Gangs stealing cables miles underground torment South African platinum mines

South African miners are battling a growing threat miles underground in the world’s deepest platinum shafts: Gangs stealing copper cables and disrupting operations.

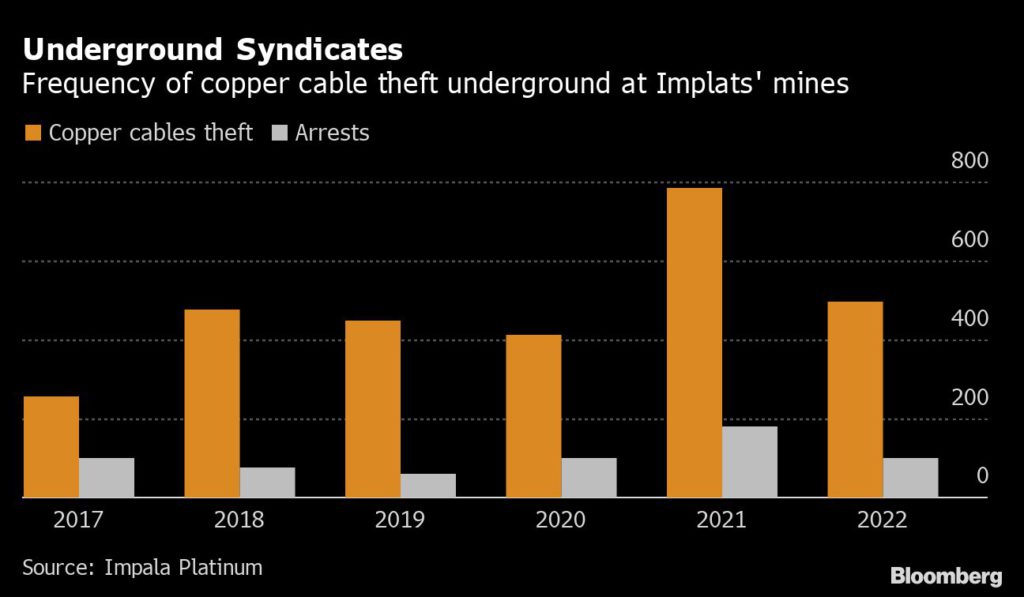

Enticed by high copper prices, thieves are sneaking in, descending deep underground and setting up camp among vast networks of tunnels to strip metal from power cables. The country’s platinum giants are struggling to contain the syndicates of trespassers known as “zama zamas” — a Zulu name that means “take a chance.”

Illegal mining has long been a problem in South Africa, though now thefts of equipment are becoming a major worry. The incidents — in some cases daily — can halt work for about a week at a time as cable cuts cripple systems such as locomotives that take ore to the surface.

The looting is part of a crime wave affecting vital infrastructure from railways to telecommunications to utilities, undermining President Cyril Ramaphosa’s efforts to revive the economy. The thefts have become increasingly lucrative with copper recently hitting a record high on expectations that supply will remain tight and mining companies finding it hard to keep the gangs out.

It’s a fresh headache for companies like Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd., Sibanye Stillwater Ltd. and Anglo American Platinum Ltd. They’re the largest producers in South Africa, the top miner of platinum-group metals and the location for the African Mining Indaba that starts Monday, a huge gathering for the industry.

Zama zamas, who have plagued gold deposits for many years, sell stolen metal for scrap or even export it.

“Every single day there is at least one place that’s not working because of cable theft,” said Mark Munroe, head of Implats’s Rustenburg complex. “At our most marginal shafts, if cable theft is not stopped, we may be forced to shut mining operations because these marginal shafts will not be able to sustain themselves under these conditions.”

The thefts are difficult to stop because it’s impossible to fully patrol all the tunnels that cover a vast distance. What started as informal ventures have become so organized that gangs now have their own supply chains to keep groups underground for longer. Workers have even smelled thieves’ food.

Gangs use ropes or handmade ladders to lower themselves down from holes dug on the surface. After the treacherous descent, stripped copper is then hidden in unused tunnels before being taken away at night using pre-arranged transport. Big cables are typically cut into smaller pieces to be carried out.

Roughly 500 people are illegally underground for as long as 60 days at any time at the sprawling Rustenburg site, Munroe said. It takes at least a week to reinstall some key copper cables and if the issue isn’t contained.

“These guys are well trained, they work with intelligence, they know where to go underground,” he said.

The vandalism is dangerous too. When copper was stripped at Sibanye’s Thembelani shaft in March, it caused a fire that quickly spread and forced the evacuation of 140 workers. About 10 were treated for smoke inhalation.

The company had 120 theft incidents last year and recovered about 5.1 tons of stolen copper. So far this year, there have been 45 incidents and 3.2 tons recovered, with operations disrupted twice, according to Sibanye, which has stepped up security.

The interruptions threaten to crimp output of platinum metals that are mainly used in autocatalysts that cut vehicle emissions. While the platinum sector is reaping windfall profits again on the back of historically high palladium and rhodium prices, it had until a few years ago long suffered from rising costs and low metals prices that made running aging mines harder.

Thefts aren’t the only problem. Record unemployment and the world’s most unequal society — the richest 10% of the population own more than 85% of household wealth — are fueling unrest around mines from people frustrated at government failures to provide basic services such as clean water.

Communities want producers making big profits to tackle social challenges, and every other week Implats’s operations face protests for jobs, water and education, Munroe said. Losses could reach 15 million rands ($958,000) a day at a shaft if protesters block roads and prevent worker access, he said.

Some unrest is also created by local contractors trying to win more work, by indicating to mining companies that they can ease protests if they’re hired, Sibanye spokesman James Wellsted said.

Tackling theft

To discourage thefts, the government is trying to combat the illegal trade in cables through measures such as requiring metal traders to get licenses and preventing them from using cash. Some syndicates use bulk buyers to handle metal stripped from mines, according to Implats.

That shows just how complex the criminal ventures are.

“The tunnel workings and exit points also show you the levels of planning and sophistication is much higher than one guy making a hole to be in and out,” Implats’s Munroe said. “It takes a lot to maintain this system.”

(By Felix Njini, with assistance from Tom Hall)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments