Global diamond trade fractures under the weight of Russia sanctions

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is fracturing a billion-dollar trade that spans the permafrost-laden diamond mines of Siberia, secretive trade houses in Antwerp, dusty polishing powerhouses in India and New York’s glittering designer jewelry stores.

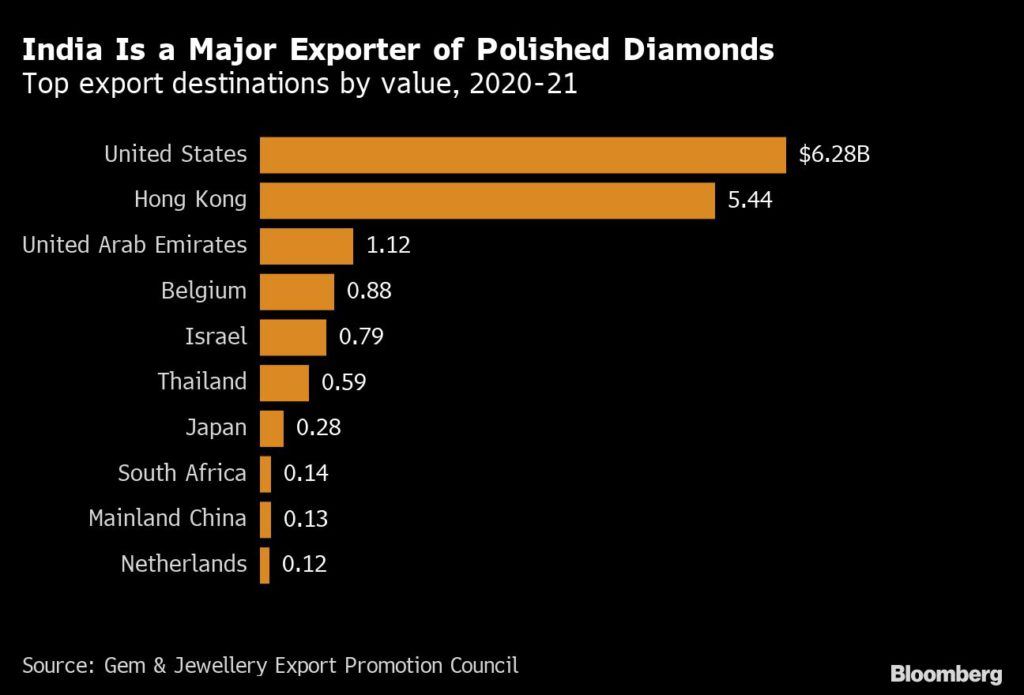

Russian mining giant Alrosa PJSC supplies about a third of the world’s raw gems, and US sanctions against the company are causing panic in the industry. Firms from Tiffany & Co. to Signet Jewelers Ltd. have announced plans to suspend sales of Russian diamonds. With wedding season looming in America, desperate delegations have been seeking a workaround from India, the world’s largest exporter that cuts and polishes nine of 10 stones.

The US relies on India for close to half its diamonds. That makes New Delhi an unmatched stakeholder in managing the fallout and keeping shops on Fifth Avenue stocked. Disruptions could crimp supplies across North America and cost India $2.5 billion this quarter, or nearly 10% of its annual sales. As pandemic restrictions ease, Signet and other jewelers expect 2.5 million weddings in the US this year, the highest number in four decades.

In the Indian city of Surat, one of the world’s largest polishing hubs, the diamond bazaars have gone quiet in recent weeks. Workers sit idly and grumble over cups of tea. Imports of new stones are down. Prices have fallen. Practically everybody has the same complaint: Sanctions have pushed exporters into a tough spot.

“Normally the streets are chock-a-block with buyers and sellers,” said Manish Jain, a trader who was commiserating with several others on a hot day last month. “Prices suddenly dropped after the war began and we are now left holding high-valued stocks with no buyers.”

For now, a caveat in US sanctions allows imports that are “substantially transformed” in a country like India, though lawmakers are pushing to close loopholes. But polishers say some clients have started refusing Russian-mined stones, characterizing them as conflict diamonds. With so much uncertainty, India’s traders are preparing to mark the origin of every stone — re-routing Russian ones to friendlier markets in China, Southeast Asia, or the United Arab Emirates.

India is still exporting Russian diamonds to the US since the current stock was obtained pre-sanctions. But that supply will run out by the first week of June, according to Vipul Shah, vice chairman of India’s Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council. And while many European countries have yet to restrict imports of Russian luxury goods, the list is growing there, too. The UK announced that high-end items from diamonds to caviar would be prohibited or heavily taxed.

De Beers, the world’s second major diamond provider, is also limited in cranking out more gems. The company now only carries working inventory stocks and its mines are running at full tilt. There is little chance of material increases in supply before 2024, when an expansion at its flagship South African mine is slated for completion.

“It’s very difficult to see us bringing on any new production,” Bruce Cleaver, chief executive officer of De Beers, said in an interview in Cape Town.

Losing access to Russian diamonds over the long term would devastate the industry, Shah said, jeopardizing thousands of jobs in India and hitting major trading centers across the world.

Alrosa canceled its last sale in April and is unlikely to sell any large volumes again this month, according to people familiar with the situation. The price of a small rough diamond, the type that would end up clustered around the solitaire stone in a wedding ring, has surged about 20% since the start of March, the people said.

“Diamonds are not like oil, where some other country can jump in to make up for a shortfall,” Shah said. “No new mines are coming up elsewhere. Our dependence is huge.” Gems and jewelry are India’s third-largest source of export revenue, pulling in about $39 billion for the fiscal year that ended in March.

In Manhattan’s diamond district, where salesmen corral tourists outside dozens of neon-lit stores, dealers said business has stalled over the past few months. The war is the latest blow to a market beleaguered by supply chain woes, slowing mine production and rising inflation.

Avi Davidoff, a consultant at Leon Diamond, said customers are now asking if stones are coming from Russia — though interest is still more muted than after the release of the Hollywood movie “Blood Diamonds,” which centers on ones mined in African conflict zones.

“The cherry on top is no one knows where this war is going,” he said.

Sanctions from the US have caused friction in New Delhi. While much of the West remains united against Russian aggression, India, which considers Moscow a close political and trade ally, continues to import oil, weapons and commodities. That has provoked irritation — and sometimes out-right fury — from NATO allies and Washington power-brokers. They see Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s subtler approach to Russia as a betrayal of a fellow democracy.

The quagmire facing India is one shared by many nations with long-standing ties to Russia: In a hyper-globalized economy, how do you placate sparring allies while also protecting domestic growth?

It’s a riddle with no clear answers. India is the world’s largest buyer of Russian weapons, though the overall trade relationship is fairly limited. Officials are mulling ways to continue doing business after the US and European Union blocked Russia from SWIFT, the Belgium-based cross-border payment system operator. One approach involves Russia depositing rubles into Indian banks, where they would then be converted into rupees.

A delegation from Alrosa visited India last month and met customers and trade groups to discuss selling diamonds using that workaround, people familiar with the matter said. But talks were inconclusive, the people said, and officials remain sensitive to provoking the US, which sees India as a regional check on China’s power. Alrosa declined to comment.

Amitendu Palit, a senior research fellow in South Asian studies at the National University of Singapore, said India faces a “tough, complicated balancing act” in managing “pro-Russia and pro-rest of the world stances.” American commerce secretary Gina Raimondo has likened a ruble-rupee arrangement to “funding and fueling and aiding President Putin’s war.”

“Challenges are likely to increase if the conflict continues for a long time,” Palit said. “There will be tacit pressure on India to shift away from Russia for its trade.”

With no longer-term solution in place, traders are getting nervous in Surat, an industrial hub in Modi’s home state of Gujarat.

The city houses about 5,000 polishing units, ranging from those that employ hundreds of workers to ones with just a handful of people. In Mahidharpura, the biggest bazaar, traders use tweezers and magnifying glasses to inspect thousands of gemstones bound for Western jewelers. There are so many polishers that some spread cotton sheets on the streets and do their work outside.

Factories are bubbles of calm. Often the only sound is the hum of a radio playing the Ramayana, an ancient Hindu epic. At B. Virani & Co., which supplies to clients such as Tiffany, employees work 10-hour shifts at a turntable-like machine that cuts diamonds. Salaries hover around $450 a month.

On a recent visit, traders said they were working on borrowed time. Smaller factories, some of which have been in operation for decades, would be the first to go should sanctions persist. Several units have already started reducing working hours. The messy logistics of separating Russian stones — which are typically no bigger than a few millimeters — from ones mined in places like Africa or Canada could derail the industry, which employs about a million people in Surat.

Abhishek Baid, a third-generation trader, said it’s a prospect that worries everybody.

“A trained eye may be able to differentiate diamonds of varying origins due to the color, but to do this on a larger scale will be impossible,” he said.

(By Swansy Afonso, with assistance from Shruti Srivastava, Joe Deaux and Thomas Biesheuvel)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments