Death of coal financing is exaggerated as China steps up

Moves by some of the world’s biggest banks to end coal financing for the sake of the planet was supposed to create major headaches for companies like Whitehaven Coal Ltd.

Yet there was the Australian miner on a conference call last month announcing the refinancing and extension of a A$1 billion ($650 million) credit line, backed mostly by Chinese and Japanese lenders.

Asian banks and export credit agencies, private-equity firms and the cashflow from coal sales are all keeping the mines operating with ample funding

“Our banking relationships are strong, we are really well supported,” Chief Financial Officer Kevin Ball said. “That might come as a little bit of a surprise to people who aren’t familiar with coal.”

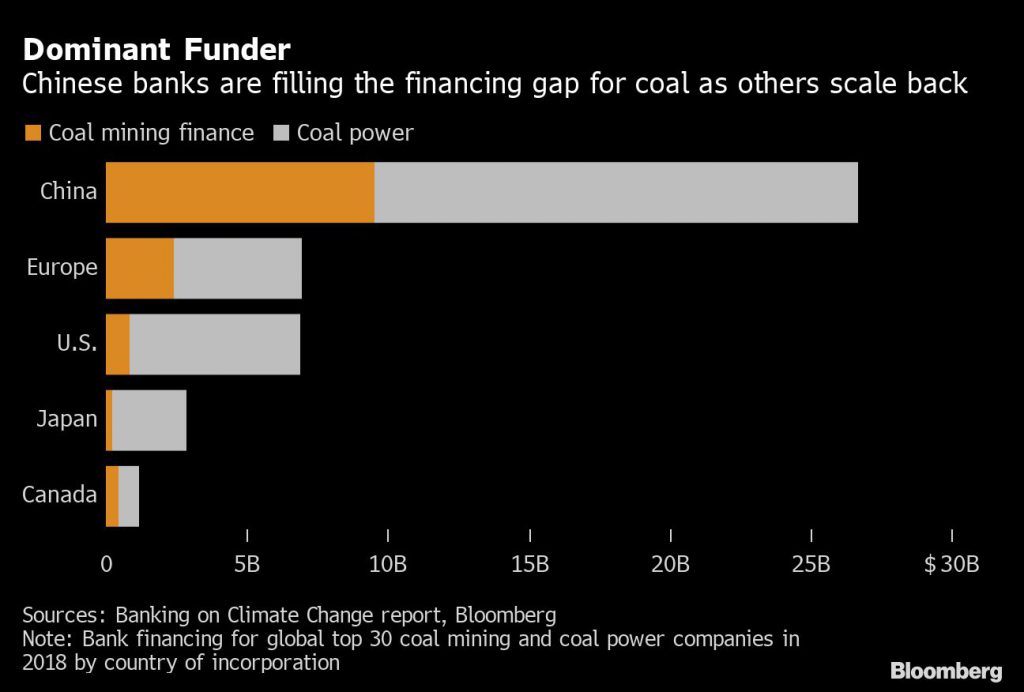

The relatively easy credit underscores the challenge of ridding the world of the dirtiest energy source. While global banks including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and BNP Paribas SA are withdrawing support for coal mines, others are stepping into the breech.

Asian banks and export credit agencies, private-equity firms and the cashflow from coal sales are all keeping the mines operating with ample funding even as pressure mounts to put the industry out of business. The Export-Import Bank of China and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation lead firms that have committed $29 billion for new coal power projects in Vietnam and Indonesia alone.

“If the strategy is to starve coal mines of all debt finance there is still a long way to go,” said Richard Denniss, chief economist at the Australia Institute, an environment-focused think tank.

There are several reasons why money continues to flow into the pariah commodity that’s responsible for 800,000 premature deaths each year, according to campaign group End Coal.

Coal plants

Asian powerhouses China and Japan remain heavily reliant on coal-fired generation for their energy needs. Coal accounts for more than 65% of the power supply in China and 30% in Japan, and still generates more electricity globally than any other fuel.

China saw an increase last year of 2%, resulting in a share of more than half the world’s coal-fired generation for the first time.

Banks from these end-user countries are increasingly coming to Australia to fund resource projects, Whitehaven’s Ball told investors. Bank of China Ltd. and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. are both part of Whitehaven’s loan syndicate, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

In all, Chinese and Japanese banks now hold over 50% of the debt facility at Sydney-based Whitehaven, compared with about 20% six years ago when local lenders dominated. Australia’s biggest lender, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, is no longer part of the group, though Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. remains.

More broadly, Asian banks dominate global funding for coal mines and plants, particularly in countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, which have some of the world’s most aggressive plans to ramp up coal power production over the next decade.

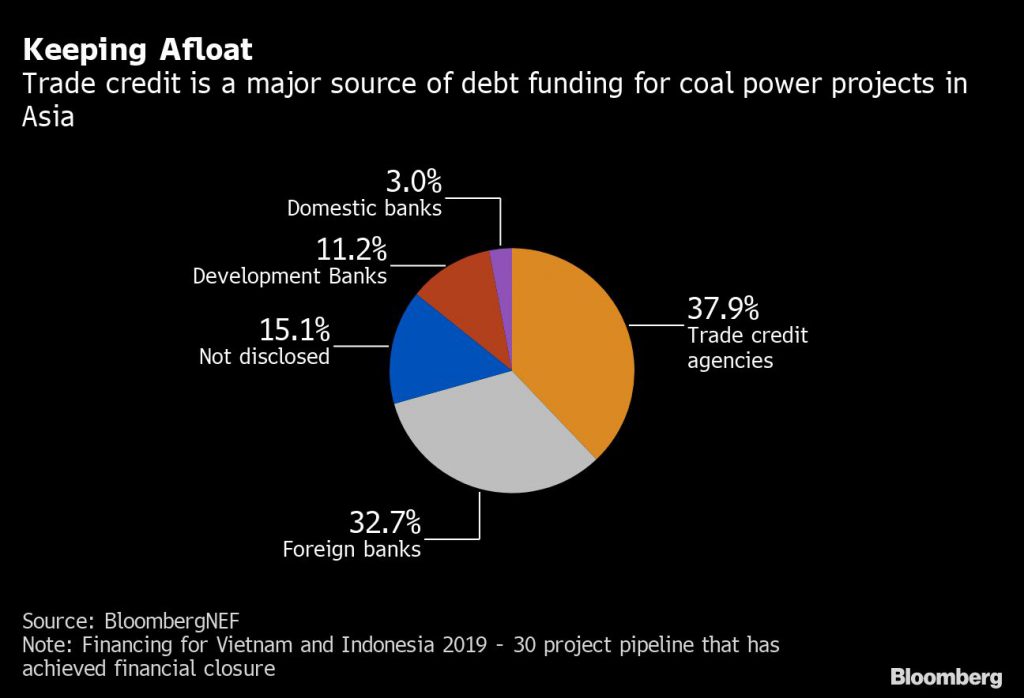

Chinese, Japanese and Korean state-owned export credit agencies are providing a “significant portion” of the money committed to building coal power stations in Southeast Asia, according to BloombergNEF.

Still, Japan’s biggest banks in particular are facing increasing pressure to withdraw from the coal business despite tightening their lending policies. MUFG said in May 2019 that it won’t provide financing for new coal-fired power generation projects, though it allows exceptions. Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group Inc. and Mizuho Financial Group Inc. have said they will only direct new funding to highly efficient plants. Mitsubishi Materials Corp. recently sold its 30-year-old stake in Australian thermal coal producer New Hope Corp.

The quandary for Japan was expressed last month by the head of JBIC, the state-run firm that’s been lending billions for coal-power projects. Tadashi Maeda said he prefers to invest in new technology to reduce emissions, rather than scrap financing altogether.

“Is it just enough to say we don’t do coal?,” Maeda told reporters. “If Japan doesn’t do it, other countries will.”

Asian banks aren’t the only life-line for coal miners. Private-equity firms are now a ‘’major source” of capital for coal deals, said Garold Spindler, chief executive officer of Australian coal miner Coronado Global Resources Inc.

When Rio Tinto Group sold its last Australian coal mine in 2018, the buyers were private equity firm EMR Capital Advisors Pty Ltd. and Indonesia’s PT Adaro Energy. Australia remains the world’s second-largest thermal coal exporter after Indonesia.

On a smaller scale, local activists tracking coal deals are starting to see unusual names pop up. When Wiggins Island Coal Export Terminal refinanced in 2018, lenders included distressed-debt funds Burlington Loan Management and Varde Investment Partners LP. One of the financiers of Whitehaven’s recent issue was Australian non-bank lender Metrics Credit Partners.

These new backers are increasingly drawn to coal projects in search of yield. Whitehaven refinanced its most recent loan at a rate of 200 basis points over the Australian swaps rate, or more than 40 points higher than the median rate for Aussie-denominated corporate loans of the same maturity, according to Bloomberg data. In an era of rock-bottom interest rates, that’s an attractive yield for a profitable company.

“There will continue to be financing at the right price,” said Dan Farley, Boston-based chief investment officer of Investment Solutions at State Street, who oversees $266 billion. The company didn’t disclose whether these holdings include coal.

However, as more banks retreat from funding thermal coal, operators around the world are bracing for higher finance costs – and increased risks that the projects will be scrapped. Last year, Polish generator Enea SA told shareholders borrowing costs would increase, and in February said it was suspending support for a new power station.

“There is clear proof that capital is fleeing the thermal coal power sector,” said Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies for Australasia at the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “Not all capital, not yet, but the tide is going out.”

The industry will face particular challenges for new projects, especially if coal prices continue to fall and as banks face more pressure to pull out. Billionaire Chris Hohn’s Children’s Investment Fund Foundation last week called on HSBC Holdings Plc and other U.K. banks to phase out coal financing. HSBC said it doesn’t support new thermal coal mines and hasn’t financed a coal-fired plant since 2018.

About half of the proposed 41 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity in Indonesia and Vietnam over the next decade haven’t secured funding, and plans by some banks in Japan, South Korea and Singapore to exit the sector increase the risk they never will, BloombergBNEF said in a report last month.

Global finance is on a “progressive exit” from the coal sector, IEEFA’s Buckley says. “But it will be a transition, not an abrupt overnight closure.”

(By Emily Cadman, with assistance from Matthew Burgess, Apple Lam and James Thornhill)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Andrés sorribes

Hydrogen may will be the king of energy in the world ( and even space) 20-30 years from now ?