Energy emissions stall as rich nations kick their coal habit

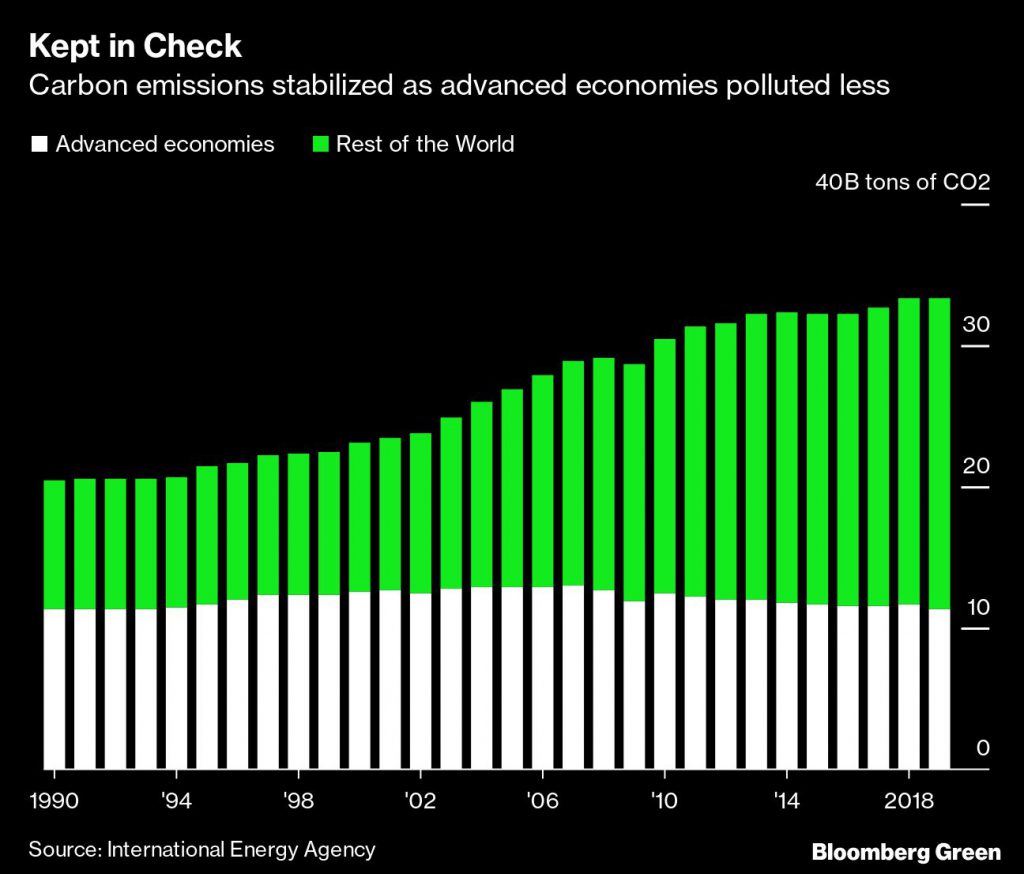

Global emissions from energy held steady in 2019 for the first time in three years. But the restraint all came from the U.S. and Europe as developing countries boosted use of the most polluting fossil fuels.

The findings from the International Energy Agency show energy-related carbon dioxide emissions remained at a record 33.3 billion tons. While industrial countries cut pollution levels to the lowest since 1993, the developing world led by India and China offset those declines.

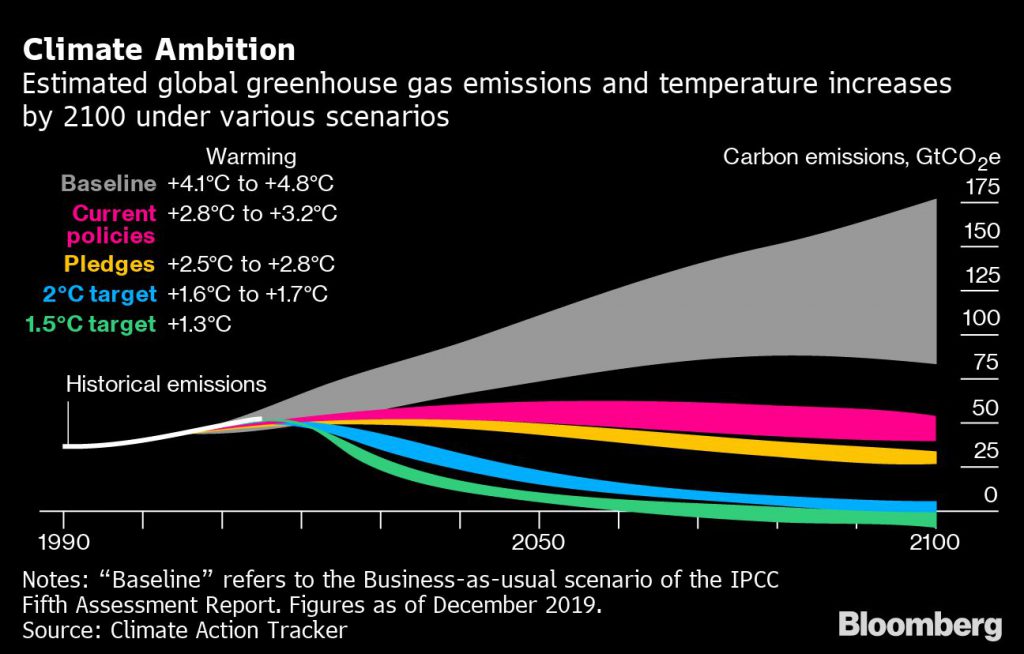

The result leave a glimmer of hope that policy makers can contain the greenhouse gases damaging the atmosphere. That would require China, which is the biggest polluter, and India, whose emissions are growing rapidly, to embrace the economy-wide limits that European countries are adopting. Scientists say increasing heat waves and more violent storms are likely without rapid cuts in greenhouse gases.

“This welcome halt in emissions growth is grounds for optimism that we can tackle the climate challenge this decade,” Fatih Birol, IEA executive director, said in a statement. “We now need to work hard to make sure that 2019 is remembered as a definitive peak in global emissions, not just another pause in growth.”

Burning coal, oil and natural gas accounts for the bulk of the greenhouse-gas pollution. Other activities such as raising livestock and deforestation contribute smaller amounts.

A separate study from the World Meteorological Organization indicated an unprecedented warming of the planet is on the way in the next decade because of building carbon concentrations in the atmosphere. Global temperatures are already consistently breaking records, with 2016 the warmest ever followed by 2019, the United Nations agency said.

The IEA report shows a divergence in policy between industrial and developing nations. While lawmakers are pushing toward a goal to zero out fossil fuel emissions in the EU, Asian nations, especially China and India, are continuing to burn more coal.

U.S. President Donald Trump wants to scrap more environmental limits, but market forces in that nation are pricing out coal as a power generation fuel.

More difficult to control are the emissions given off by catastrophic wildfires seen from the Amazon to Sydney and California. Research showed that the fires that swept Australia have probably doubled the nation’s annual greenhouse-gas emissions, producing as much climate-damaging pollution as all the airplanes in the world.

The emissions being pumped into the air now will linger for decades to come. Global temperatures have already risen about 1 degree Celsius since the start of the industrial revolution, marking the quickest shift in the climate since the last ice age ended some 10,000 years ago. Envoys to the UN’s annual climate talks are looking at how to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the most ambitious target in the Paris Agreement.

Emissions in numbers:

The U.S. reduced emissions by 2.9%, led by a 15% drop in coal power as cheap natural gas eroded its market share and milder weather subdued overall electricity demand.

The EU lowered emissions by 5%, with three quarters of that coming from the power sector increasing renewables and switching from coal to gas. Emissions from Japan fell 4.3%, the most since 2009, as output from recently restarted nuclear reactors climbed.

Despite the stagnation, global emissions still matched a record high set in 2018. Asia accounted for about 80% of the increase from the developing world. Coal demand there remains robust, particularly in Southeast Asia.

China’s emissions rose but were tempered by slowing economic growth and gains in renewable energy and nuclear power. India saw a slight reduction in power-sector emissions that were offset by increases from transport.

(By Dan Murtaugh and Jeremy Hodges, with assistance from Rob Verdonck)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments