Home: Volkswagen powers up for the EV revolution

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess is no Elon Musk but the German carmaker is following a path already traveled by Tesla as it gears up for the mass rollout of electric vehicles (EV).

Even last week’s “Power Day”, a two-hour streaming event at which Diess explained the company’s EV strategy, seemed a conscious nod to Tesla’s “Battery Day” last September.

Like Tesla, Volkswagen has decided to take control of its own battery destiny by constructing six European gigafactories with collective annual capacity of 240 gigawatt hours (GWh) over the next decade. The announcement sent its shares into a Tesla-style frenzy.

Batteries are, quite literally, the driver of the e-mobility revolution and Volkswagen has clear ideas about what it wants and at what price as it prepares to transition from the internal combustion engine (ICE).

Its roadmap has major implications for battery metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

Driving down the price

Core to Volkswagen’s EV strategy is the need to bring EV prices down to parity with conventional ICE vehicles and to accelerate charging times.

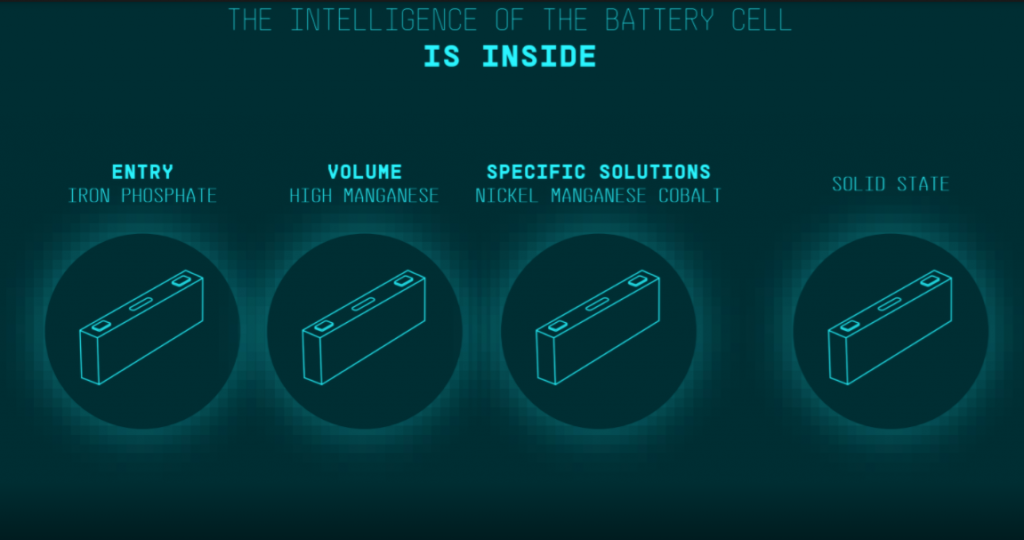

Part of this challenge will be met by using a unified prismatic cell across 80% of the group’s models. The balance 20%, designated “specific solutions”, will use bespoke battery design for high-end brands such as Audi and Porsche, where performance not price counts.

Even more significant in driving down costs will be the battery chemistries deployed within that standardised cell.

Volkswagen’s vision is to “take control of its own battery supply”

Volkswagen wants to cut by half the price of a low-end “entry-level” car and to do so it will use lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) cathodes.

A couple of years ago this relatively dated battery chemistry seemed set to be superseded by more energy-efficient combinations but significant technical improvements have seen a resurgence in LFP usage, led again by Tesla, which has been installing it in its Chinese Model 3 sedans.

Volkswagen will do the same for the same reason.

LFP batteries don’t use scarce and high-priced nickel or cobalt but rather plentiful and cheap iron and phosphate. With raw materials now accounting for the largest part of a battery’s cost, switching metallic cathode inputs is the single most powerful cost lever.

In the battery mix

And one that Volkswagen also intends to pull for its mass-market, mid-level range of vehicles with an ambition to move to high-manganese (HM) batteries.

This would represent a significant shift from the nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) chemistry that has become the cathode of choice for any EV that needs a bit more performance oomph.

But high-manganese batteries also use no cobalt and a lot less nickel and a chemistry such as lithium-nickel-manganese-oxide (LNMO) reduces by 47% the cathode costs per kilowatt-hour relative to NCM batteries with high nickel ratios, according to analysts at Roskill. (“VW Power Day”, March 2021).

“High-manganese cathodes are considered one of the strongest candidates for the next generation of lithium-ion batteries because of their cost advantage, cobalt-free nature, and strong electrochemical performance,” Roskill says.

But they’re not commercially viable yet. Nor are the solid-state lithium batteries with a 12-minute charging time Volkswagen is targeting as its chemical end-game through its investment in QuantumScape.

In the interim, some form of NCM will be used, as it will be for the higher-end marques with prestige pricing levels.

But the direction of travel is clear. Volkswagen wants to de-risk its battery inputs by minimising usage of cobalt and nickel.

Both are high-priced, volatile markets with supply-chain problems, a dependence on the Democratic Republic of Congo in the case of cobalt and too little battery-grade material in the case of nickel.

Roskill estimates Volkswagen’s group usage of nickel and cobalt surged by 1,198% and 816% to 7,047 tonnes and 1,868 tonnes respectively between 2018 and 2020.

Extrapolate that usage growth forwards as Volkswagen powers up its EV offering and you can start to see why the company is setting its store on a high-manganese battery solution.

However, the overriding message is that no single battery technology is going to dominate the EV space. Volkswagen, like Tesla, is going to deploy different chemistries for different vehicles depending on price.

Taking control?

Volkswagen’s vision is to “take control of its own battery supply”, according to Simon Moores, managing director of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, speaking on the company’s streamed analysis of the automotive giant’s EV plans.

Volkswagen’s ambitious plan to build six European gigafactories by 2030 sets the company up to be a major battery player in its own right, the incumbent auto giant becoming battery disruptor.

For now, Volkswagen’s massive investment in EVs – 35 billion euros ($41.7 billion) by 2025 – is centred on cell technology and further downstream in the form of charging infrastructure and recycling of spent batteries.

The company, notes Roskill, is “parking its capital in segments closest to its current manufacturing business model and where it feels it can contribute the most value.”

Tesla has passed this stage and is moving further upstream, extending its reach into cathode raw materials sectors.

The company is poised to get involved in lithium hydroxide production based on an ore supply deal with Australian miner Piedmont Lithium.

It has a “technical and industrial partnership” with the new owners of Vale’s New Caledonian nickel operations.

Elon Musk has reached the conclusion that battery capacity does not ensure supply-chain security if raw material markets are heading into periods of supply scarcity.

Volkswagen didn’t say much at all about its upstream metals requirements, particularly lithium, which is core to whatever battery chemistry is deployed.

The lithium supply chain is audibly creaking at the moment as producers switch from cost-cutting to expansion mode, a collective turnaround not helped by notoriously long lead times in commissioning processing plants to battery-quality standards.

Battery makers, and of course Tesla, have already been carving out future supply deals with lithium producers. An already competitive market landscape looks a lot more congested with Volkswagen powering up battery capacity.

At the moment Volkswagen seems to be placing its faith in the potential for partnership with raw materials producers. Tesla has decided faith is not enough.

There’s a strong prospect, as Benchmark Minerals’ Moores pointed out, that carmakers’ battery and power days will be followed by metals and minerals days.

(Editing by Jason Neely)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments