Here’s who wins and who loses from the surge in commodity prices

The world’s recovery from the coronavirus pandemic has sent prices for energy, metals and food soaring, helping big commodity exporters while hammering those nations that buy the bulk of their raw materials from others.

Commodities as a whole have risen more than 20% this year, and around 50% in the case of crude oil. The Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index is at a decade high and heading for its fourth-straight monthly increase. Big Oil companies and miners, awash with cash, are returning billions of dollars to shareholders through dividends and buybacks.

Few analysts expect the gains to reverse soon and many think they’ve got further to run.

Oil and gas producers in the Arabian Gulf are set to be the biggest winners this year economically

For the likes of Russia and Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest energy exporters, it heralds good times. For others, it puts huge strain on their balance of payments and currencies, leading to higher inflation.

Here’s a look at which countries are benefiting and which are the most vulnerable.

Winners and losers

Oil and gas producers in the Arabian Gulf are set to be the biggest winners this year economically, according to a Bloomberg Economics survey of almost 45 nations. The United Arab Emirates and Qatar will each see their net exports increase by more than 10% of gross domestic product compared with 2020, while Saudi Arabia won’t be far behind.

Japan and most of Western Europe will take a hit as they’re forced to spend more commodity imports. The five biggest losers will be in Asia, with the likes of Vietnam and Bangladesh suffering from dearer fuel and food.

$550 billion transfer

The gains for commodity exporters will easily outweigh their losses last year as the pandemic spread and crushed demand for raw materials. Bloomberg Economics estimates that $550 billion will shift from importers to exporters in 2021, nearly double the $280 billion reverse transfer last year when prices collapsed.

In absolute terms, Russia will benefit the most, with its net exports rising almost $120 billion in 2021. Australia, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and the UAE follow, each with gains of more than $50 billion. China’s net exports will drop by around $218 billion. That’s far higher than the figures of around $55 billion for the next-worst off countries, India and Japan.

US vs China

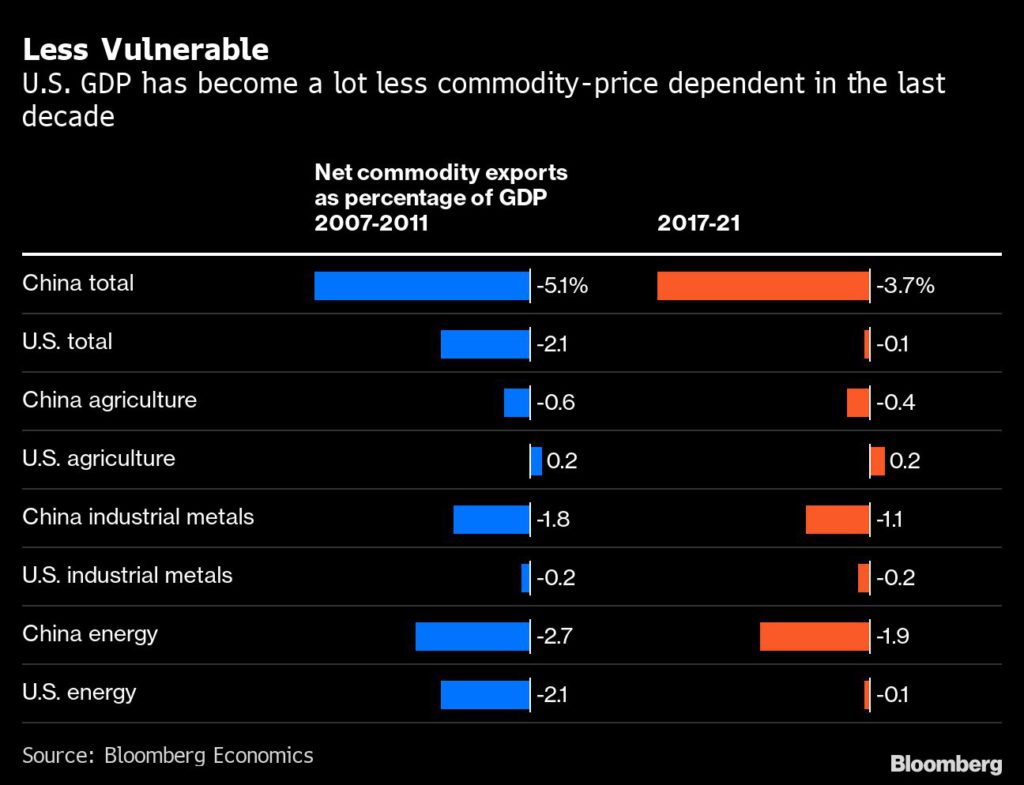

The U.S.’s net exports will fall too, but only by $22 billion, a tiny amount relative to its $21 trillion of annual economic output. The country has almost wiped out its exposure to imported commodities in the past decade, thanks largely to the huge increase in its shale oil and gas production.

China has also become less vulnerable. But the improvement’s been much smaller, especially when it comes to energy.

Middle East food woes

Food prices have risen for all bar one of the past 13 months and stand near the highest level since 2011, according to United Nations data. That’s especially a problem for the Middle East, where higher costs for everything from bread to meat helped trigger the Arab Spring protests 10 years ago. Seven of the 10 weakest links today are in the region, according to a Bloomberg Economics analysis of emerging markets. They include Yemen, wracked by civil war, as well as Sudan, Tunisia and Algeria, all of which have recently seen large protests over falling living standards.

“The commodity boom is shifting about $550 billion to big natural-resource producers like Russia, Saudi Arabia and Australia from large importers such as China, India and Europe. But relative to the size of the economy, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Thailand will face the highest costs.”

Ziad Daoud, Chief Emerging Markets Economist

(By Paul Wallace and Zoe Schneeweiss, with assistance from economists Ziad Daoud and Felipe Hernandez)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments