Home: Power is a double-edged sword for global metals sector

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The world will need a lot more metals such as copper, nickel and aluminum if it is going to decarbonise.

The potential “green” demand boom from more renewable energy, more power infrastructure and more electric vehicles is tomorrow’s promise for such “energy transition” metals.

Yet, as first China and now Europe is discovering, power is a double-edged sword for metals producers and manufacturers.

A power crunch in China has idled over two million tonnes of the country’s aluminum production capacity.

The unfolding energy crisis in Europe has halted the Plovdiv zinc-lead smelter in Bulgaria and forced others such as Nyrstar’s zinc smelter in the Netherlands to reduce output during peak power periods.

In China the power constraints are moving down the supply chain to impact not just primary producers but also products manufacturers, an ominous sign of what may be in store for Europe as winter looms.

Chinese and European energy crunches result from a complex mix of drivers.

All add up to the same metals-power paradox. How to produce more metals to decarbonise the world’s power systems when decarbonisation adds to the strain on existing power availability?

On the front line

European power prices have surged because of reduced Russian gas supply, lower wind generation, nuclear maintenance, rising carbon prices and rebounding post-pandemic demand.

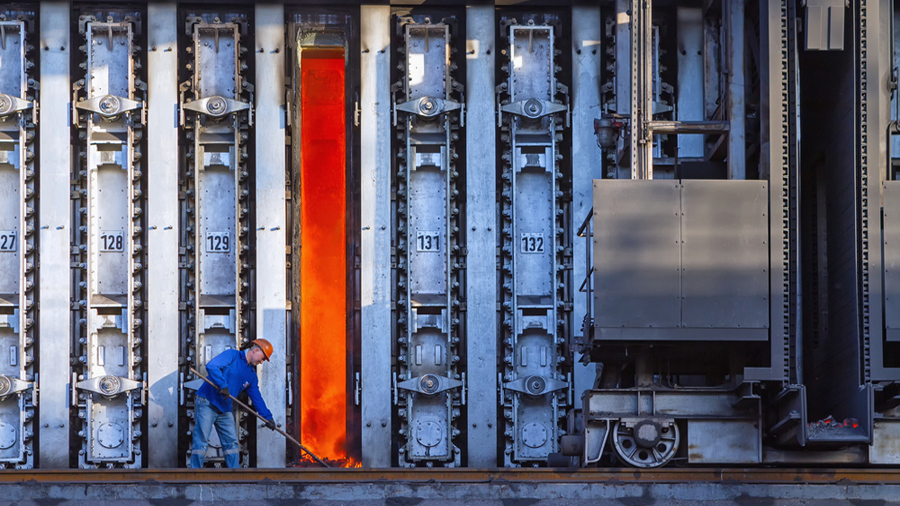

Large metal production plants are highly exposed to electricity price spikes because they are intense users of power to convert raw materials into refined metal.

China’s power crunch is rapidly evolving from bull to bear influence on metals pricing

“Producers of aluminum, copper, nickel, zinc, and silicon are right at the frontline of those industries impacted by Europe’s high electricity prices,” according to non-ferrous metals industry association Eurometaux, which is urging the European Commission to take action.

The impact varies by country, since the European power market is far from homogenous.

Bulgarian industrial users, for example, complain that local power tariffs are more than double the levels applying to immediate competitor countries.

But any industrial plant exposed to the spot European power market is probably struggling.

Aluminum smelters are particularly exposed because they need huge amounts of power for the electrolytic process of converting alumina into metal.

Eurometaux estimates an aluminum producer consuming 14.5 MWh per tonne of aluminum produced has seen its energy costs almost quadruple this year from 580 to over 2,000 euros per tonne, accounting for more than 80% of the current London Metal Exchange (LME) price.

China’s aluminum sector has found itself on the front line of that country’s energy crunch for precisely the same reason. Smelters are easy targets for local governments looking to alleviate stresses on the power grid.

Until now this has been a bullish narrative for markets such as aluminum, which has hit its highest levels in a decade on falling output in the world’s largest producer.

Moving downstream

But in China power shortages are moving downstream, a decidedly bearish development.

China’s tin sector is a case in point.

Producers in Yunnan and Guangxi provinces were forced to curtail output in May and August respectively by power rationing but seem so far to have dodged the latest restrictions.

Not so their customers, however.

Power rationing in southern provinces such as Guangdong and Jiangsu is idling significant amounts of soldering and tin-chemical capacity, according to the International Tin Association.

The demand hit has stopped the Shanghai tin rally in its tracks, the most active contract sliding by 4.5% at one stage on Tuesday.

Such disruption is spreading with many aluminum consumers across the south of China now operating just two days a week, according to LME broker Marex Spectron.

Indeed, power constraints are impacting ever more parts of China’s huge manufacturing economy, with Goldman Sachs estimating that as much as 44% of national industrial activity has been affected.

The bank has just cut its Chinese growth forecast for this year from 8.2% to 7.8% due to the “significant downside pressures” on industrial production.

The pressure on commercial power users is only likely to become more acute as policy-makers prioritise household heating going into the winter months. That is not good news for metal markets, given that China remains such a significant driver of global demand. China’s power crunch is rapidly evolving from bull to bear influence on metals pricing.

Structural challenges

China’s power woes are in part caused by one-offs such as the rise in the price of coal, the largest component of the country’s power mix, and drought in hydro-rich Yunnan province.

Related Article: Visualizing China’s evolving energy mix

But in part they are down to Beijing’s decarbonisation policies, expressed in the form of quarterly energy usage and efficiency targets for each province.

Those provinces that miss their targets must reduce power generation in the next quarter, which translates into mandatory rationing across energy-intensive sectors such as metals.

Where China is today, the rest of the world may follow.

Europe’s pivot away from fossil fuels leaves it more vulnerable to the sort of “perfect storm” conditions that are driving the current electricity price surge.

The danger is that industrial metals and other power-intensive sectors are constrained by higher power prices just as they are attempting to reduce their own carbon footprint.

“If electricity remains too expensive, it will disincentivise industrial electrification as a decarbonisation route,” warns Eurometaux.

Sustained high prices could lead to operators choosing to relocate outside the eurozone area, undermining the bloc’s drive for greater self-sufficiency in raw materials, it added.

And without sufficient metallic raw materials the EU’s whole “Green Deal” is at risk.

The causes of China’s and Europe’s power crunches are different, reflecting the unique features of each electricity system.

Coal is China’s big headache, both in terms of immediate supply and in trying to transition its grid away from using the stuff.

Europe is further down the energy decarbonisation path but at the expense of needing more imported gas when wind and sun fail to blow and shine.

But the common troubling theme is the same. How to produce more metals to go green when the price of going green constrains metals production?

(Editing by Barbara Lewis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments