Fertilizer turmoil bolsters Brazil’s case for mining the Amazon

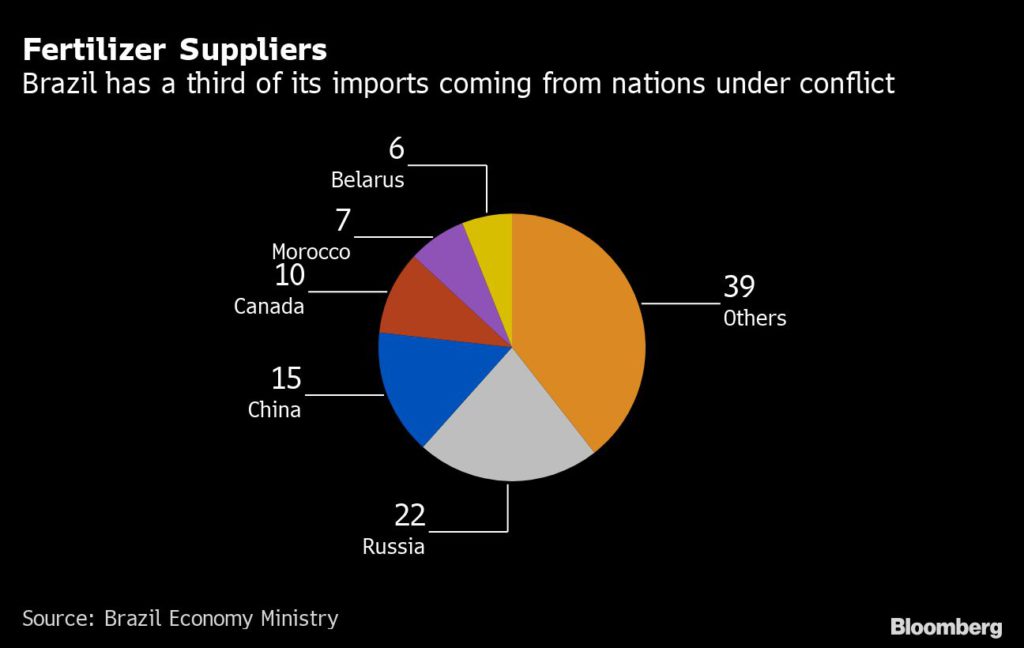

The ripples of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may reach all the way to Amazonian rainforests as Brazil sees disruptions to global fertilizer supplies as another reason to produce more of its own.

Insufficient domestic supplies of crop nutrients have been a thorn in the side of Brazil for decades, with the agricultural superpower importing about 80% of its needs. The Ukraine war has seen Brazilian farmers struggle to buy fertilizer, fueling a debate on the exploitation of potash reserves in the Amazon, including on indigenous lands.

President Jair Bolsonaro came out this week in support of boosting domestic supplies of potassium-based nutrients as part of his push to open up the biome to development. Industry groups followed suit as global turmoil exposes the fragility of supply chains. The debate pits the need to feed the world against protecting the most bio-diverse place on the planet.

“With the Russia/Ukraine war, we are at risk of facing a lack of potash or its price increase,” Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro wrote on his twitter account. “Our food security and the agribusiness (economy) require from us, Executive and lawmakers, measures that allow the non-foreign dependency of something we have in abundance.”

Bolsonaro urged lawmakers to push through a controversial bill that would allow mining on indigenous territories. His comments were slammed by indigenous groups, who say the government proposal threatens the health and rights of communities. A recent government decree to support artisanal mining was criticized by environmentalists as encouraging illegal activities that imperil rainforests.

The potential of potash production in the Amazon Basin is similar to the Urals region, in Russia, and Saskatchewan, in Canada, according to the state geological survey of Brazil known as CPRM.

Deposits held by Petrobras and Potassio do Brasil, a company controlled by Canada’s Forbes & Manhattan, have a combined 3.2 billion metric tons of resources. Other analyzed areas could double that.

“We can’t abandon potash exploitation in the Amazon,” CPRM director Marcio Remedio said. “It is strategic in terms of economic growth, inflation (control) and food security.”

Potassio do Brasil’s project and two other phosphate initiatives have qualified for a government program to speed up strategic mining projects. Now mining companies represented by industry group Ibram want the government to create a working group involving Potassio do Brasil to seek the advancement of its potash project in Autazes, in Amazonas state, as Black Sea tensions boost the risk of fertilizer shortages.

Farmers are also on board.

“These times are making us discuss the need to extract potash in Brazil. We have big reserves, but unfortunately they are in indigenous lands,” said Bartolomeu Braz Pereira, head of Brazil’s largest farming group Aprosoja. “We can’t rely in other nations for fertilizer supplies.”

For Greenpeace, the government’s attempt to accelerate the vote on the Amazon mining bill shows its disrespect toward indigenous rights and inability to tackle the situation.

“Bolsonaro’s government lies while it suggests that approving the bill could solve an eventual fertilizer shortage as it omits that solutions for this kind of problem require mid- and long-term planning,” said Danicley de Aguiar, a spokesman for Greenpeace Brazil.

The Canadian miner took the first steps in the project in 2008. It obtained a preliminary license that was later suspended by a Federal Court that required prior consultation with the Mura indigenous people, it told Bloomberg. The $2.3 billion project should be ready in about five years, with annual potassium chloride production envisaged at 2.4 million tons.

Even if the country green-lights mining on indigenous land, opening a potash mine in the Amazon brings challenges such as energy supply and the technology to drill down as deep as a kilometer.

“A licensing process of this size takes at least three to five years, so it won’t solve the crisis,” said Suzi Huff, a geologist and professor at Brasilia University.

Despite the obstacles, Brazil is processing 535 requests for potash exploration rights, although not all those are in the Amazon. That’s a 49% increase from the end of 2020.

(By Mariana Durao and Tatiana Freitas)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments