Shortages flagged for critical EV materials lithium and cobalt

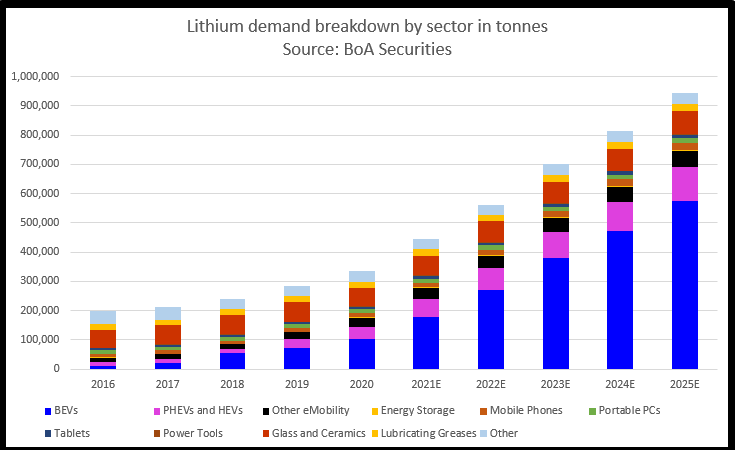

As the world moves to meet stringent targets for cutting carbon emissions — partly by phasing out internal-combustion engine cars — demand for lithium, cobalt and nickel vital for electric vehicle batteries will soar, raising the prospect of shortages.

High lithium prices have failed to spur investment in new capacity due to lower long-term contract prices, while the problem for cobalt supply is that it is mainly a byproduct of copper, meaning investment decisions are based on copper prices.

For nickel, new projects in Indonesia, which has the world’s largest reserves, mean the likelihood of major shortfalls may only come into play towards the end of this decade.

Lithium

Electric vehicle batteries can use lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide, but the industry typically talks of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) which contains both.

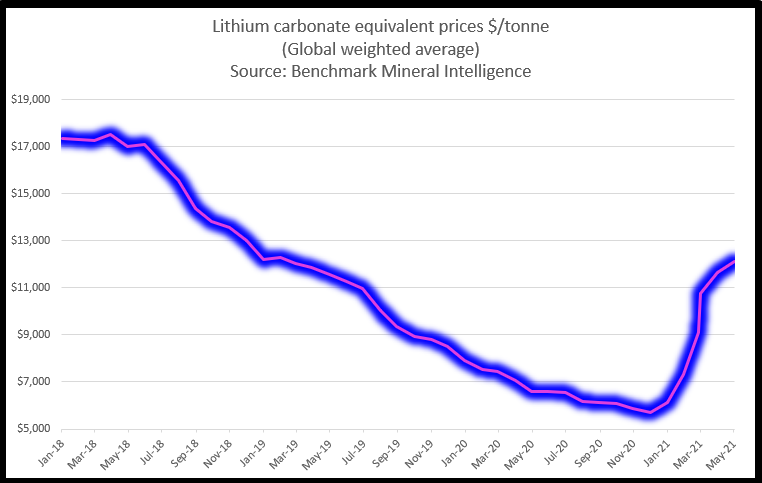

LCE prices on the spot market have risen above $12,000 a tonne, more than double the levels seen in November last year and the highest since January 2019, Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) says.

Those levels are high enough to incentivise investment in new capacity, but annual or longer term contracts signed in the last quarter of 2020 with lower prices are a barrier.

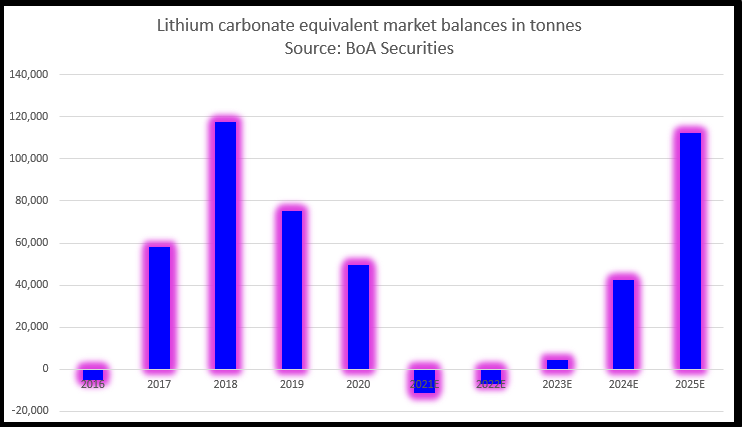

BMI’s George Miller forecasts a LCE deficit of 25,000 tonnes this year and expects to see acute deficits from 2022.

“Unless we see significant and imminent investment into large, commercially viable lithium deposits, these shortages will extend out to the end of the decade,” Miller said.

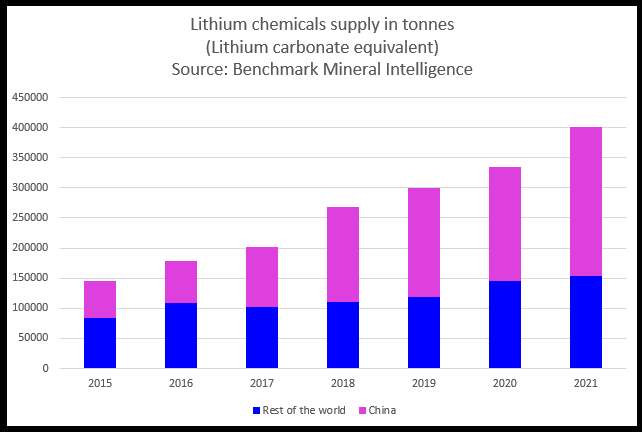

The location of more than 60% of processing capacity in China is a concern as it could pose a risk to electric vehicle supply chains in the United States and Europe.

Roskill’s analysts estimate lithium carbonate equivalent demand will rise above two million tonnes by 2030, a more than 4.5 fold increase from 2020.

Cobalt

Cobalt content in batteries has been cut significantly in recent years, but soaring sales of EVs mean demand for the minor metal is expected to rise overall, leaving deficits.

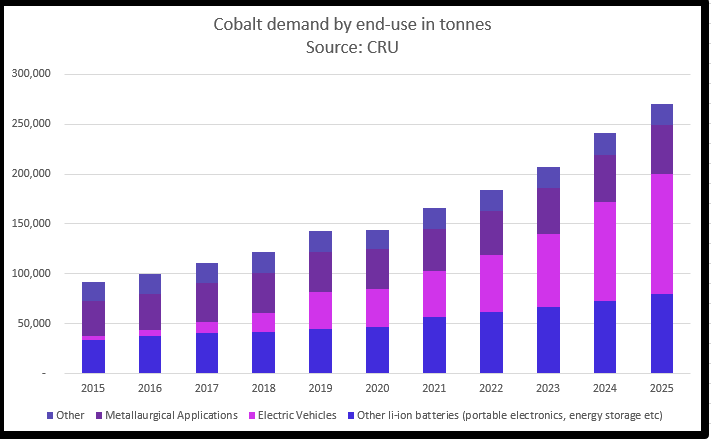

Analysts at Roskill forecast cobalt demand will rise to 270,000 tonnes by 2030 from 141,000 last year.

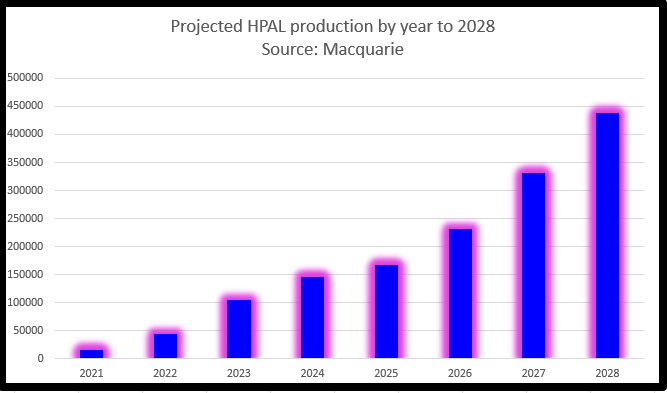

Indonesia’s high pressure acid leach (HPAL) projects will help cover some of the shortfall.

But the problem remains that cobalt is mostly a byproduct.

“It’s difficult to invest in cobalt specific capacity because it is a byproduct. There isn’t a mechanism within which supply can react to demand and prices,” said George Heppel, a consultant at CRU.

“If we look out to the mid-2020s, we could really do with another Katanga.”

Glencore expects its Katanga mine in Democratic Republic of Congo to produce 30,000 tonnes of cobalt this year.

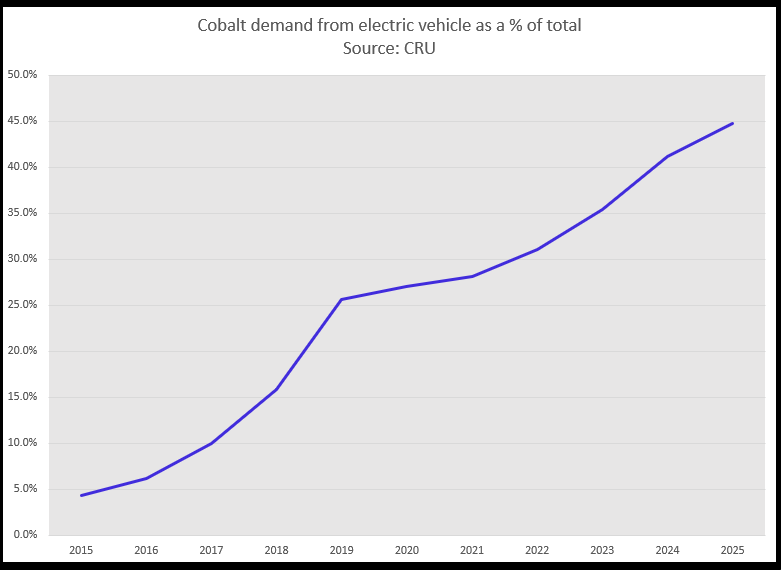

CRU forecasts cobalt demand from electric vehicles to account for more than 120,000 tonnes, or nearly 45% of the total, by 2025 compared with nearly 39,000 tonnes, or 27%, in 2020.

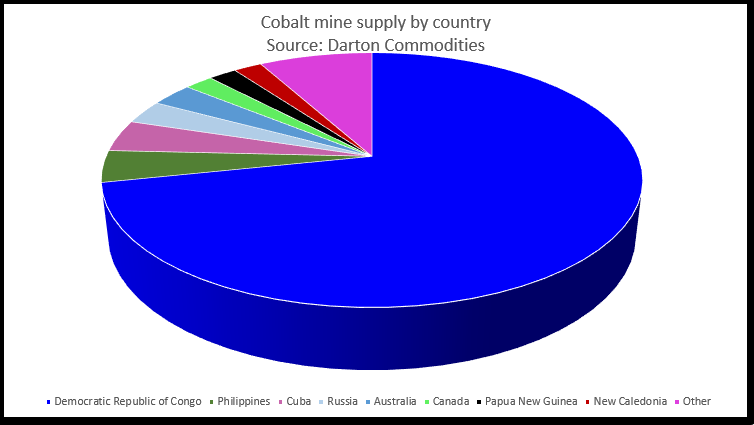

The world’s largest cobalt producer is the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is taking steps to develop controls and traceability of artisanal material to make it acceptable to those worried about human rights abuses.

Nickel

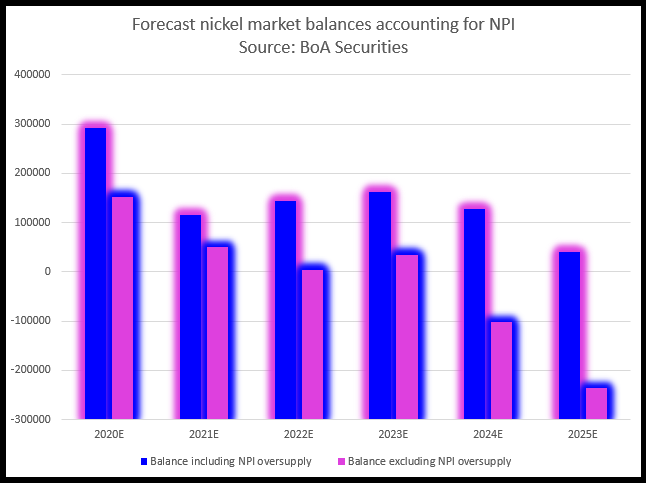

Concerns about nickel supply for battery chemicals dissipated after Chinese nickel pig iron (NPI) producer Tsingshan Holding Group said it would convert NPI into matte, which can be used to make chemicals for batteries.

“There are now projects totaling 300,000 tonnes per annum to convert NPI into a product that can be turned into sulphate for batteries,” Macquarie analyst Jim Lennon said.

“That nickel is on the verge of a surpercycle is hype. It will be over-supplied until at least the mid-2020s.”

Lennon also expects Indonesia’s high pressure acid leach (HPAL) projects to produce between 400,000-600,000 tonnes of nickel a year for much of this decade.

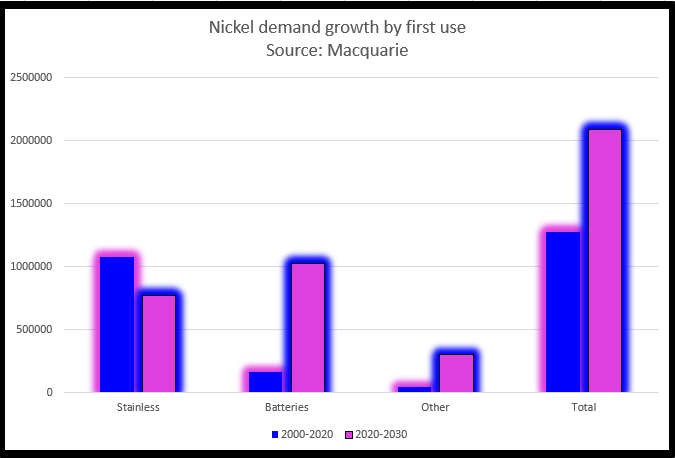

Global nickel supply is estimated at around 2.6 million tonnes this year. Of that about two-thirds will be used by stainless steel mills, most of them in China, while electric vehicles account for less than 10% of consumption.

Tsingshan said in March it would supply 100,000 tonnes of nickel matte to customers.

“There are other operators in Indonesia who could follow Tsingshan,” said BoA Securities analyst Michael Widmer, who expcts NPI supply to contribute to surpluses in 2024 and 2025.

(By Pratima Desai and Mai Nguyen; Editing by Veronica Brown and Barbara Lewis)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments