders can only hope more is on the way. A lot more.

Structural shifts in aluminum and nickel

Aluminum was the analysts’ bull pick last week and the LME three-month price has duly obliged by racing up to a 13-year high of $3,229 per tonne on Monday.

Here too, though, events are unfolding faster than the consensus as China’s power crisis spreads to Europe with several regional smelters thought to be lowering production in the face of spiralling spot power costs.

A new concern is a growing shortage of both silicon and magnesium due to supply-chain disruption. The two metals are widely used across a spectrum of aluminum products, suggesting a downstream hit may shortly be following the upstream smelter hit.

The underlying narrative, however, remains one of a structural shift in the aluminum market as China tries to pivot away from coal in its power mix, leaving a big question mark hanging over its coal-hungry aluminum smelting sector.

Nickel is also facing a “structural uplift in pricing” thanks to rising usage in electric vehicle batteries, according to Jessica Fung, head strategist at Pala Investments.

One-third of nickel will be used as an energy source by 2030, creating an entirely new market and price driver for the metal, Fung told the LME Seminar.

Whether there will be too little or too much supply by that stage remains a hot topic among analysts and in a week of broken records, LME nickel didn’t do much at all.

Tin the wild child

There is no doubt that tin remains in short supply.

Few bank analysts even cover the tiny tin market but it has been the wildest of all this year and remains so, LME three-month metal extending its bull charge to another all-time high of $38,249 per tonne on Monday.

The cash-to-three-month tin spread closed on Friday at a $1,250 per tonne backwardation, which would have been extraordinary in any year but this after it hit $6,500 in February.

Tin is trading at scarcity levels and is likely to continue to do so for another three to six months, according to Tom Mulqueen, head of research at LME broker AMT.

Super low inventory – LME warranted stocks are just 255 tonnes – has limited the market’s ability to absorb supply shocks, Mulqueen told the LME Seminar.

This is a problem when there are so many potential supply shocks, ranging from renewed outbreaks of the coronavirus to power shortages in both China and Europe and a dysfunctional global shipping sector.

LME Week can often be a wild occasion for the great and the good of global metals trading. This year it was the markets that turned wild. And as tin has shown, they can remain wild for a long time before any sort of normality returns.

(Editing by Susan Fenton)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments