CHARTS: Energy transition metals poised for uneven, explosive run higher

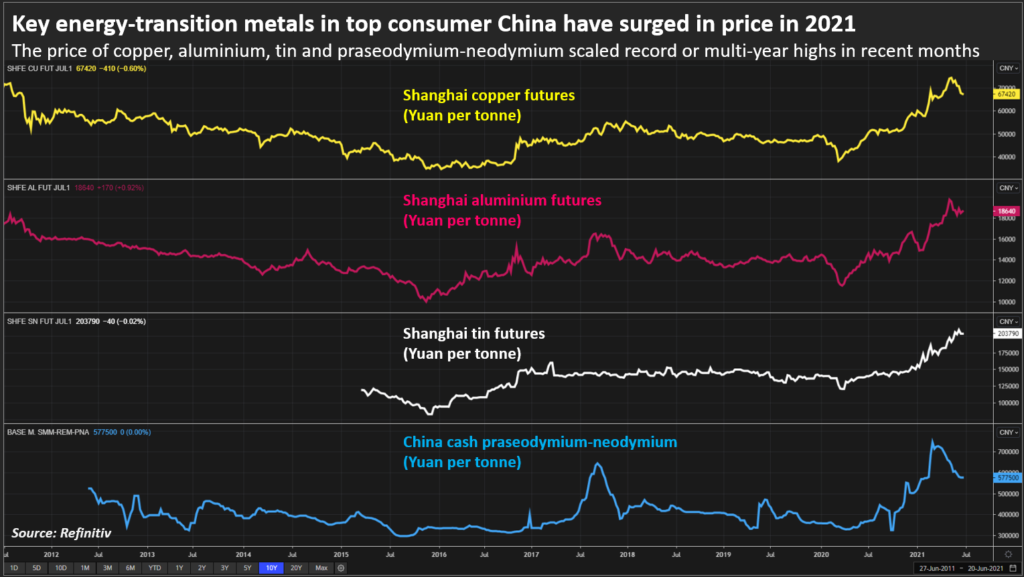

Buoyed by powerful demand expectations as the world moves away from reliance on fossil fuels, prices of many industrial metals rocketed, but future price rises are likely to be limited to a select few energy transition ingredients.

The narrative of a synchronised upswing, characterised by some as a supercycle, is at odds with expectations shortages of materials will occur at different times.

“Energy transition metals will take off big time, but not all at the same time,” Wood Mackenzie analyst Julian Kettle said.

The easing of coronavirus restrictions and robust manufacturing demand for industrial metals ignited a speculative rally that has cooled.

Copper, aluminium and tin prices are above the levels needed to incentivise new capacity.

Rare earths are not yet at incentive levels.

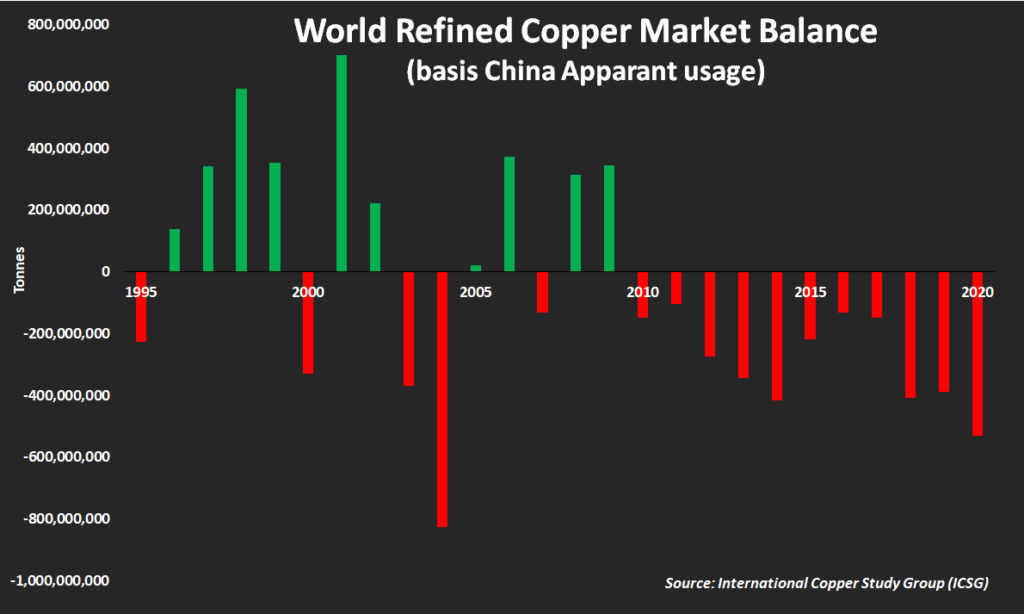

Copper

Wood Mackenzie estimates that copper demand from renewables, energy storage and transmission and electric vehicles and charging infrastructure will more than double to 8.6 million tonnes in 2025 from 2020 levels under a scenario that limits global warming to less than 2˚C.

WoodMac forecasts 15.1 million tonnes will be consumed in energy transition applications by 2030.

New supply will be needed, but miners are wary of making investments after their experience of the last decade when investment collided with peak demand, leading to a collapse in prices and revenues.

Rising costs associated with environment, social and governance (ESG) issues add to the challenges miners face.

Resource nationalism whereby countries aim to take a bigger slice of miners’ revenues is also an obstacle.

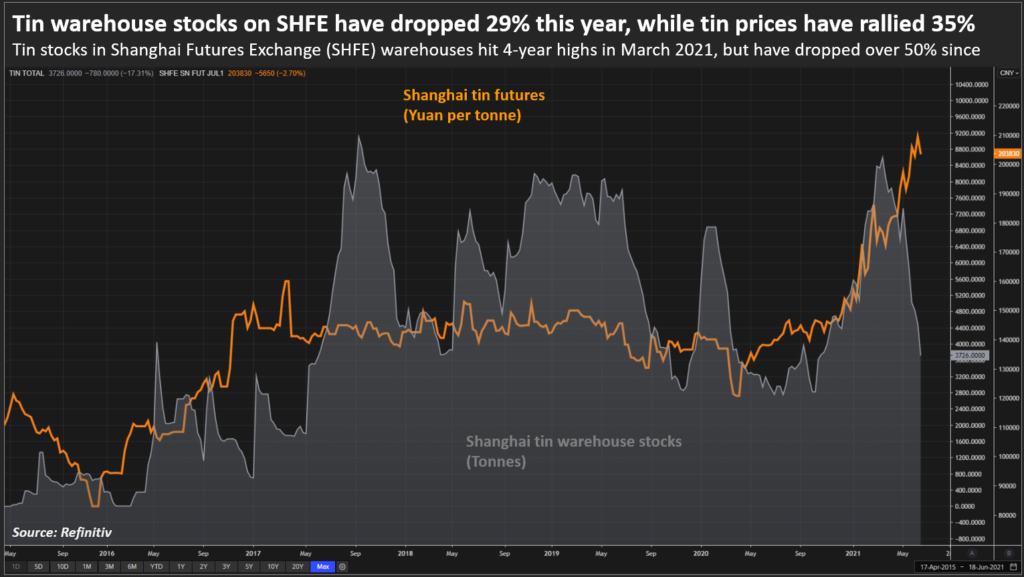

Tin

Tin is the forgotten foot soldier of the energy transition, which will be the largest long-term demand driver for the soldering metal, Kettle said.

Nearly 50% of demand for tin, estimated at around 340,000 tonnes this year, is for electronic components, many of them vital for the low carbon economy.

Without tin, electrons don’t flow and electric vehicle batteries don’t charge.

Jeremy Pearce, analyst at the International Tin Association, estimates electric vehicles, renewables and energy storage use around 45,000 tonnes of tin a year.

“This could increase to up to 70,000 tonnes per annum in 2025 and perhaps 100,000 tonnes per annum in 2030.”

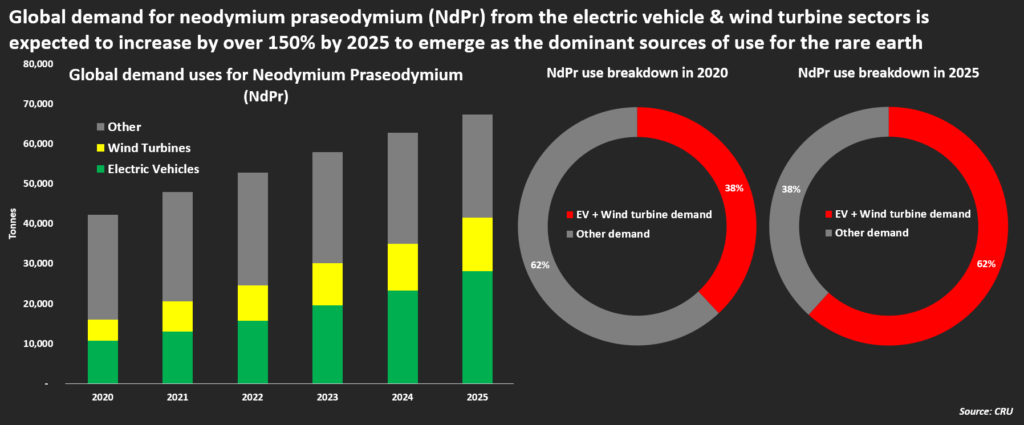

Rare earths

Magnets made with neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr) are used in wind turbine generators and electric vehicle motors.

Electric vehicles made without rare earths are less efficient as the battery pack needs to be about 30% larger to cover the same distance, analysts say.

CRU analyst Daan de Jonge sees the energy transition lifting demand and prices for NdPr over coming years to levels that incentivise new projects, but cites caution.

“China owns the intellectual rights regarding processing of rare earths. They invested in the technology when others wouldn’t,” de Jonge said.

China’s dominant position in rare earth supply is worrying for other countries.

Processing rare earths is complicated because there are many metals in the same ore, as opposed to copper ore, for instance, which may contain only cobalt or molybdenum.

CRU forecasts NdPr demand from electric vehicles and wind turbines at 41,575 tonnes or 62% of the total in 2025, from 20,544 tonnes or 42% of the total this year.

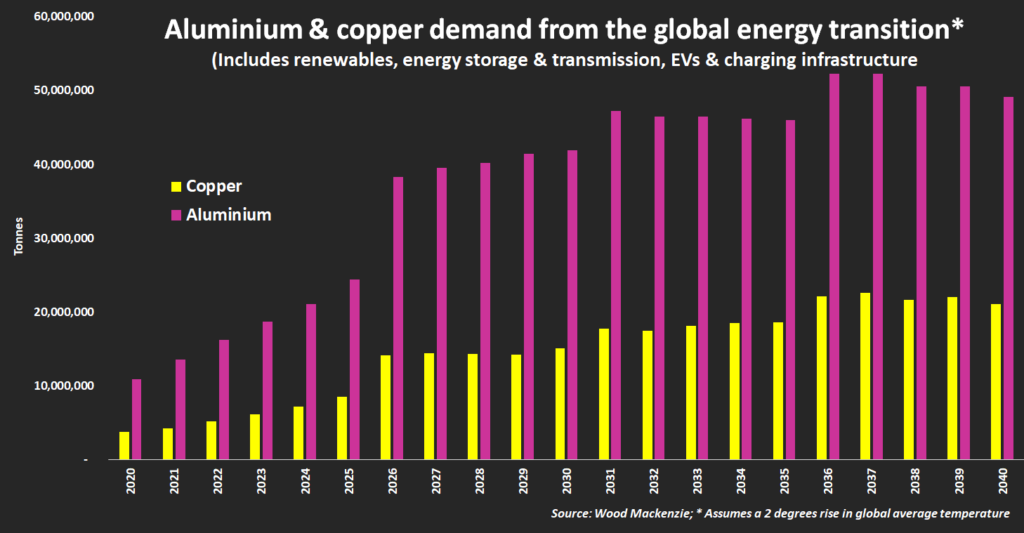

Aluminium

Aluminium weighs about one-third as much as steel per cubic foot, enabling “lightweighting” of electric vehicles and increased mileage before batteries need to be recharged.

Under Wood Mackenzie’s 2˚C scenario, demand from renewables, energy storage and transmission and electric vehicles and charging infrastructure will climb to 24.4 million tonnes in 2025 and 42 million in 2030 from 13.5 million tonnes this year.

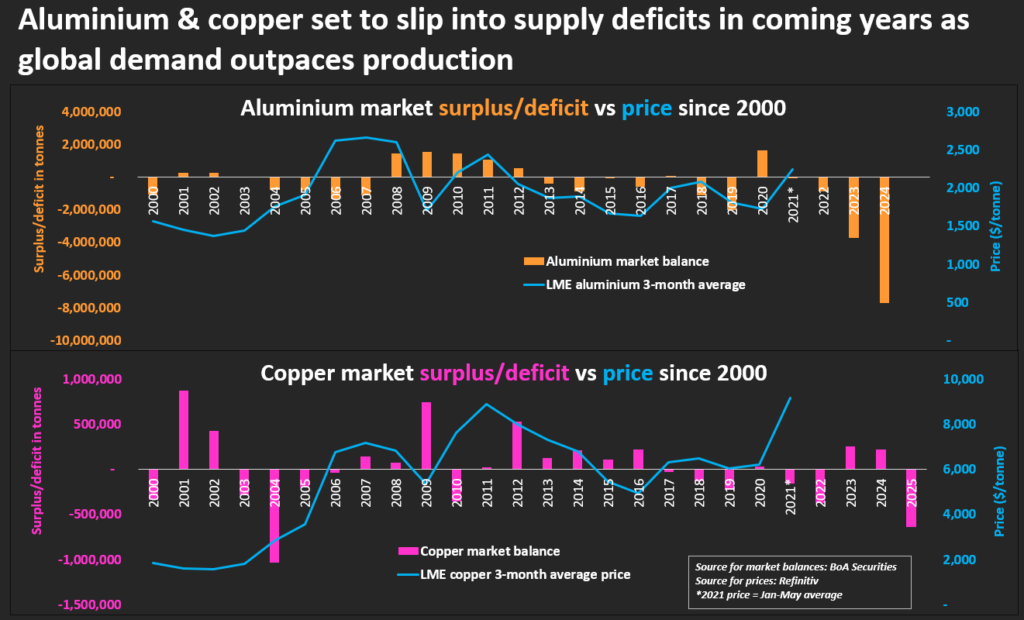

Global total aluminium demand is expected at around 76 million tonnes in 2025, up 10% from this year, leaving a supply deficit of about two million tonnes.

Predicted shortages are partly due to China’s carbon emissions targets. China’s Nonferrous Metals Industry Association (CNIA) has set a provisional goal to bring emissions to a peak by 2025.

“Total carbon dioxide emissions from smelting were 420 million tonnes this year,” ING analyst Wenyu Yao said. “A peak by 2025 suggests China should cap smelting capacity under 45 million tonnes.”

(By Pratima Desai and Mai Nguyen; Editing by Veronica Brown and Barbara Lewis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments