Heat waves across Europe show dangers of weakening climate goals

Southern France was slammed by a heat wave so intense in June that Celine Imart was forced to harvest rapeseed in the middle of the night to avoid searing hot tractors from sparking fires in her fields. Farmers elsewhere had reported crackling dry crops spontaneously catching fire after coming into contact with the heat from harvesters.

Record-high temperatures had brought the earliest-ever heat wave across large sections of France, as well as to Spain and parts of Italy. For Imart, a 39-year-old sixth-generation farmer near Toulouse, the dry weather so early in the year meant the harvest of durum-wheat, the variety used to make pasta, was finished two weeks earlier than usual and yielded 30% below normal.

“From one day to another, it passed from too much rain to too dry,” Imart said, adding that the phenomenon accelerated the development of crops. “We see it in our farm — the time of the harvest is earlier and earlier each year, advancing all the time.”

Now, Europe is bracing for a new heat wave, with temperatures in parts of France flirting with 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) this week and next. In London the thermometer may hit 35°C next week and may go even higher elsewhere in southern England. Seville, in the south of Spain, is expected to touch highs of about 45°C this week.

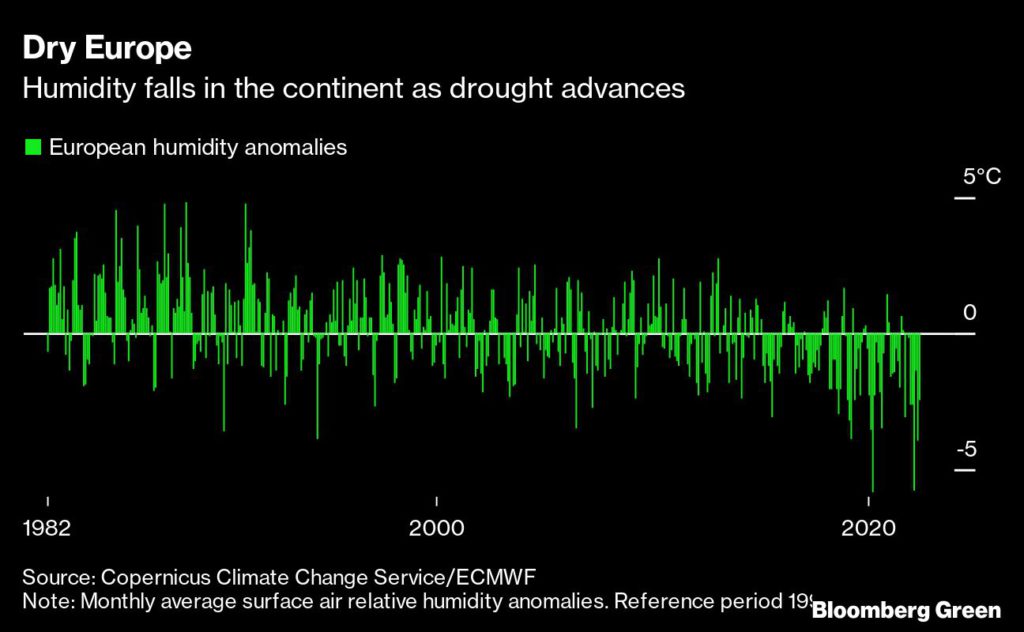

Waves of blistering heat and severe droughts are emerging as weather phenomena — made worse by global warming — that will overwhelm large swathes of Europe this summer. Spain and Portugal are suffering the driest conditions in more than a millennium; Italy’s longest river Po is at its lowest level in 70 years, while sections of the Rhine River, western Europe’s most important waterway, haven’t been this low at this time of year in at least 15 years. Crops are wilting and power plants are being forced to shut down, threatening an inflation-weary region with a further boost in food and energy prices.

As European governments facing reduced Russian gas supplies bolster energy stockpiles by burning more coal, planning new liquefied natural gas terminals and extending gas pipeline networks — effectively backpedaling on decarbonization — the extreme weather is a grim reminder of the dangers of delaying climate action. It shows that efforts to hang on to the status quo are not an option.

“We have followed a rationale in the fight against climate change which is that we will always find ways to keep going with business as usual and that the global economy doesn’t need to change,” said Olivia Lazard, a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe focusing on the geopolitics of climate. “Year 2022 is the year when this myth is debunked because we’re going to face so many compound shocks.”

Europe had begun to concretely address climate change. The continent with the most ambitious green agenda unveiled a plan in July last year to achieve its goal to cut planet-warming emissions by 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels. Under the Green Deal, the bloc earmarked at least 1 trillion euros ($1 trillion) over 10 years in sustainable investments, allocated a third of its budget for the next half-decade to green projects and asked members to lay out at least 37% of the more-than 700 billion-euro pandemic-recovery package on spending that supports climate goals.

But those ambitions relied on gas piped from Russia to keep economies humming along while waiting for investments in renewables, electric cars and green technologies to cut emissions from heavy industry. Russia’s war in Ukraine has thrown that project askew, sending Europe quickly to dirtier fuels. Germany is delaying the retirement of some coal- and oil-fired power plants; the Dutch are lifting a cap on power from coal; Austria is reviving a shuttered coal power station and France is preparing a coal plant as a reserve for the winter. Several countries are also investing in terminals to import LNG and pipelines to connect them to existing networks — infrastructure that will last decades.

That means Europe will likely have to put in place more stringent emissions restrictions later this decade to make its targets.

Meanwhile, it’s the extreme weather events engulfing large parts of the region that have the attention of governments, which are being forced into calamity mode.

“Emergency support and response alone are not enough,” says Maros Sefcovic, a vice-president of the EU commission, the bloc’s executive arm. “Climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction and disaster preparedness are paramount.”

Italy this month declared a state of emergency in five northern regions affected by one of the country’s worst droughts. Water levels for the Po river, the main source of irrigation for crops for those regions, are 80% lower than normal. Several months without rains and an earlier-than-usual halt in flows from melting snow in the western Alps have made large sections of the river bed visible — so much so that a German tank from World War II resurfaced recently.

The Italian farmers’ association Coldiretti says the first half of this year was the hottest on record, with 45% less rain than normal. The drought will mean the loss of at least a third of the seasonal harvest of key crops of rice, corn and forage, with estimated damages of as much as 3 billion euros, it said.

Many Italian towns, including Verona in the north, have ordered citizens not to use water for non-domestic purposes during the day — for their gardens, for instance. In the Dolomites mountain range in northeastern Italy record high temperatures this month sent a glacial ice shelf crashing from the top of the Marmolada mountain, killing 11 people.

“This is a drama that was unpredictable but is for sure linked to climate change,” Prime Minister Mario Draghi noted, speaking from the nearby city of Canazei.

The Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Europe — comprising Spain and Portugal — is suffering the driest conditions of the last 1,200 years, according to a study in Nature Geoscience. The drought is caused by the expansion of a persistent high pressure system over the Atlantic, known as the Azores High, which blocks wet weather fronts. Higher carbon emissions have made such systems larger and more frequent, keeping rain away from the peninsula. The study’s authors expect it will continue to expand as greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere rise.

Signs of drought are visible everywhere in Spain, but specially along the Guadalquivir river basin, which flows through the southern region of Andalucia. The river is flowing at just 28% of its capacity. Water levels on reservoirs along the 660-kilometer (410 miles) river are so low that old human settlements are emerging. In Iznajar, Andalucia’s biggest reservoir, archaeologists found neolithic tools and ancient structures like grain mills dating from Roman times.

While water restrictions have not been ordered for the wider population, some towns have started to implement them anyway. In Aguadulce, near Sevilla, authorities have cut water supply at night. Further north, some towns have not filled public swimming pools, while others are seeing muddy water in taps. Cities like Madrid and Barcelona are creating networks of “climate refuges,” where people can cool off on hot days.

“What we are seeing are the impacts of ongoing climate change,” said Piero Lionello, a professor of atmospheric physics and oceanography at Universita del Salento in Italy. “Unless mitigation efforts are very successful in the next few decades, what we are observing now is a very small fraction of what will happen in the future.”

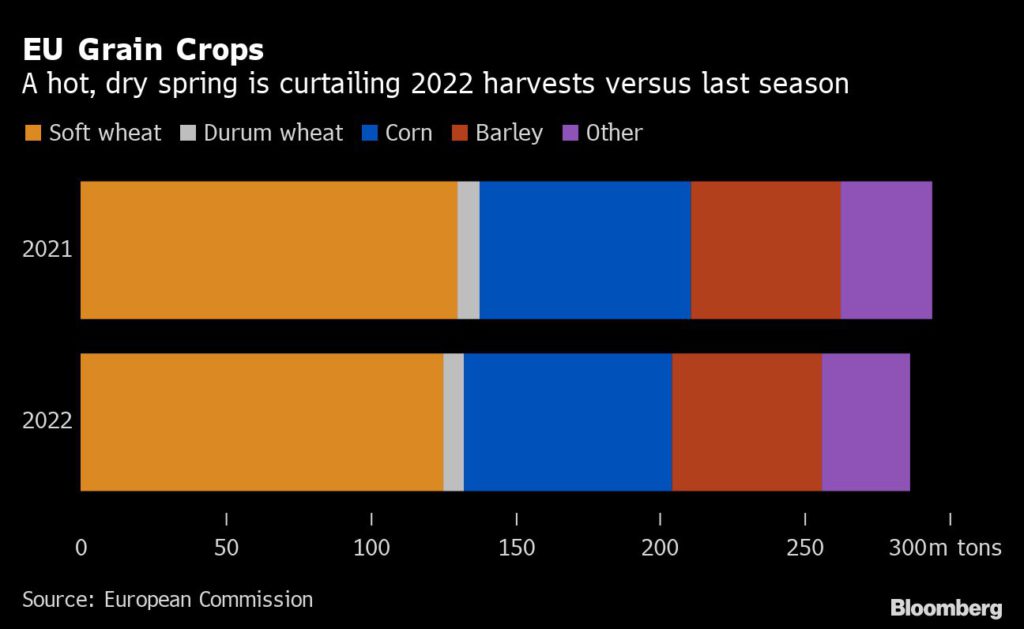

Already, food and energy security have been dented. The European Commission has slashed its 2022 soft-wheat crop estimate to 125 million tons, down 5 million tons from a prior estimate. Coming on top of Russia’s blockade of Black Sea exports from Ukraine — one of the world’s biggest exporters of wheat, corn and sunflower oil — the cuts in European production do little to alleviate the shortages that have sent food prices to record highs and raised fears of escalating global hunger.

The dry conditions are also disrupting power generation. In Italy, water levels at hydroelectric plant reservoirs have halved, leaving the country more reliant on dirtier natural gas. Even that source of energy isn’t protected from the drought. Already three gas plants in northern Italy have shut down because of low supplies of water from the Po river, needed to create steam that can spin turbines.

In France, hydropower output dropped 22% in the first half from a year earlier, data from power-transmission operator RTE shows. Power giant Electricite de France SA said it may have to reduce output at some of its nuclear plants during the summer as the lack of rain reduces the amount of river water available for cooling the reactors.

“Droughts are the most difficult climate event to adapt to because they accumulate over many months,” said Bob Ward, policy director at the London School of Economics’ Grantham Research Institute on Climate change. “We’re going to have to think about more radical solutions.”

Scientists say slashing greenhouse gas emissions is the only way to slow the pace of global warming. The window of opportunity to act before things become catastrophic is closing, according to a major report this year by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“We need to work better with nature, taking an agroecological approach to agriculture and increasing the use of trees into the landscape, which can provide lots of benefits for resilience to drought,” said Delphine Deryng, a lead author of the report. “It takes time, and in the short term it is quite challenging economically.”

And while drought is one of climate change’s most complex challenges, not all is lost, says Universita del Salento’s Lionello. Governments can put in place water-saving measures, build reservoirs, desalination plants, improve the efficiency of water usage and recycle it.

“The bad news is that water shortages will be an issue in the future, but the good news is that this is one of the sectors where adaptation can be more successful,” he said. “We now know much more than a century or than 30 years ago and we have lots of new technical capabilities, so if we get this right we have the potential for even improving living standards.”

(By Laura Millan Lombrana, Megan Durisin and John Ainger, with assistance from Alan Katz, Francois De Beaupuy, Will Mathis, Alonso Soto, Chiara Albanese, Josefine Fokuhl, Joao Lima and Marco Bertacche)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments