Fossil-free energy supply gives Sweden edge in green steel race

As European steelmakers try to revolutionize the dirty production processes that have turned them into one of the main culprits behind the climate crisis, one producer may have an edge over its rivals.

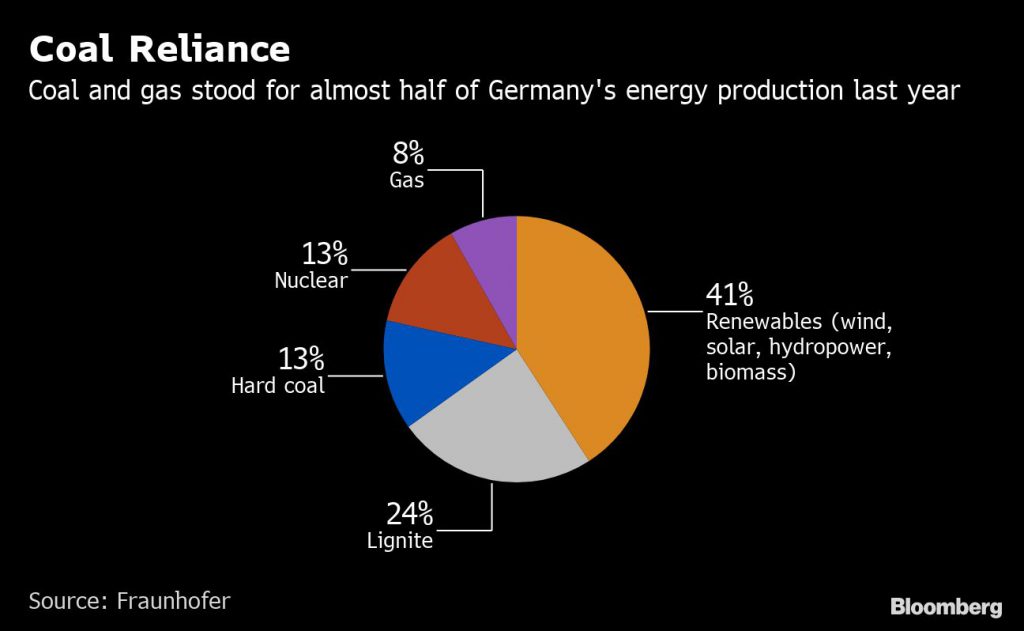

Sweden’s SSAB is just like European rivals such as Thyssenkrupp AG and ArcelorMittal turning to hydrogen as a replacement for coal in its processes to cut emissions of carbon dioxide. But to really become green, the steelmakers must ensure that the electricity used to extract hydrogen is also free of fossil fuels, which is a problem for German steelmakers as the country still relies heavily on coal and natural gas for its power needs. Sweden’s energy supply, in contrast, is almost entirely built on non-fossil energy sources.

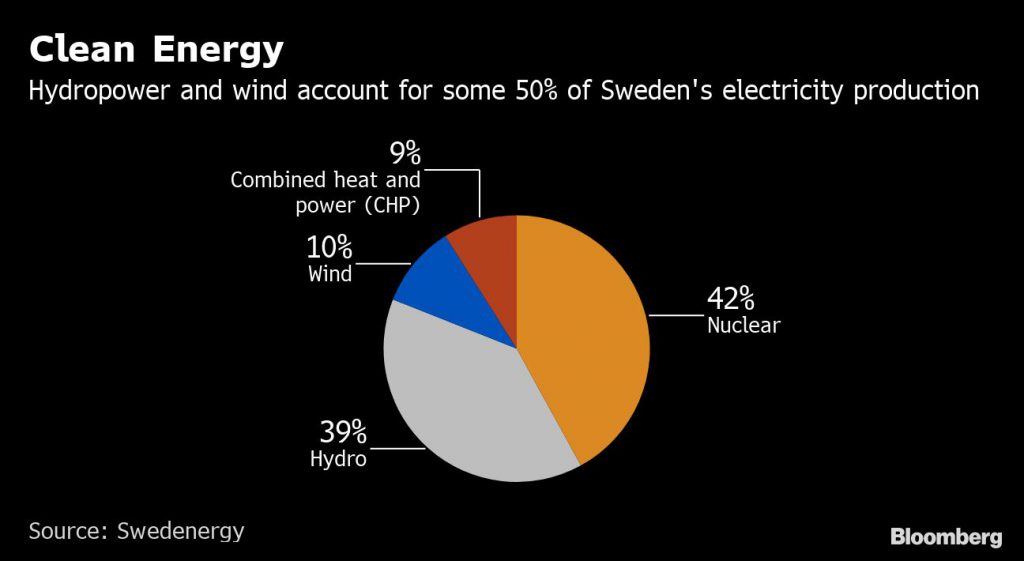

Hydropower accounts for some 40% of the Nordic nation’s energy production, with nuclear making up another 40% and wind accounting for about 10%. That gives SSAB, which together with utility Vattenfall and iron-ore miner LKAB is exploring a move to hydrogen in a project called Hybrit, a headstart.

“The base in hydropower is favorable and gives Sweden an advantage when it comes to projects such as Hybrit,” Ola Sodermark, an industry analyst at Kepler Cheuvreux, said by phone.

The stakes could be high as customers seek to lower their own carbon footprint by evaluating their entire supply chain. As the car industry switches to electrical vehicles, it’s likely to be interested in paying a premium for carbon-neutral materials and use them as a sales pitch, Sodermark said.

In Germany, hard coal, lignite and natural gas accounted for almost half of the power production last year. The Ruhr industrial region, Germany’s steel-making heartland, doesn’t have much wind or solar generation potential and steelmakers are now betting on utilities such as Uniper SE or RWE AG to supply them with hydrogen extracted using wind energy from the North Sea.

There has been skepticism over whether the cash-strapped steel industry can afford the fundamental change that a shift away from coal to hydrogen entails, as it would require massive investment and almost inevitably higher steel prices and for many steelmakers, a new stream of renewable energy.

But SSAB, which already has access to a lot of renewable energy and has come further than many of its peers, is serious. With global steel consumption set to grow and increased pressure on the industry to tackle emissions, “we need to take a big leap technologically if we want to solve the demand issue and at the same time reduce our carbon dioxide footprint,” Martin Pei, SSAB’s chief technology officer and the initiator of the Hybrit project, said.

If SSAB, Vattenfall and LKAB are successful with Hybrit, the company aims to produce steel through a fossil-free process by 2035. As SSAB is one of the biggest emitters of carbon dioxide in Sweden, success could reduce Sweden’s CO2 footprint by 10% and Finland’s by 7%.

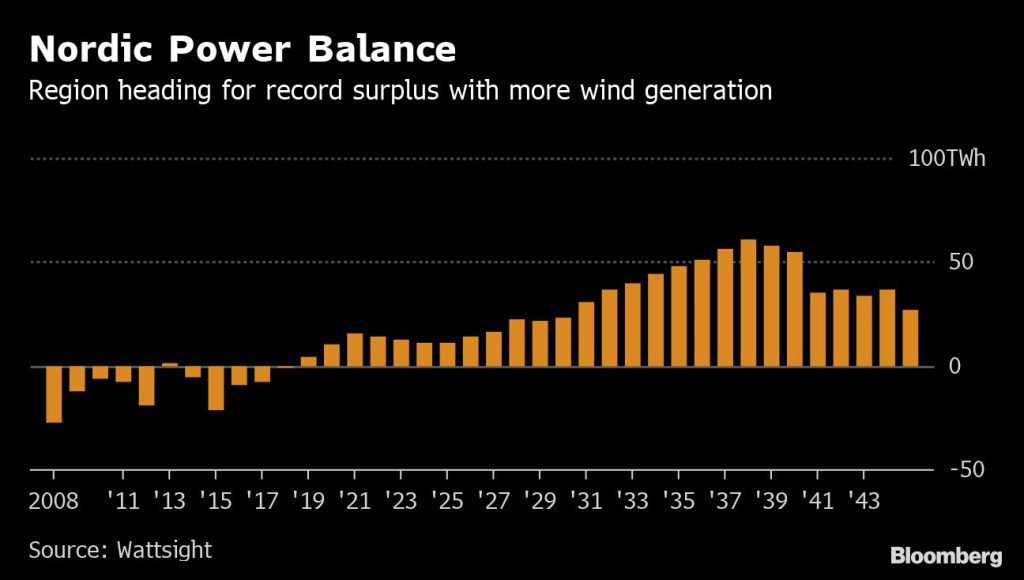

But there are challenges also for SSAB. The company’s estimated need for electricity would amount to somewhere around 10% of today’s total consumption in Sweden, should it convert completely to using hydrogen instead of coal. That could be troublesome in Sweden, which has excess power supply but significant bottlenecks in its grids.

(By Hanna Hoikkala and Jesper Starn)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments