Gold revaluation & the hidden motive behind central banks’ gold buying

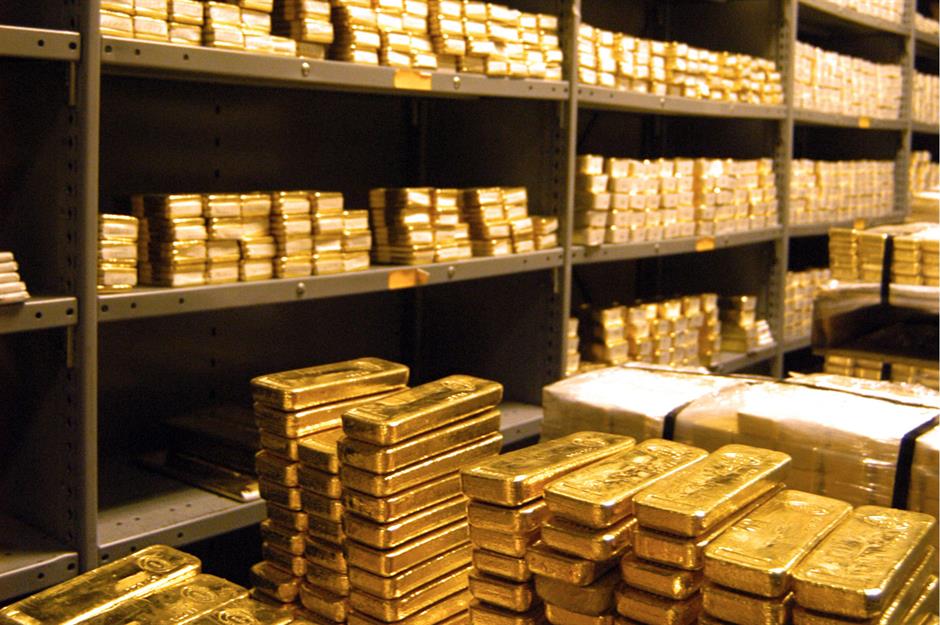

It’s no secret that central banks around the world are buying up gold.

In the first three months of the year, central banks bought a combined 228 tonnes, the most ever seen in a first quarter, World Gold Council data revealed.

This follows up on what was already a record year in 2022, during which 1,136 tonnes of gold worth some $70 billion were added to the banks’ reserves. Compared to the 450 tonnes bought during 2021, that represents a whopping 152% year-on-year increase!

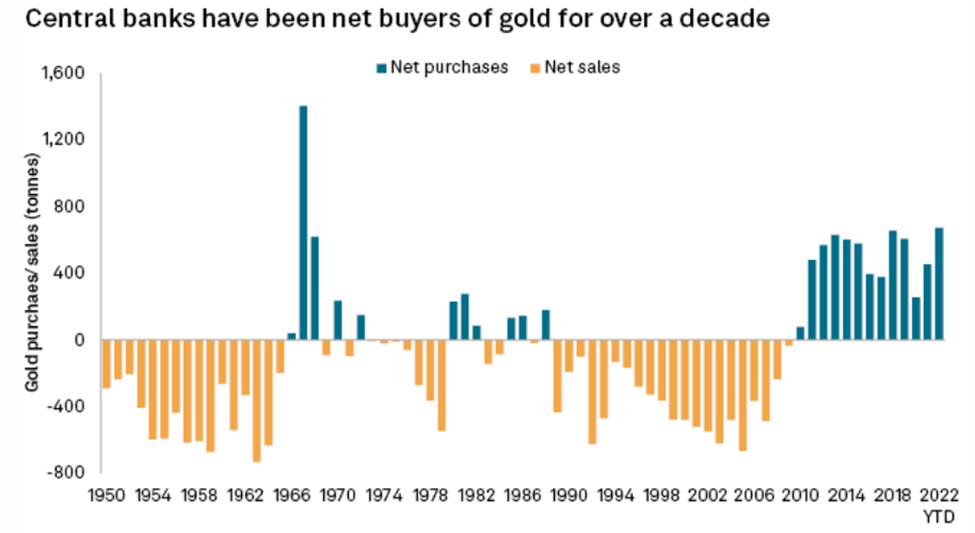

The pace and consistency at which central banks are now accumulating gold, as far as we can tell, is unprecedented, given they’ve mostly been sellers throughout history. But the recent transactional trend, in particular over the past 30 years, illustrates a dramatic shift in the official attitude towards gold.

Back in the early 1990s and 2000s, central banks were continuously selling off gold as strong economic growth during that time rendered bullion less attractive than currencies in many places. Some, such as those in Western Europe, were even selling hundreds of tonnes a year!

Then the 2007–08 financial crisis came, triggering a complete 180 in the official banks’ approach to gold. From 2010 onwards, central banks have been net buyers on an annual basis. About 80% of the central banks currently hold gold as part of their international reserves.

Why buy gold?

Central banks like gold because the metal is expected to hold its value through turbulent times and, unlike currencies and bonds, it does not rely on any issuer or government. It also enables central banks to diversify away from assets like US Treasuries and the dollar.

And in the aftermath of what’s considered the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, it would make sense to stockpile bullion for its safe-haven qualities; but this may not tell the entire story.

After all, as WGC data showed, central banks have been stashing gold for well over a decade, even during periods when the global economy has looked relatively healthy. “It predates COVID. It predates sanctions,” said Joe Cavatoni, chief market strategist for North America with the WGC, in reference to the next wave of crises that sparked safe-haven demand.

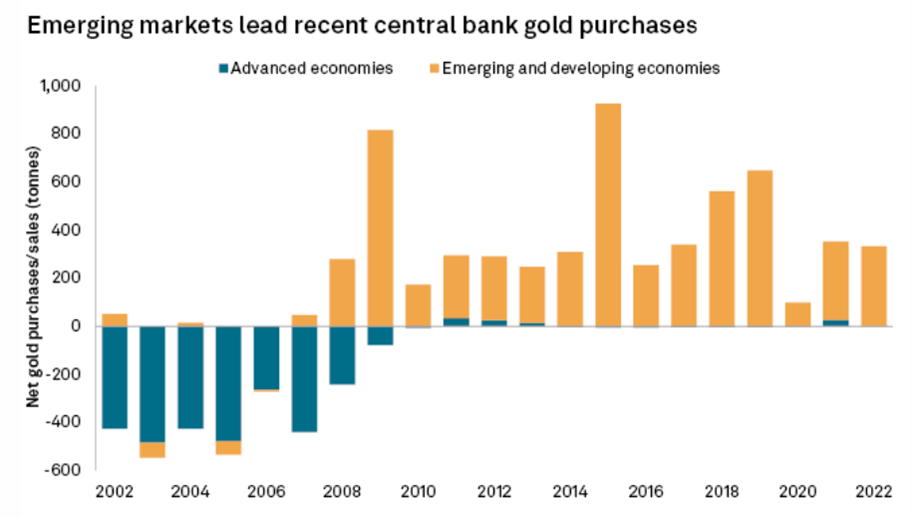

The main driving force behind the new wave of gold buying was the so-called “emerging market/developing economies”, which operate a bit differently to Western banks as their economies are under greater risk during geopolitical struggles, and they also tend not to trust the USD reserves.

De-dollarization

It’s no surprise then to see Russia and China being the most aggressive gold buyers in recent years, accounting for about half of the total tonnage bought worldwide over the past two decades. Behind them was Turkey, which ramped up purchases to a world-leading 148 tonnes last year.

It’s worth noting that gold-buying statistics like the one above only reflect what’s being reported by central banks; analysts believe there is more gold, likely much more, being purchased by the likes of Russia and China than what’s made public.

The rationale behind these purchases, according to industry experts, is to protect against foreign seizures, as many of these banks want to hold more bullion as a buffer against any current or future sanctions. The Central Bank of Russia, for example, can use gold to replace the USD (i.e. “de-dollarization”) and circumvent Western sanctions when it comes to international trade.

“We think this trend of central bank buying is likely to continue amid heightened geopolitical risks and elevated inflation,” UBS said via a Business Insider report. “In fact, the US decision to freeze Russian foreign exchange reserves in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine may have led to a long-term impact on the behavior of central banks.”

In short, there’s an added layer to the motives behind most of the gold buying by today’s central banks.

Forbes Finance Council’s Sanford Mann describes the distinction perfectly: “Where US, European and Asian banks tend to see gold as a historical legacy asset, EMDE banks tend to see it as a strategic asset.”

“As globalization accelerates, the non-G-10 nations are expected to ‘re-commoditize’ and ramp up gold holdings,” Nicky Shiels, head of metals strategy at MKS PAMP, mentioned to Forbes.

We also can’t forget that gold is one of the best hedges against inflation. Consider this: in the 110 years since the US Federal Reserve was created, the USD has lost 99% of its purchasing power, while gold has barely been touched by relentless annual inflation. Inflation is also a main reason why countries like Turkey, which saw an over 80% rise in price levels, bought more gold last year.

But what if all of these motives don’t fully explain the recently relentless, accelerated gold buying? After all, central banks are experiencing by far the longest period of net purchases on record since 1950.

Most prerequisites for past gold purchases (risk of financial turmoil, inflation etc.) are still prevalent, yet the buying patterns over recent years display something stronger — another motive, per se — that propels banks to buy more gold.

Gold to cover losses

At AOTH, we’re inclined to believe that all this gold buying has to do with the massive losses central banks have accrued over the years – gold can be used to help them get out of debt.

The idea is quite simple; It revolves around using the increased value of the banks’ gold holdings (i.e. what investors call “unrealized gains”) to write off sovereign bonds. This practice would be especially applicable to the European central banks, as they accumulated most of their bullion during the Bretton Woods era when gold was valued at a measly $35 an ounce.

Now that the metal is trading at about $2,000/oz, central banks are now sitting on unrealized gains worth hundreds of billions of dollars (Germany, for example, bought its gold for €8 billion euros; today they’re worth around €180 billion euros). Of the many ways in which these humongous gains can be “weaponized” to their advantage, banks can simply use them to cover debt.

We also need to remember that the government-debt-to-GDP ratios in many countries are at all-time records, so this is a critical time for global central banks to make a call on whether to write off sovereign debt and provide relief to their respective governments.

But just how are central banks able to do that? The solution lies in a simple maneuvering of the balance sheet.

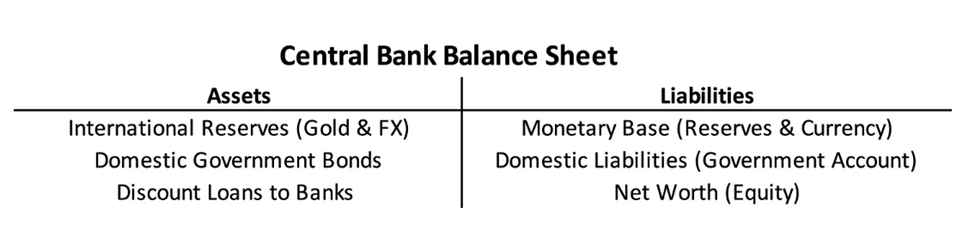

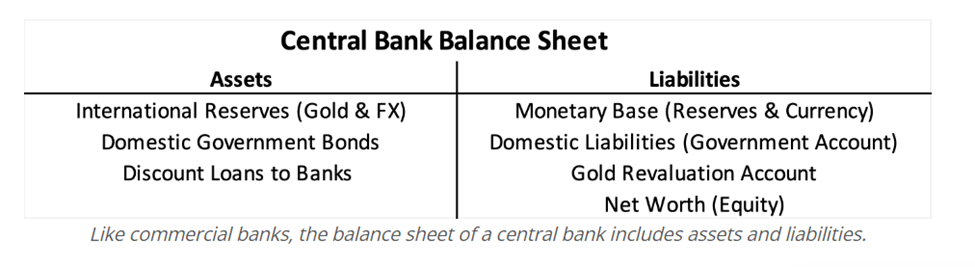

We probably know from accounting classes that pretty much every institution uses a balance sheet to keep track of their financial health, and the central banks, being as big as they’re, are certainly no different.

A balance sheet is divided into two parts: assets and liabilities. The former consists of international reserves (gold and foreign exchange), domestic government bonds, and loans to banks. The latter includes the monetary base (reserves and currency), a deposit account for the government, and equity.

Below is a generalization of what a central bank’s balance sheet would look like:

The key here, is the total assets must always equal total liabilities for the accounts to balance (hence, a “balance sheet”). So, for a central bank to write off government debt (i.e. bonds), something on the liability side must also be written off, as part of the double-entry bookkeeping.

While it’s technically possible the bank can use its capital/equity, that would still create too little of a buffer to create any relief of substance. Even then, operating under negative equity could also jeopardize the central bank’s credibility.

Pumping more into the monetary base is also not an option. As we’ve come to realize, the financial packages used to lift economies out of the COVID pandemic have led to high inflation levels that central banks are still fighting to contain.

This brings us to gold, which offers a far better option for its massive unrealized gains.

Gold revaluation account

Since bullion is the only international reserve asset not issued by a central bank and can’t be printed, there’s actually no limit to its value denominated in fiat currencies. So when the gold price rises, like it has done this year, the value of the gold on the asset side of the balance sheet increases.

But to balance out the increase in gold’s value, an equal increase must be recorded on the liability side. To do that, central banks can use what’s referred to as a “gold revaluation account”, or GRA, to register the unrealized gains (see below).

In a way, a GRA functions like equity, and it can inflate a bank’s balance sheet because it effectively has no limit, as its value is synced with that of gold (i.e. when gold price goes up, the GRA goes up). Though should gold prices plummet, it could also sink the balance sheet, as the GRA would turn negative and eat into a bank’s net worth.

Because of this, GRAs have been prohibited within the European Union. As the current EU law states: “There shall be no netting of unrealized losses in any one security, or in any currency or in gold holdings against unrealized gains in other securities or currencies or gold”.

In other words, any unrealized gains in gold can only be used for unrealized losses in gold, not for losses in assets such as US dollars or European bonds.

But as we know, rules are there to be changed, especially when push comes to shove during a mounting debt crisis. Interestingly, GRAs have been used once before. In the 1930s, gold was “revalued” by central banks after countries went off the gold standard and devalued against gold. Eventually, the banks re-pegged their currencies to gold at a higher price, leaving GRAs to be used as they saw fit.

Euro banks to revalue gold?

Although no central bank has so far openly talked about using GRAs to cover its own losses or cancel sovereign bonds, it doesn’t mean it’s not on their minds.

Last fall, the Governor of the Dutch central bank was interviewed about how it plans to deal with the bank’s balance sheet, in which the capital position is running close to negative due to losses. DNB president Klaas Knot had this to say:

“The balance sheet of the Dutch central banks is solid because we also have gold reserves and the gold revaluation account is more than 20 billion euros, which we may not count as equity, but it is there.”

When asked by the interviewer if selling gold is an option, Knot emphatically said “No, we’re definitely not going to sell.”

This is quite significant, because it means the bank is aware of the possibility of using GRA as a solvency backstop; after all, taxpayers can’t always be relied on to bail out their central banks and government.

Another central bank that didn’t rule out a gold revaluation is Germany’s. In late 2021, Jan Nieuwenhuijs, gold analyst at Gainesville Coins, emailed the Deutsche Bundesbank asking if they considered this option, to which the bank replied:

“At this stage, we prefer not to speculate about any potential decisions … that might or might not be taken in the future. In general the accounting rules are set by the ECB Governing council in accordance with the limits set by the European Treaties.”

This response, as Nieuwenhuijs later wrote in his blog in February 2022, was a “signal for the market to revalue gold”, saving the Bundesbank the hassle of doing it themselves (i.e. printing money to buy gold). According to the analyst, the use of phrases like “at this stage” and “in general” meant that the bank is simply not ruling anything out.

Nieuwenhuijs also reminded us what former Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann wrote back in 2018, calling gold “the bedrock of stability for the international monetary system“ and a “major anchor underpinning confidence in the intrinsic value of the Bundesbank’s balance sheet.”

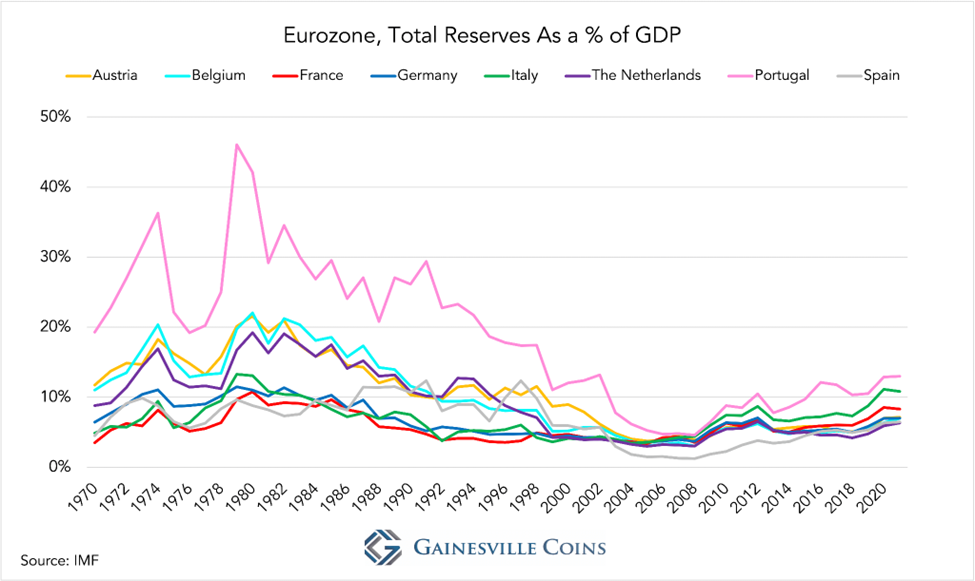

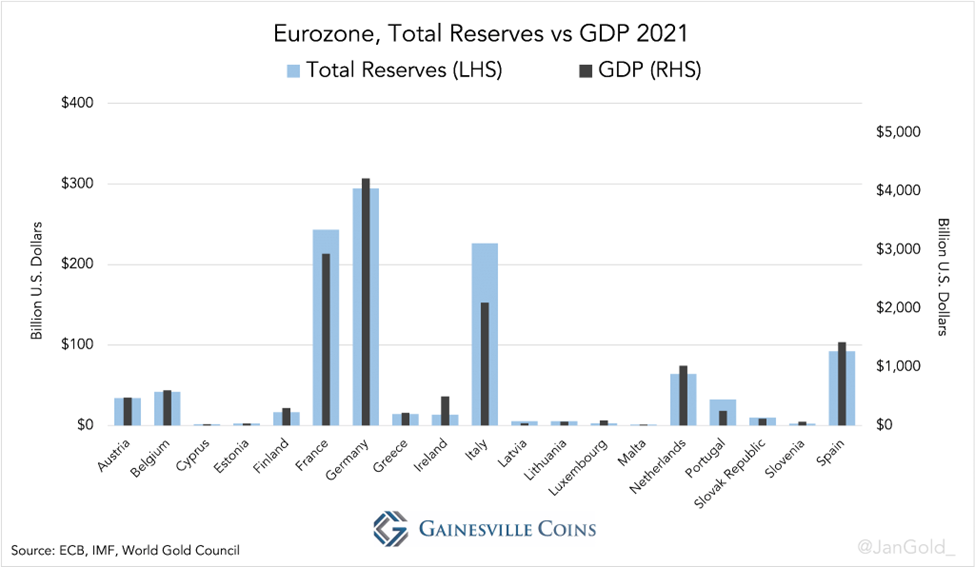

Later in October 2022, the analyst wrote in another blog entry that European central banks have equalized, proportionally to GDP, their gold reserves among each other in the past decades. “This was done for all to enjoy the same relative gain in their GRAs when revaluing gold,” he speculated.

And it’s not just the European central banks that could start reevaluating gold. Nieuwenhuijs revealed in his recent article that one Caribbean nation, namely Curaçao and Saint Martin, dampened losses in 2021 by using a small portion of its GRA. This was done by simply selling and immediately buying back the same amount of gold the central bank held for a realized gain.

What about Fed?

Shifting focus closer to home, things get a little more tricky. The US has long opposed a gold revaluation dating back to the 1970s, as this would damage the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

So, for the Federal Reserve to revalue its gold would then present a separate balancing act to just equating assets with liabilities. But time is not really on its side, given the rotting health of the US banking system.

This year, we saw two of the biggest bank collapses in US history; the ferocious run at Silicon Valley Bank in March alone cost the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation an estimated $20 billion to cover. During that month, at least $229 billion was wiped off the market value of America’s banks, a decrease of nearly 20%!

The SVB failure casts light on an overlooked risk within the US banking system, in particular the central bank’s approach to monetary policy.

When interest rates were low and asset prices high, banks like SVB loaded up on long-term bonds. Then the Fed started to raise rates at its sharpest pace in four decades, and subsequently bond prices plunged, and banks were left with huge losses.

Since America’s capital rules do not require most banks to account for the falling price of bonds they plan to hold until they mature, then once they’re forced to sell bonds to cover deposits, these “unrecognized losses” become real.

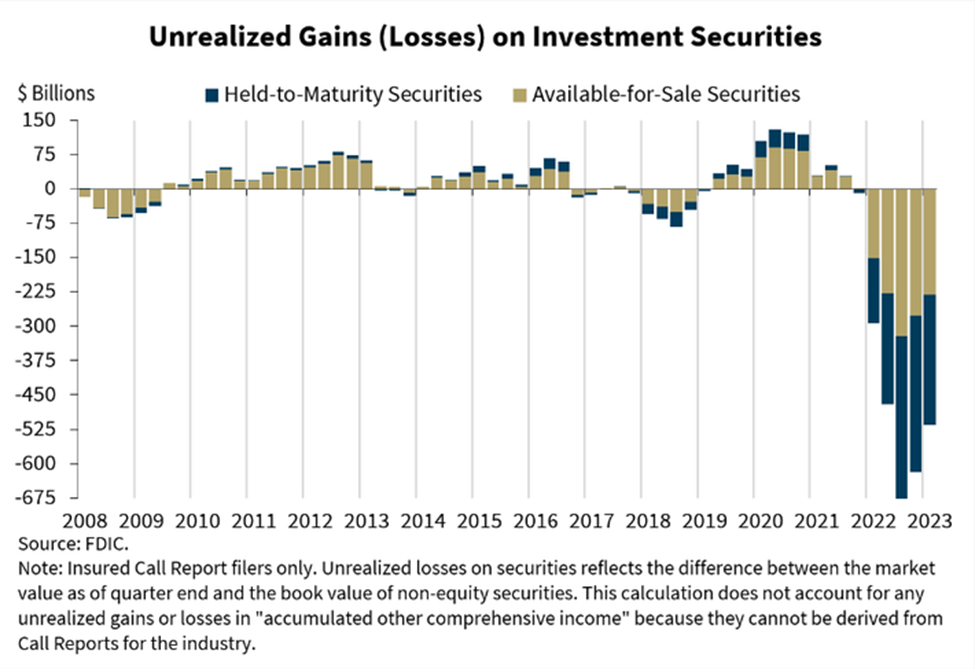

According to FDIC estimates, the unrecognized losses across the banking system stood at $620 billion at the end of 2022, which is equivalent to about a third of the combined capital cushions of the US banks. However, some experts believe the figure is understated, with two recent estimates suggesting the outstanding losses could be as much as $1.7 trillion.

The scary part is that the unrecognized losses could only swell. Many banks were encouraged to use deposits to buy long-term bonds during the low-interest-rate period, which makes all of them vulnerable.

The losses would then trickle down to the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, because technically the US central bank is the lender of last resort to stop bank runs.

A March 2023 report by Thomson Reuters stated that “The estimated level of unrealized losses on bank balance sheets and borrowing by banks at the Federal Reserve’s discount window and from the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHL Banks) point to a financial situation in which many regional and smaller institutions are in need of financial assistance — warranted or not.”

Recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund confirmed that there are indeed some serious cracks in the US banking system. Below is an excerpt of what the IMF researchers wrote in their report:

“First, a higher path for interest rates could reveal larger, more systemic balance sheet problems in banks, nonbanks, or corporates than we have seen to date. Unrealized losses from holdings of long-duration securities would increase in both banks and nonbanks and the cost of new financing for both households and corporates could become unmanageable.”

In layman’s terms, bond prices have an inverse relationship to interest rates, and so when the Fed raises rates, that dents the value of assets held by banks, including that of the Fed itself.

Indeed, the Fed has experienced significant operating losses over the last six months, which have exhausted capital. Newly released financial statements reveal that the Fed is carrying $330 billion in unrealized losses on its holdings Treasury and mortgage-backed securities.

But Bill Nelson, chief economist at the Bank Policy Institute, said that adjusting for the appreciation in the Fed’s assets, the unrealized losses could be even larger at $458 billion.

The Hill contributor Thomas Hogan says this is the product of the Fed’s quantitative easing programs that took place in 2020-2021, when market rates on long-term Treasury bonds fluctuate mostly in the range of 1.5 to 2.0 percent.

At the time, the Fed was paying interest on bank reserves and overnight reverse repurchase (ONRRP) agreements of 0.15 or less, so it profited on the difference between the higher rate it received from its bond purchases minus the lower rates it paid on reserves and ONRRPs.

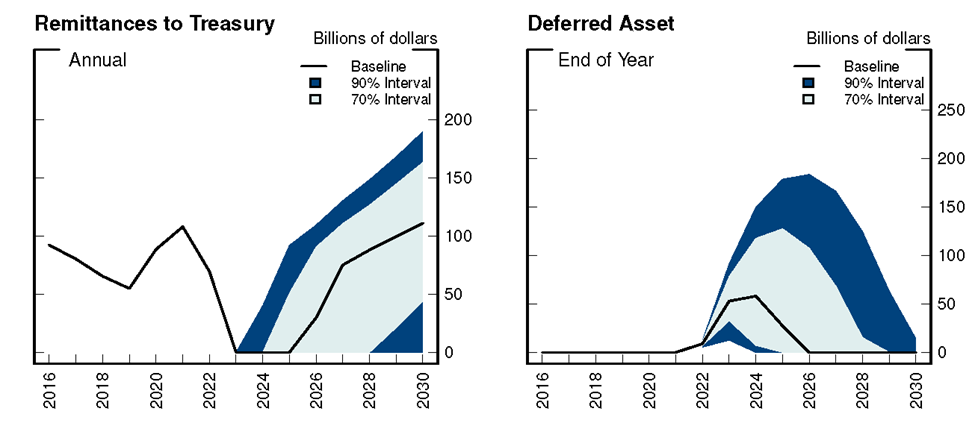

But now that the Fed has raised the interest it pays to 4.8 percent on ONRRPs and 4.9 percent on bank reserves, it’s racking up losses since the rates it earns on its QE purchases remain mostly unchanged.

A rough estimation by Hogan has the bonds paying an average rate of 1.75 percent, while the average rate paid on bank reserves and ONRRPs is 4.85 percent, so the Fed is paying about 3.1 percent per year more than it receives on its $7.88 trillion dollar securities portfolio. That’s a loss of $244 billion per year, which nobody seems to be talking about.

Hogan goes as far as to say that the US central bank is bankrupt, owing the Treasury more than $48 billion, which exceeds the bank’s total capital.

In practice, the bank could create fictitious accounts in the assets column (called “deferred assets”) to offset the increased liabilities. As the Fed describes, “the deferred asset is the amount of net earnings the Reserve Banks will need to realize before their remittances to the US Treasury resume.”

The advantage to deferred assets is that the Fed can continue its normal operations without disruption, although considering the 40-year high inflation, its recent performance has been less than ideal, as Hogan points out.

The disadvantage is that, at a time when the Fed is already worsening the US fiscal position by raising interest rates (and, therefore, interest payments on the federal debt), it is further robbing the Treasury of revenues by deferring them into the future. Those deferred payments are being shouldered by American taxpayers until the Fed’s remittances resume.

In short, the Fed is in deep water. So far, it has already accrued $48 billion in deferred assets, and the amount is only getting larger.

Could the bank also contemplate revaluing its gold to offset its losses? The possibility is there. After all, the US does hold by far the largest gold reserves at 8,133 metric tonnes, worth about $474 billion on the market. It should be noted that until this day, the US records its gold reserves at a statutory price of $42.22/oz.

New version of gold standard

Of course, everything’s just speculation at this point.

What we can conjecture is that something is at least brewing in the Eurozone; using gold as a hedge against economic risks can only explain so much of the recent buying patterns

We mentioned before that many Western European central banks were selling gold in the 90s, and the amount they sold tended to equalize their reserves among each other and large economies outside the continent. Then the 2008 financial crisis happened, prompting them to change their public stance on gold.

In recent years, countries like Germany and France have started to repatriate their gold and upgrade their reserves up to wholesale industry standards. This, as Nieuwenhuijs said in a previous analysis, is an indicator of European banks preparing for a new “gold standard” through a revaluation of gold.

To do that, though, gold must be spread evenly across the Eurozone countries so that everyone can benefit to the same degree. Nieuwenhuijs believes there is already a mechanism in place to “harmonize” their gold reserves, drawing evidence from statements shown on various banks’ official websites.

In a nutshell, Nieuwenhuijs says there seems to be some sort of guideline for the Euro banks to hold an appropriate amount of gold relative to GDP, but also relative to total international reserves.

When he tried to get confirmation of this “Europe’s balancing project” from a former central banker, he was told that they’re not legally allowed to openly talk about it, though the banker did hint at the existence of such guideline when the banks were selling gold during the 90s.

A deeper dive into data showing how much gold the Eurozone nations are holding relative to their reserves, as well as the ratio of total reserves to GDP, backs up Nieuwenhuijs’ hypothesis, which is: Gold reserves evenly spread across nations, proportionally to their GDP, allows a smooth transition towards a global gold standard.

Conclusion

Long story short, it can’t just be a coincidence that global central banks are buying this much gold, at the current pace, at a time when they’re making significant losses.

Putting 2 and 2 together, we can conclude that a gold revaluation must be at least in the minds of central bankers, even if they don’t/can’t say it publicly.

And it’s not like this would be the first gold revaluation in history anyway.

In the early 1930s, for example, the US government demanded citizens turn in their gold for $20.67 an ounce, then the very next year revalued it to $35 an ounce, which eventually became the price used in the Bretton Woods system.

Just in the last couple of years, Turkey requested its citizens sell their gold to the government to help support the plummeting Turkish lira (recall that Turkey was also the biggest net buyer of gold last year). The same thing could happen in any place, or even on a global scale.

(By Richard Mills)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Phil Crincoli

What’s the bottom line? Future precious metals seizures?

What would be exempt?