Global output drop fails to disperse aluminium gloom

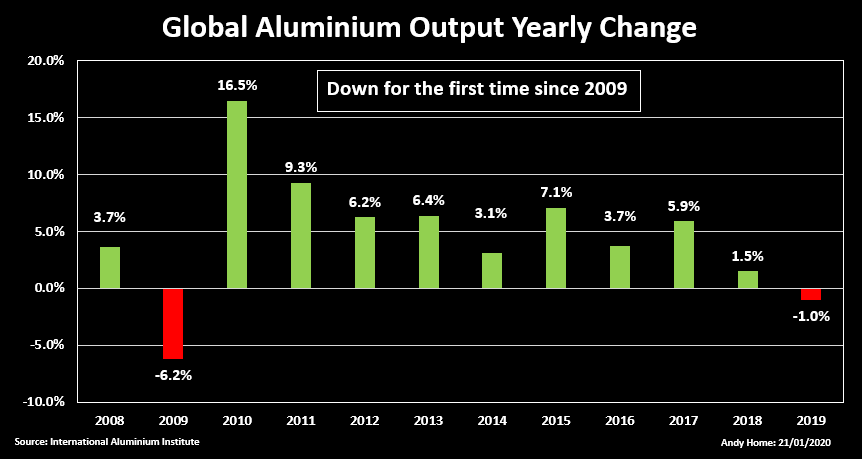

Global aluminium production fell by 1.0% last year in its first annual contraction since the Global Financial Crisis in 2009.

That should have been good news for the aluminium price, but London Metal Exchange three-month metal spent most of last year grinding steadily lower.

The slide in October took prices to a two-and-a-half year low of $1,705 per tonne and they have struggled to stage any convincing recovery, last trading around $1,820.

The problem is that a rare year of lower production coincided with an equally rare year of weak aluminium demand.

Moreover, last year’s fall in production was largely down to China, the world’s largest aluminium-producing nation, and there is a market consensus that Chinese production growth has only paused before accelerating again this year.

That leaves non-Chinese producers under pressure to reduce output as the survival race down the cost curve resumes.

Chinese production growth pauses

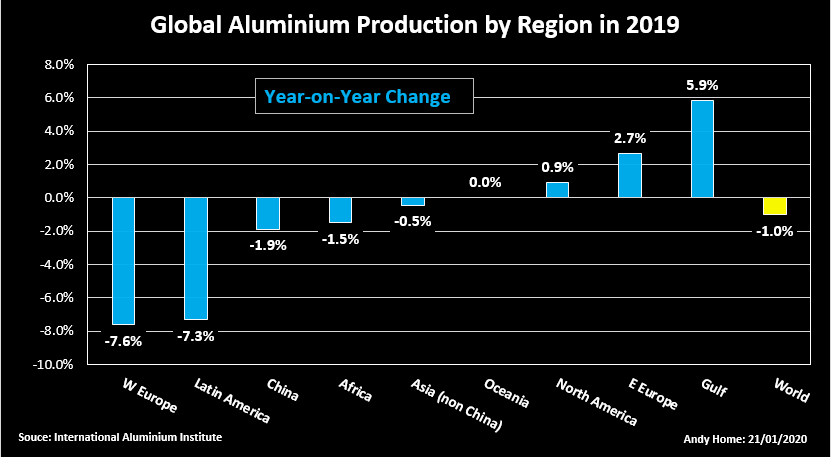

China’s production of primary aluminium fell by 1.9% last year, according to the International Aluminium Institute (IAI).

The IAI’s estimate of national output last year was 35.8 million tonnes, slightly higher than the official assessment of 35.0 million tonnes released by the National Bureau of Statistics.

However, both agencies agree that China’s giant aluminium sector produced less metal last year than in 2018.

Last year’s fall in production was largely down to China, the world’s largest aluminium-producing nation

That marked a rare reversal for a country that has grown its smelting capacity at breakneck speed to account for around 56% of global output.

The rest of the world would love to believe Chinese output is peaking under the constraints of Beijing’s structural reform of the sector.

However, there is little evidence this is anything other than a pause in a relentless uptrend.

Last year’s fall in output partly reflected two big one-off smelter hitches.

Top producer China Hongqiao Group’s facilities were hit by flooding in August and Xinfa Group also closed pot lines due to an explosion a week later. In both cases remediation work and a full restart of the affected potlines would have likely taken several months, acting as a drag on national output growth.

Although the Chinese government has set a capacity cap on aluminium production, the line in the sand has been drawn at 45 million tonnes, meaning there is plenty of room for higher output over the coming years.

Analysts at CRU research house are looking at a potential 5% jump in Chinese production this year as new capacity and replacement capacity comes onstream.

The concern is renewed production growth generates a pick-up in China’s exports of semi-manufactured aluminium products, which were 1.3% lower in the first 11 months of last year after 24% growth in 2018.

Rest of the world flat-lines

Production outside China rose by just 0.2% to 26.1 million tonnes in 2019.

The weak growth reflected a number of smelter disruptions rather than any structural shift in Western production.

A 7.3% drop in Latin American output, for example, was largely down to curtailed output at the Albras smelter in Brazil.

Hydro reduced throughput at Albras to around 50% of capacity early in 2018 to match a court-mandated cut at the Alunorte alumina refinery, which supplies raw material to the smelter.

Alunorte is only now ramping back up full capacity, allowing the smelter to lift its own operating rate.

There were once seven operating smelters in Brazil. Today there are two, meaning the Albras plant outage had a disproportionate impact on regional production.

North American production growth of 1.0% similarly masked several individual smelter stories.

The partial restart of Alcoa’s Warrick smelter in Indiana was offset by low production at the Becancour smelter in Canada, where an 18-month union walk-out only ended in July, and at Rio Tinto’s Kitimat smelter due to earlier-than-expected potline relining work.

Such operational problems served to mask an underlying upwards creep due to expansions in both Russia and the Gulf region.

Eastern European production grew by 2.7% last year, reflecting the ramp-up of new capacity at Rusal’s Boguchansk smelter.

Gulf operator Aluminium Bahrain, meanwhile, last year brought on line a sixth potline with 540,000 tonnes of capacity, spurring the fastest regional growth rate last year of almost 6%.

Cost curve pressure

Smelter hits impacted production in both China and the rest of the world in 2019. A less troubled operational year and new capacity in both halves of the aluminium universe promise oversupply in 2020.

Demand last year was extraordinarily poor by aluminium’s historic standards and although it is expected to recover this year, it may not be enough to absorb the surplus metal.

Alcoa told analysts on last week’s results conference call it expects global demand growth to be in a 1.4-2.4% range this year after contracting in 2019.

However, the company still anticipates a global primary aluminium surplus of between 600,000 and one million tonnes.

Look no further to understand why the aluminium price is struggling to generate any upside momentum.

Indeed, it may have to fall further to rebalance the market, according to analysts at Morgan Stanley. They warned last month that “supply cuts in excess of one million tonnes are needed to prevent a drop to our bear case of $1,657 per tonne in early 2020”.

The likes of Alcoa and Rio Tinto seem to be of the same mind. Both companies are conducting strategic reviews of their smelter assets with all options, including curtailment and closure, on the table.

In a world of bombed-out pricing, survival means moving down the cost curve to preserve margins.

And if that sounds familiar, it’s because global aluminium producers have been here before.

Neither they nor most other analysts expect last year’s pause in global production growth to last.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Barbara Lewis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments