Explainer: Why does Norway want to mine the seabed?

Norway may become the first country to start commercial deep sea mining, if parliament approves a government proposal to open an offshore area larger than the United Kingdom, despite international calls for a global moratorium.

Parliament is set to discuss the government’s bill this autumn.

Why does Norway want to extract seabed minerals?

The government says deep sea mining could help Europe reduce its dependence on China for the supply of critical minerals needed to build electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines and solar panels.

It’s also a part of Norway’s strategy to develop new maritime industries as its top export, oil and gas from offshore, is expected to decline gradually.

What does the government propose?

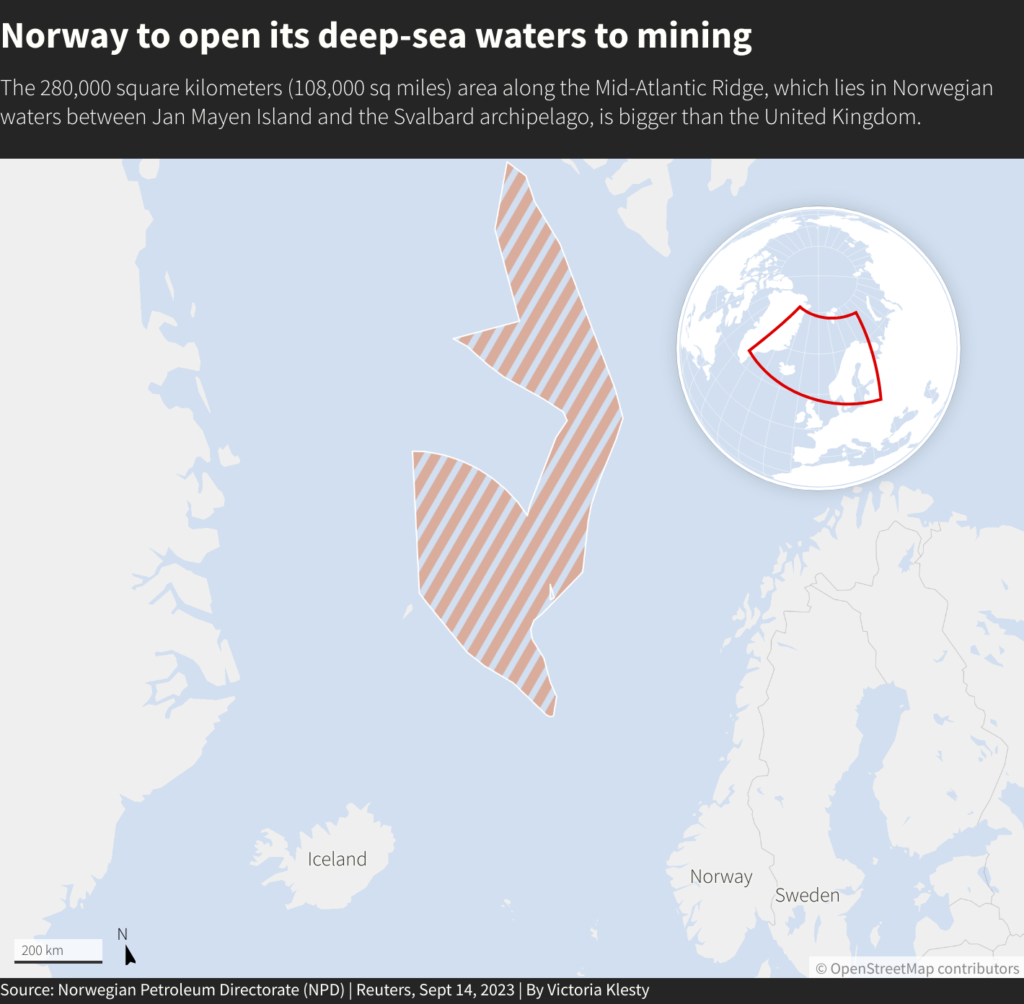

The Labour-led minority government has proposed to open about 280,000 square km (108,000 square miles) of ocean areas between Jan Mayen island and the Svalbard archipelago.

Its proposed plan follows similar principles to the opening of offshore areas to oil and gas exploration. From the overall area on offer, smaller zones, or blocks, would be offered to companies to explore and produce from.

While international rules for seabed mineral extraction are yet to be set, Norway doesn’t need to wait, because it plans to explore for minerals on its extended continental shelf.

What minerals does Norway want to extract from the seabed?

A government-sponsored survey found “substantial” amounts of metals and minerals, ranging from copper to rare earth elements.

Those minerals were found in polymetallic sulphides, or so-called “black smokers”, some 3,000 metres (9,842 feet) deep. It’s where seawater contacts magma coming up through the surface through tectonic cracks and then is flushed back carrying dissolved metals and sulphur.

Rare earth elements, such as scandium, were also found in manganese crusts which grow on bedrock at a speed of one centimetre (0.4 inch) per million years. Norwegian surveys have proven crust deposits with thicknesses of up to 40 centimetres.

Is there life at the bottom of the seabed?

In depths of over 1,000 metres (0.62 miles), there is no light, temperatures are near freezing and the water pressure is high.

Life does, however, exist and scientists have found unique species living around active hydrothermal vents, such as corals, tube worms and microorganisms. Little is known about how these ecosystems work.

What risks are there to the environment?

A government-commissioned impact study said the impact would be of a local nature, limited to the actual area being extracted. It also said the impact on fisheries would be minimal.

Companies say they plan to extract minerals from inactive hydrothermal vents, where biodiversity is less abundant, but some scientists say they are concerned the practice could destroy the species even before they are discovered.

The government’s proposal has been criticised by some green groups, such as the World Wildlife Fund, but also by its own environmental agency, which said the gaps of knowledge about deep sea biology were too big to decide on the opening.

What do other countries say?

Denmark said Norway’s environmental study for the area opening was not good enough, while Iceland has questioned Norway’s exclusive rights to explore for seabed minerals near the Arctic Svalbard archipelago.

Norway is not part of the EU but is a member of the European single market. The EU’s views on the issue are vital for Oslo’s plans, some analysts have said.

Norway is encouraged by EU ambitions to diversify imports of critical minerals and to boost local production.

However, the European Parliament has also called on member-states to support a global moratorium on seabed mining. The European Commission has been also advocating for a deep-sea mining moratorium until more is known about the risks.

How do you mine minerals from the seabed?

There is no commercially available technology to produce seabed minerals, though some machines have been built to test production elsewhere in the world.

Researchers in Norway used undersea robots and drilling machines to collect mineral samples at the ocean floor.

Extraction of minerals from the seabed in Norway would likely involve cutting and crushing the rocks before bringing those to surface.

Some Norwegian companies that provide technology and services to the oil industry are looking at deep sea mining as well.

(By Victoria Klesty and Nerijus Adomaitis; Editing by Gwladys Fouche and Timothy Gardner)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Greg Abramov

Why don’t we utilize borehole mining to go BEYOND the seabed? It would leave the seabed undisturbed and open vast amounts of natural resources hundreds of meters below it.