Future copper supply imperiled by project freeze at top producer

The pandemic is raising questions over the biggest copper producer’s ability to maintain output levels in the coming years and satisfy growing global demand.

Like many of its private-sector peers, state-owned Codelco has largely given up on project development for the time being to focus on running existing mines with reduced staff. For the Chilean behemoth, though, the consequences of prolonged building delays would be far greater.

Decades of underinvestment mean Codelco is having to spend more than $40 billion over the next decade just to maintain production

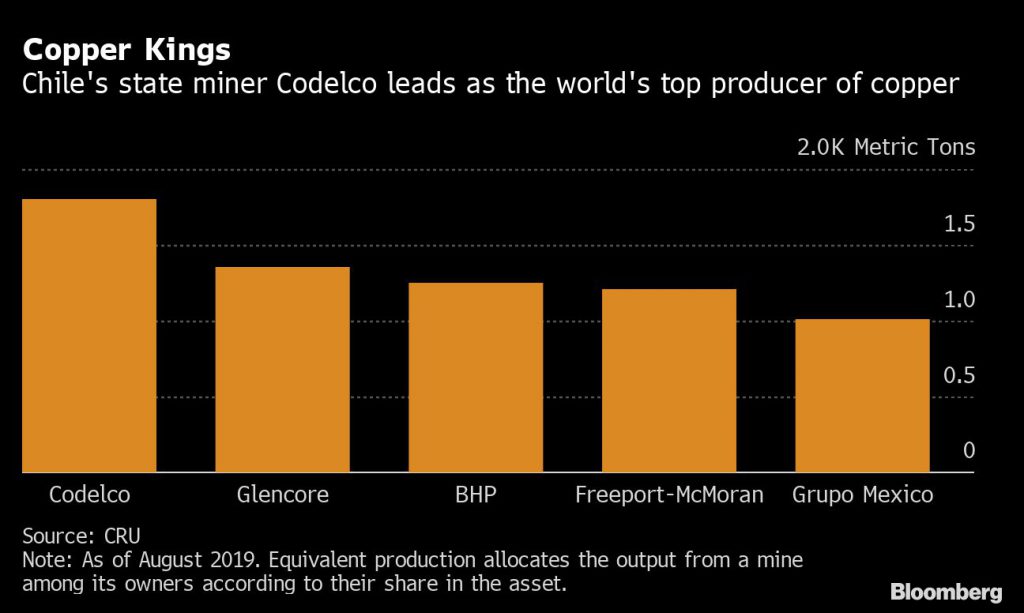

Decades of underinvestment mean Codelco is having to spend more than $40 billion over the next decade just to maintain production. Without those projects, the company’s output would tumble, dethroning it as the top producer, reducing global supply by about 2% and potentially sending what’s thought to be a fairly balanced market into deficit.

To be sure, development work will resume eventually and in some cases is already well advanced. Other suppliers could also pick up some of the slack. But investors may be underestimating the risk of delays to projects that are key to meeting future demand in an electrification trend, said Bloomberg Intelligence senior analyst Andrew Cosgrove.

“It is one of the more under-appreciated risks out there,” Cosgrove said. “Everybody takes for granted that production at Codelco will be able to be kept flat.”

In an effort to contain the spread of the virus, Codelco has halted work to convert its Chuquicamata open pit into a underground mine, as well as a major project at its largest and most profitable mine, El Teniente. Private-sector operators have also stalled projects, including at mines owned by Teck Resources Ltd. and Antofagasta Plc.

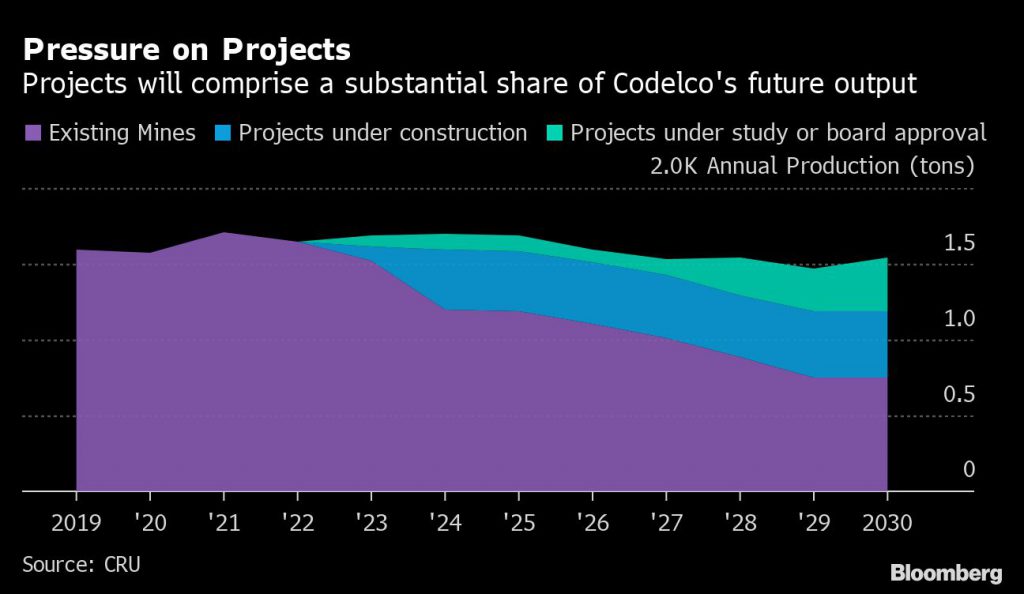

Codelco’s so-called structural projects are set to contribute more than half of its output by the end of the decade, according to CRU Group. If it doesn’t upgrade assets, it risks an output decline of 600,000 tons, CRU estimates. That’s enough to wire more than 7 million electric cars.

In the case of El Teniente, which accounts for almost a third of Codelco’s output, “any considerable delay in the construction could impact copper production from 2022 onwards,” said CRU analyst Jaime Sepulveda.

Chilean output forecasts for 2022 through 2024 could be rattled by project delays, government agency Cochilco said in an emailed response to questions. Santiago-based Codelco declined to comment.

For Codelco, the ripples of project delays go beyond future revenue. Ore quality is falling at its aging deposits, meaning more volume has to be processed to produce the same amount of metal at a higher cost.

That means less profit and potentially a greater need to tap debt markets, which in turn signals higher credit costs. Debt is already at record-high levels. For the Chilean state, Codelco’s owner, it also means less income at a time when social demands are pushing up public spending.

Copper’s surge back to the highest price in more than a year eases some of those pressures and the long-term demand outlook for the metal used in wiring is strong.

“It’s not like they’re going to get into severe financial distress, but it just makes it more challenging for them to balance the books in terms of project spending,” said BMO Capital Markets analyst Colin Hamilton.

In November, Chief Executive Officer Octavio Araneda slashed Codelco’s project budget through 2028 by $8 billion, placing the future of the Andina, Radomiro Tomic and Salvador expansion projects in the balance.

Some of those projects, which were due to be commissioned in the late 2020s to early 2030s, probably will be postponed indefinitely, and could result in a loss of 500,000 tons of copper, said BMO’s Hamilton.

“I do think there’s a risk we’re going to be downgrading the supply forecast over the coming years,” he said.

(By Jackie Davalos)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments