Fusion is nuclear power without the meltdowns and radioactive waste

Abundant fuel. No danger of a meltdown. No lingering radioactive waste.

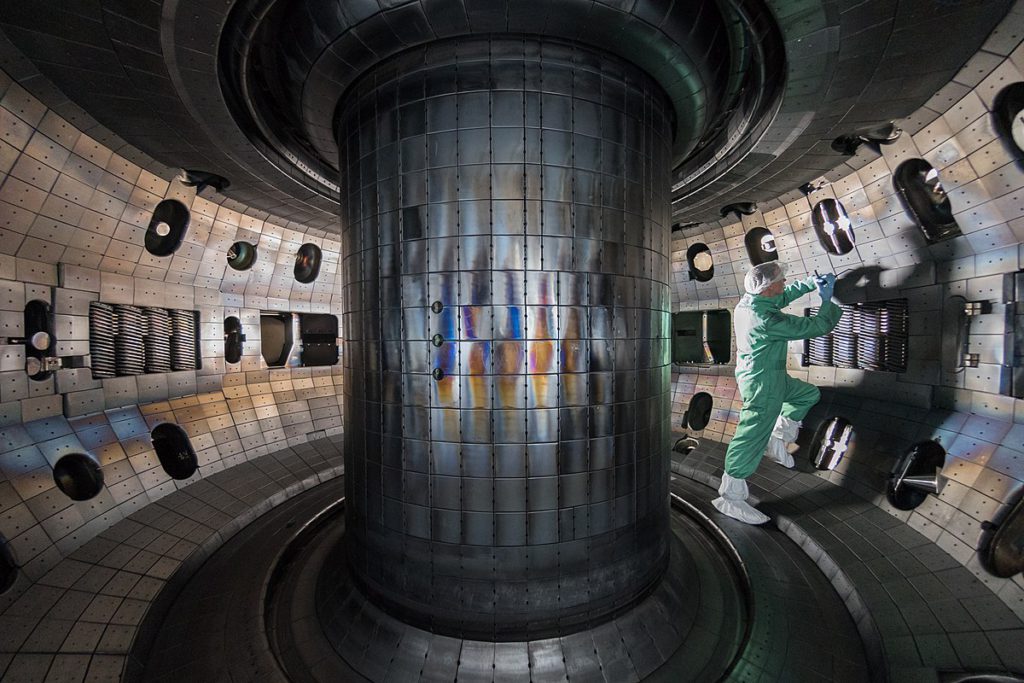

Nuclear fusion, the process US researchers successfully demonstrated this month, has big potential advantages over the nuclear power plants operating today, which run on an entirely different principle. If perfected into a form that can run in a power plant — not just an advanced government lab — fusion could offer a clean power source that avoids many of the pitfalls that have dogged nuclear energy for decades.

All existing nuclear plants use fission — splitting atoms apart — rather than fusion, which involves fusing them together. Fission plants are fueled by uranium pellets that are crammed inside long metal rods. The uranium must be mined and refined, and after its use, it stays radioactive for thousands of years. Unless it’s reprocessed, that waste must be carefully stored and monitored, decade after decade.

Fusion, however, uses as its fuel two isotopes of hydrogen, the universe’s most abundant element. One of the isotopes, deuterium, is readily available in seawater. The other, tritium, can be made by exposing lithium — the same metal used in batteries — to neutrons. Fusion merges those two hydrogen isotopes into helium, with no long-lived waste. Neutrons from the reaction will, over time, render the reactor materials themselves radioactive, but with a far shorter half-life than the waste from a fission plant.

Advocates say the types of fusion reactors under development today also couldn’t melt down, the type of catastrophic accident that befell the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in 2011. Achieving ignition within the reactors takes an enormous amount of energy, so if something disturbs the process, it simply stops, rather than continuing in a runaway reaction.

But that points to one of the reasons commercial fusion power may still be decades away, if it arrives at all. The breakthrough the US Department of Energy announced Tuesday involved the momentary ignition of a single fuel capsule — not something than can run a power plant.

“There are very significant hurdles, not just in the science but the technology,” said Kimberly Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where the milestone was achieved. “This is one igniting capsule, one time.”

(By David R. Baker)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments