Europe’s other energy problem: relying on Russian nuclear fuel

A day before Russia invaded Ukraine, it sent four highly-trained armed guards across the border on a special mission to deliver fuel to an aging nuclear power facility.

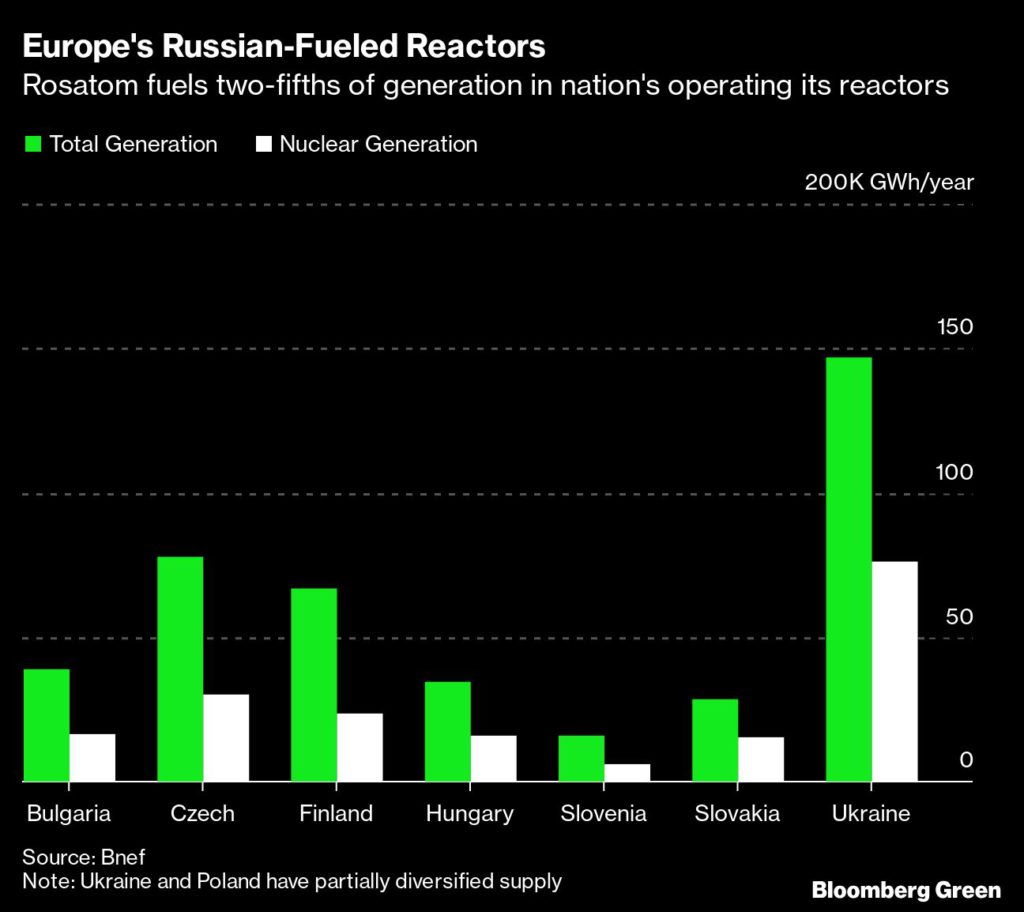

Reactors based on Soviet designs generate power across the former Cold War bloc, accounting for more than half of all electricity in Ukraine and around two-fifths in a swath of territory arching from Finland to Bulgaria. So the fuel shipment was routine enough — until President Vladimir Putin ordered his army to war.

Russia and Ukraine agree the small security detachment arrived by train on Feb. 23 and was present as technicians unloaded a new batch of fuel rods at the Rivne Nuclear Power Plant 340 kilometers (210 miles) west of Kyiv. They differ wildly over what happened to the so-called Atomspetstrans guards as fighting began.

Ukraine told the International Atomic Energy Agency last week that they were disarmed and subsequently refused to return home. The Kremlin accused Kyiv of taking the four employees of state-owned Rosatom hostage. The IAEA is assessing the situation as it prepares to return monitors to Ukraine.

The incident was just one nuclear flashpoint of a war that’s being fought amid a fleet of operating reactors as well as the entombed site of the world’s worst atomic accident at Chernobyl.

But it also highlights another looming energy challenge for leaders on Moscow’s European periphery even as the continent moves to bar more Russian fossil fuels: how to cut their reliance on nuclear trade with a heavily-sanctioned Russia that many in the region want to further isolate.

“Countries are taking it a lot more seriously because of the situation,” top U.S. nuclear official Bonnie Jenkins said in an interview last month. “They are aware of their dependence.”

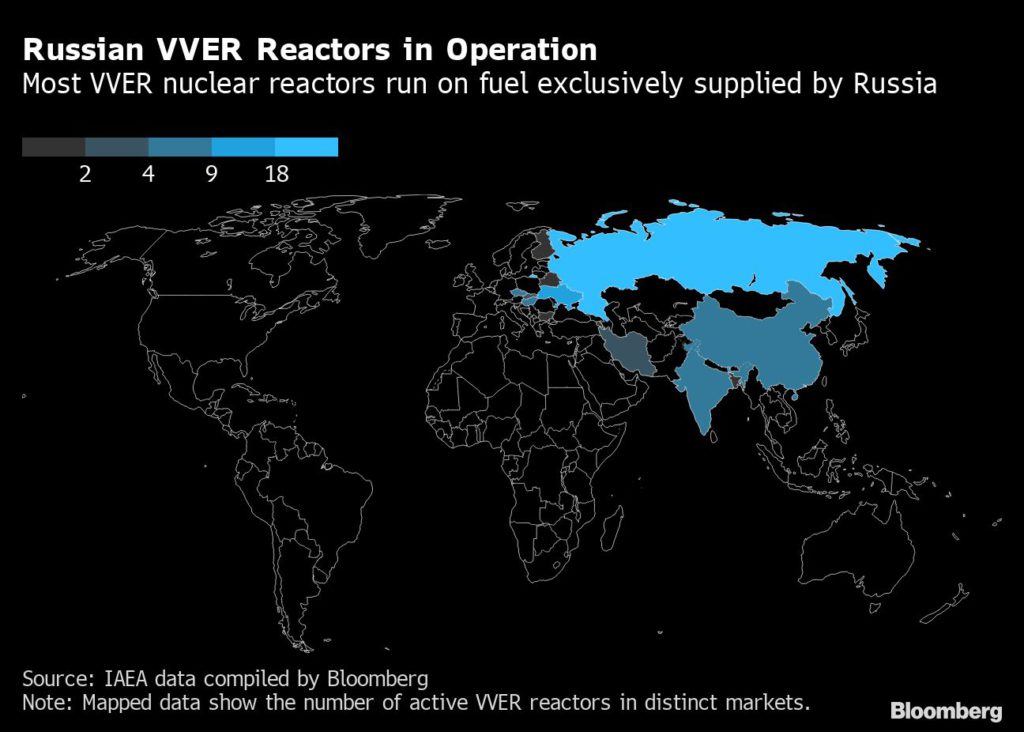

Rosatom, which is the world’s biggest exporter of nuclear reactors and maintains a near-monopoly over the fuel they use to generate electricity, hasn’t been sanctioned by the U.S. and Europe.

Non-proliferation experts have warned that doing so could boomerang back by coaxing more countries to enter fuel markets. U.S. officials said last month sanctions would have to be carefully calibrated to avoid damaging allied economies, as well as other U.S. diplomatic efforts, like the nuclear negotiations with Iran. Those talks foresee continued supply of fuel to the Persian Gulf country’s Russia-built reactor.

For Moscow, atomic exports remain a key geopolitical lever, and it’s using state financing to expand Rosatom’s reach with new units in China, India, Iran and Turkey, none of which have enforced war-penalties so far imposed on Russia.

Nuclear fuel differs from commodities like gas or coal because it requires precision-engineered assemblies that conform to licensing requirements set by safety regulators. Trying to cut ties prematurely with Russia could imperil electricity supplies for almost 100 million Europeans in countries that rely on nuclear plants as their biggest source of clean energy.

Jenkins, 61, the U.S. State Department’s under-secretary for arms control and international security, cautioned the switch could take years.

Still, said Liisa Heikinheimo, deputy director general for energy at Finland’s Economy Ministry, “it’s a fact that an alternative supplier is needed. It’s about to be a problem that’s soon reality.”

Finland, where Fortum Oyj operates two Soviet-built VVER reactors 90 kilometers east of Helsinki, has tried to find alternatives to Russia. It contracted British Nuclear Fuel Ltd., now owned by Westinghouse Electric Co., in the 1990s but ultimately stuck with Rosatom’s competitive prices.

More recently, the U.S. Department of Energy and Ukraine worked with Westinghouse to dislodge Rosatom fuel from 15 operating reactors, which still supply more than half the country’s electricity after six weeks of war wrought billions of dollars in damages to infrastructure.

Fuel made by Westinghouse, owned by private-equity investors at Brookfield Business Partners LP, now generates power at six Ukrainian units, with engineers needing until mid-decade to supply the rest.

“Westinghouse started in Ukraine because of the government-to-government agreement with the U.S.,” said Jose Emeterio Gutierrez, the Spanish nuclear engineer who formerly led the company’s decade-long effort to compete with Rosatom. But nuclear-fuel market peculiarities, along with a Soviet technological legacy, makes diversification difficult, he said.

Few nations possess the vast infrastructure needed to convert and enrich uranium ore into metal, which then has to be engineered into ceramic pellets and inserted into zirconium fuel rods with a safety tolerance measured in millimeters. A catalog of international regulations ensures that material isn’t diverted for weapons.

It takes at least five years for a country to license a new supplier and as long as a decade before it can start receiving tailor-made fuel, said Gutierrez. Fuel licensed in one country can’t automatically be transferred to another because of regulations and differences in reactor designs.

For the operators of Russian-made units in Eastern Europe, many of which are running on borrowed time, it may not be worth spending the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to switch fuel sources.

Rising demand for stable energy supplies, along with the European Union’s green label on nuclear power, could help to speed up the process.

Slovakia, with four Russian-built units, pitched a fuel consortium last month to share costs. The U.S. is also involved, pledging last week to help the Czech Republic diversify fuel for its six Russian-designed reactors.

But moving away from Rosatom will require time, said Heikinheimo, who figures it’ll be “three to four years” before Russian fuel currently being used in Finland needs to be swapped out in full for new assemblies.

(By Jonathan Tirone, Kati Pohjanpalo and Jesper Starn, with assistance from Thomas Hall)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments