Deep-sea minerals could meet the demands of battery supply chains – but should they?

The world is hungry for resources to power the green transition. As we increasingly look to solar, wind, geothermal and move towards decarbonization, consumption of minerals such as cobalt, lithium and copper, which underpin them, is set to grow markedly.

One study by the World Bank estimates that to meet this demand, cobalt production will need to grow by 450% from 2018 to 2050, in pursuit of keeping global average temperature rises below 2°C.

The mining of any material can give rise to complex environmental and social impacts. Cobalt, however, has attracted particular attention in recent years over concerns of unsafe working conditions and labour rights abuses associated with its production.

Concerned scientists have highlighted our limited knowledge of the deep-sea and its ecosystems

New battery technologies are under development with reduced or zero cobalt content, but it is not yet determined how fast and by how much these technologies and circular economy innovations can decrease overall cobalt demand.

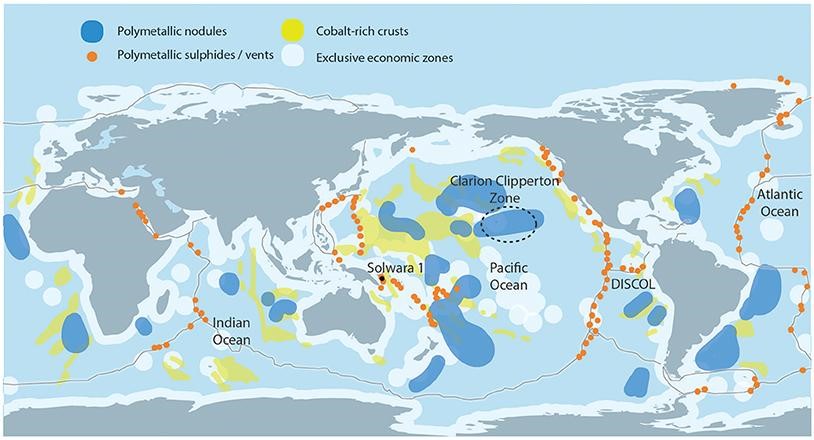

Deep-sea mining has the potential to supply cobalt and other metals free from association with such social strife, and can reduce the raw material cost and carbon footprint of much-needed green technologies.

On the other hand, concerned scientists have highlighted our limited knowledge of the deep-sea and its ecosystems. The potential impact of mining on deep-sea biodiversity, deep-sea habitats and fisheries are still being studied, and some experts have questioned the idea that environmental impacts of mining in the deep-sea can be mitigated in the same way as those on land.

In the face of this uncertainty, the European Parliament, the prime ministers of Fiji, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and more than 80 organizations have called for a 10-year moratorium on deep-sea mining, until its potential impacts and their management methods are further investigated.

A stark choice is fast approaching

The world is facing a stark choice, whether to press ahead with mining the ocean’s floors, hoping that the benefits will outweigh the as-yet-unknown environmental costs, or whether to pause for research and better understanding of what’s at stake.

The International Seabed Authority was established to organize, regulate and control mining on the ocean floor beyond national boundaries. Its regulations determine environmental regulations, financial payment regime for benefit sharing and other standards and guidelines.

The International Seabed Authority has already drafted exploitation regulations for deep-sea minerals, which will be decided upon at either its October 2020 assembly or its 2021 assembly. Once regulations are finalized and adopted by member states, seabed exploitation contracts could be issued for mining to begin.

In parallel, countries that have mineral deposits in their exclusive economic zones, where the country has the unique right to use the marine resources, are also exploring mining techniques and forming their own regulations. Japan successfully trialled extraction of minerals from the deep-seabed as early as 2017, with the aim to reduce reliance on mineral imports. Cook Islands is also considering granting prospecting licenses in 2021 to diversify its economy from tourism.

Governments and seabed mining companies have been exploring mineral content, measuring deep-sea environmental data and testing seabed extracting technologies for more than 30 years.

Manufacturing companies cannot afford to wait

Automotive, electronics, battery, aviation and energy development companies have largely been silent in the deep-sea mining debate, up to now. But deep-sea mined cobalt could enter their supply chains within a decade.

As was demonstrated to Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell and Tesla in 2019, the ethical dimensions of companies’ raw material sourcing choices can have both reputational and legal consequences. That year, a federal class action lawsuit was brought against the five companies, over their alleged use of cobalt produced through child labour in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The ethical dimensions of deep-sea cobalt mining have the potential to be just as contentious, and could pose no less a legal and reputational risk for manufacturers.

Meanwhile, automotive and electronics manufacturers are increasingly acknowledging the strategic importance of their cobalt sourcing decisions.

BMW, Tesla, Samsung SDI, SK Innovation have begun bypassing their suppliers of manufactured parts to sign direct sourcing contracts with mining companies that are traditionally many supply chain tiers removed from their procurement departments. For these manufacturers, access to a stable, ethical supply of cobalt is more important than ever. As they increasingly source metals directly, the need to be knowledgeable on environmental and social considerations of their various supply options also grows greater.

Manufacturers that do not engage in the deep-sea mining debate now risk being taken by surprise by its implications in future years.

A rare opportunity

Seabed mineral reserves have been estimated to contain 94,000 tonnes of cobalt across several different regions – about six times current land-based reserves. If responsible exploitation is possible, these new mineral sources have the potential to dramatically catalyse the low-carbon transition. If exploited irresponsibly, we risk incurring adverse and long-lasting impact on the species, habitats and ecosystems gifted to us by the ocean.

A decision on whether and how to forge ahead is upon us. In order to ensure that we rise to the challenge of that decision, and decide wisely, all stakeholders, including the companies that are set to use this ocean-mined material, must be alert to this emerging debate, and engage with it fully.

Those decisions made today on deep-sea mining are likely to have lasting effects on materials supply chains, the global mineral economy, the economies of some countries, the ocean ecosystem and our ability to tackle climate change as we look to the future.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Long

It is an important issue how to protect our blue ocean, preventing from destroying ecosystem of deep sea.